Charismatic Leadership in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3782/28-dec-1989-on-the-presidents-202-address-33782.webp)

[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address

201 Motion of thanks [28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address SHRI DINESH GOSWAMI: Madam, I THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDE- also beg to lay on the Table a copy each (in PENDENT CHARGE) OF THE MINISTRY English and Hindi, ) of the following papers; OF WATER RESOURCES (SHRI MANOBHAI KOTADIA); Madam, I beg to I. (i) Thirty-first Annual Report and lay on the Table, under sub-section (1) Accounts of the Indian Law Institute, section 619A of tie Companies Act, 1956, a New Delhi, for the year 1987-88, to- copy each (in English and Hindi) of the gether with the Audit Report on the followng papers; — Accounts, (i) Twentieth Annual Report and Accounts (ii) Statement by Government accepting of the Water and Power. Consultancy the above Report. Services (India). Limited, New Delhi, for the year. 1988—89, together with the (iii) Statement giving reasons for the delay Auditor's Report on the Accounts and in laying the paper mentioned at (i) above. the comments of the Comptroller and [Placed in Library. See No. LT— 244/89 Auditor General of India thereon, for (i) to (iii)]. (ii) Review by Government on the II. A copy (in English and Hindi) of working of the Company. the Ministry of Law and Justice (Legisla [Placed in Library. See No. LT— tive Department) Notification S. O. No. 61/89]. 958(E), dated the 17th November, 1989, publishing the Conduct of Election; (Third Amendment) Rules, 1989, under section 169 of the Representation of the REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON People Act, 1951. -

Remembering Nehru and Non-Alig

Remembering Nehru and Non-Alignment in some Postcolonial Indian and French Texts Geetha Ganapathy-Doré To cite this version: Geetha Ganapathy-Doré. Remembering Nehru and Non-Alignment in some Postcolonial Indian and French Texts. International Journal of South Asian Studies, Pondicherry University, 2017, 10 (1), pp.5-11. hal-02119321 HAL Id: hal-02119321 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02119321 Submitted on 3 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain REMEMBERING NEHRU AND NON-ALIGNEMENT 1 Remembering Nehru and Non-Alignment in some Postcolonial Indian and French Texts Geetha Ganapathy-Doré Université Paris 13, Sorbonne Paris Cité Published in International Journal of South Asian Studies, Pondicherry University Vol 10, No1, January-June 2007, pp: 5-11. http://www.pondiuni.edu.in/sites/default/files/Journal_final_mode.pdf REMEMBERING NEHRU AND NON-ALIGNEMENT 2 Abstract For readers of Indian history, Nehru was the champion of anticolonialism, the architect of modern India, the ideologue of a mixed economy at the service of social justice, the Pandit from Kashmir, the purveyor of Panch Sheel, the disillusioned Prime Minister who had unwittingly initiated a dynastic democracy by relying on his daughter Indira after the death of his wife Kamala. -

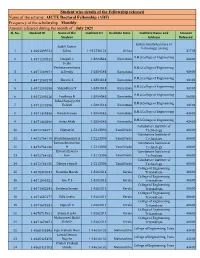

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution Across States

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 April 2013 Sponsored by Ministry of Panchayati Raj Government of India The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 V N Alok The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Foreword It is the twentieth anniversary of the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution, whereby Panchayats were given constitu- tional status.While the mandatory provisions of the Constitution regarding elections and reservations are adhered to in all States, the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats from the States has been highly uneven across States. To motivate States to devolve powers and responsibilities to Panchayats and put in place an accountability frame- work, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, ranks States and provides incentives under the Panchayat Empowerment and Accountability Scheme (PEAIS) in accordance with their performance as measured on a Devo- lution Index computed by an independent institution. The Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) has been conducting the study and constructing the index while continuously refining the same for the last four years. In addition to indices on the cumulative performance of States with respect to the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats, an index on their incremental performance,i.e. initiatives taken during the year, was introduced in the year 2010-11. Since then, States have been awarded for their recent exemplary initiatives in strengthening Panchayats. The Report on"Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States - Empirical Assessment 2012-13" further refines the Devolution Index by adding two more pillars of performance i.e. -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.2320 to Be Answered on 09.05.2016

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2320 TO BE ANSWERED ON 09.05.2016 MEMORIALS IN THE NAME OF FORMER PRIME MINISTERS 2320. SHRI C.R. PATIL Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government makes the nomenclature of the memorials in name of former Prime Ministers and other politically, socially or culturally renowned persons and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the State Government of Gujarat has requested the Ministry to pay Rs. One crore as compensation for acquiring Samadhi Land - Abhay Ghat to build a memorial in the name of Ex-PM Shri Morarji Desai and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the Government had constituted a Committee in past to develop a memorial on his Samadhi; and (d) the action taken by the Government to acquire the Sabarmati Ashram Gaushala Trust land to make memorial in the name of the said former Prime Minister? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR CIVIL AVIATION. DR. MAHESH SHARMA (a) Yes, Madam. The nomenclature of the memorials is given by the Government with the approval of Union Cabinet. For example: Samadhi of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is known as Shanti Vana, Samadhi of Mahatama Gandhi is known as Rajghat, Samadhi of late Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri is known as Vijay Ghat, Samadhi of Ch. Charan Singh is known as Kisan Ghat, Samadhi of Babu Jagjivan Ram is known as Samta Sthal, Samadhi of late Smt. Indira Gandhi is known as Shakti Sthal, Samadhi of Devi Lal is known as Sangharsh Sthal, Samadhi of late Shri Rajiv Gandhi is known as Vir Bhumi and so on. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Foartb Series Vol. XLII-No. 3 Wednesday, Jaly 29, 1970 Sravana 7, 1892 {Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES ( Eleventh Session) --- (Vol. XLII contains Nos. 1-10) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: .Re. 1.00 CONTENTS No. 3, Wednesday July 29, 1970/Sravana 7, 1892 (Saka). CoLUMNS Obituary Reference 1-7 Oral Answers to Questions- ·Starred Questions Nos. 61 7-27 Short Notice Question No. 1 28~33 Written Answers to Questions- Starred Questions Nos. 62 to 90 33-57 Unstarred Questions Nus. 401 to 40 ,407,408,410, 411, 413 to 460, 462 to 496 499 to 520, 5'<2 to 531 and 533 to 600. 57-216 Statement correcting answer to USQ No. 8777 dated the 6th May, 1970. 216--17 Calling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance- Anti-Indian Demonstrations in Saigon 217-240 Papers Laid on the Table 240--45 Direction by Speaker Under Rules of Procedure 245 Committee on Private Members' Bills and Resolutions- Sixty-fourth Report 245 Statement reo Strike 011 tile South Eastern and North Eastern Railways Shri Nanda 246 Business Advisory Committee- Fifty-first Report 246 Motion of No-Confidence in the Council of Ministers 246-380 Shri M. Muhammad Ismail 248-53 Dr. Govind Vas 233-58 Shri Sezhiyan 258-64 Shri S.A. Dange 265-76 Shri M.V. Krishnappa 276-81 Shri A.K. Gopalan ... 281-89 ·The sign +marked above the name of a Member indicates that the question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. (ii) COLUMNS Shri K. Hanumanthaiya 289-97 Shri Surendranath Dwivedy 297-306 Dr. -

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions for Class 3

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions For Class 3 Answer the following GK Questions on 10 Prime Ministers of India: Q1. Name the first Prime Minister of India who served office (15 August 1947 - 27 May 1964) until his death. a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Jawaharlal Nehru c) Rajendra Prasad d) Lal Bahadur Shastri Q2. _____________________ is the current Prime Minister of India (26 May 2014 – present). a) Narendra Modi b) Atal Bihari Vajpayee c) Manmohan Singh d) Ram Nath Kovind Q3. Who was the Prime Minister of India (9 June 1964 - 11 January 1966) until his death? a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Charan Singh c) Lal Bahadur Shastri d) Morarji Desai Q4. Who served as Prime Minister of India from 24 January 1966 - 24 March 1977? a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Gulzarilal Nanda c) Gopinath Bordoloi d) Indira Gandhi Q5. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 28 July 1979 - 14 January 1980. a) Jyoti Basu b) Morarji Desai c) Charan Singh d) V. V. Giri Q6. _______________________ served as the Prime Minister of India (21 April 1997 - 19 March 1998). a) Inder Kumar Gujral b) Charan Singh c) H. D. Deve Gowda d) Morarji Desai Q7. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 21 June 1991 - 16 May 1996. a) H. D. Deve Gowda b) P. V. Narasimha Rao c) Atal Bihari Vajpayee d) Chandra Shekhar Q8. ____________________________ was the Prime Minister of India (31 October 1984 - 2 December 1989). a) Chandra Shekhar b) Indira Gandhi c) Rajiv Gandhi d) P. V. Narasimha Rao Q9. -

1 Ounding Father Who Galvanized, Inspired, Scandalized and Shaped

ounding Father who galvanized, inspired, scandalized and shaped the newborn nation. In the first full-length biography of Alexander Hamilton in decades, Ron Chernow tells the riveting story of a man who overcame all odds to shape, inspire and scandalize the newborn America. According to historian Joseph Ellis, Alexander Hamilton is “a robust full-length portrait, in my view the best ever 1 written, of the most brilliant, charismatic and dangerous founder of them all.” Chernow’s biography is not just a portrait of Hamilton, but the story of America’s birth seen through its most central figure. At a critical time to look back to our roots, Alexander Hamilton will remind readers of the purpose of our institutions and our heritage as Americans. It was the British victory at the Battle of El Alamein in November 1942 that inspired one of Winston Churchill's most famous aphorisms: 'This is not the end, it is not even the beginning of the end, but it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning'. And yet the significance of this episode remains unrecognised. In this thrilling historical account, Jonathan Dimbleby describes the political and 2 strategic realities that lay behind the battle, charting the nail-biting months that led to the victory at El Alamein in November 1942. It is a story of high drama, played out both in the war capitals of London, Washington, Berlin, Rome and Moscow, and at the front in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Morrocco and Algeria and in the command posts and foxholes in the desert. In this remarkable book, which is partly a memoir and partly an exploration of the various deliberate and inadvertent acts that have contributed to the othering of the 180 million Muslims in India, Saeed Naqvi looks at how the divisions between Muslims and Hindus began in the modern era. -

Definitieve Versie Scriptie.Docx

‘We must hunt with the hounds and run with the hare!’ An Indian Parsi temple in Hyderabad. (http://whotalking.com/flickr/Parsi , consulted on 02-05-2012) The changing identity of Parsis in India and abroad. Research Master Thesis History. Specialisation: Migration and Global Interdependence. E.W. (Liesbeth) Rosen Jacobson, s0729280. Supervisor: Mevr. Prof. Dr. M.L.J.C. Schrover Leiden University, 15-06-2012. 1 2 Table of contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1. Main question 4 1.2. Theoretical framework 10 1.3. Historiography 14 1.4. Material and method 15 2. The Parsis of India 21 2.1. The history of the Parsis in India 21 2.2. The Parsi diaspora in the UK, the US and worldwide 25 2.3. The changing meaning of being Parsi: religion and community features 31 3. Analysis of newspaper and magazine articles 36 3.1. Discourse, news and identities 36 3.2. Before and after Independence 37 3.3. Ascribed and self-defined identity 41 3.4. Diaspora versus homeland India after Independence 48 3.5. The United States versus the United Kingdom and the New York Times 53 3.6. Conclusion 59 4. Literary analysis of the books 62 4.1. Introduction and summaries of the novels 62 4.2. The Westernization and Britishness of the Parsis 68 4.3. Minority Discourse 73 4.4. Religion and community features 74 4.5. Magic 79 4.6. Conclusion. 81 5. Conclusion 84 6. Literature 89 7. Websites 92 Appendix I: Basic tables used for the discourse analysis. 93 3 1. -

Reflections on the Transfer of Power and Jawaharlal Nehru Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma KG PC GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO FRS

Reflections on the Transfer of Power and Jawaharlal Nehru Admiral of the Fleet The Earl Mountbatten of Burma KG PC GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO FRS Trinity College, University of Cambridge - 14th November 1968. This is the second Nehru Memorial Lecture. At the suggestion of the former President of India the first was given, most appropriately, by the Master of Jawaharlal Nehru’s old College, Trinity. Lord Butler was born in India, the son of a most distinguished member of the Indian Civil Service, who was one of the most successful Governors. As Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India he was one of those responsible for the truly remarkable 1935 Government of India Act, the Act which I used to speed up the transfer of power. Thus Lord Butler’ ties with India are strong and it not surprising that he gave such an excellent lecture, which has set such a high standard. He dealt faithfully with the life and career of Jawaharlal Nehru from his birth seventy-nine years ago this very day up to 1947. My fellow trustees of the Nehru Memorial Trust have persuaded me to deliver the second lecture. This seemed the occasion to give a connected narrative of the events leading up to the transfer of power in August 1947, and indeed to continue up to June 1948, when I ceased to be India’s first Constitutional Governor-General. It would have been nice to show how Nehru fitted into these events, but in the time available such a task soon proved to be out of the question, so I have deliberately confined myself to recalling the highlights of my Viceroyalty and to assessing Nehru’s relations to the principal men and events at the time, and to general reminiscences of him to illustrate the part he played up to the actual transfer of power.