Manmohan Singh 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

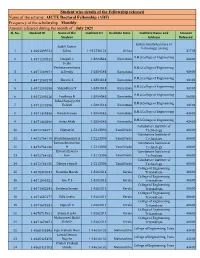

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.2320 to Be Answered on 09.05.2016

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2320 TO BE ANSWERED ON 09.05.2016 MEMORIALS IN THE NAME OF FORMER PRIME MINISTERS 2320. SHRI C.R. PATIL Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government makes the nomenclature of the memorials in name of former Prime Ministers and other politically, socially or culturally renowned persons and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the State Government of Gujarat has requested the Ministry to pay Rs. One crore as compensation for acquiring Samadhi Land - Abhay Ghat to build a memorial in the name of Ex-PM Shri Morarji Desai and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the Government had constituted a Committee in past to develop a memorial on his Samadhi; and (d) the action taken by the Government to acquire the Sabarmati Ashram Gaushala Trust land to make memorial in the name of the said former Prime Minister? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR CIVIL AVIATION. DR. MAHESH SHARMA (a) Yes, Madam. The nomenclature of the memorials is given by the Government with the approval of Union Cabinet. For example: Samadhi of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is known as Shanti Vana, Samadhi of Mahatama Gandhi is known as Rajghat, Samadhi of late Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri is known as Vijay Ghat, Samadhi of Ch. Charan Singh is known as Kisan Ghat, Samadhi of Babu Jagjivan Ram is known as Samta Sthal, Samadhi of late Smt. Indira Gandhi is known as Shakti Sthal, Samadhi of Devi Lal is known as Sangharsh Sthal, Samadhi of late Shri Rajiv Gandhi is known as Vir Bhumi and so on. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

Evidence from India's Maoist Rebellion

Descriptive Representation and Conflict Reduction: Evidence from India’s Maoist Rebellion* Aidan Milliff † & Drew Stommes ‡ April 19, 2021 Abstract Can greater inclusion in democracy for historicallydisadvantaged groups reduce rebel vio lence? Democracybuilding is a common tool in counterinsurgencies and postconflict states, yet existing scholarship has faced obstacles in measuring the independent effect of democratic reforms. We evaluate whether quotas for Scheduled Tribes in local councils reduced rebel vi olence in Chhattisgarh, an Indian state featuring highintensity Maoist insurgent activity. We employ a geographic regression discontinuity design to study the effects of identical quotas implemented in Chhattisgarh, finding that reservations reduced Maoist violence in the state. Exploratory analyses of mechanisms suggest that reservations reduced violence by bringing lo cal elected officials closer to state security forces, providing a windfall of valuable information to counterinsurgents. Our study shows that institutional engineering and inclusive representa tive democracy, in particular, can shape the trajectory of insurgent violence. Word Count: 9,086 (incl. references) *We are grateful to Peter Aronow, Erica Chenoweth, Fotini Christia, Andrew Halterman, Elizabeth Nugent, Rohini Pande, Roger Petersen, Fredrik Sävje, Steven Wilkinson, and Elisabeth Wood for insightful comments on previous drafts of this article. We also thank audiences at the HarvardMITTuftsYale Political Violence Conference (2020), MIT Security Studies -

Finland Bilateral Relations Finland and India Have Traditionally Enjoyed

March 2021 Ministry of External Affairs **** India – Finland Bilateral Relations Finland and India have traditionally enjoyed warm and friendly relations. In recent years, bilateral relations have acquired diversity with collaboration in research, innovation, and investments by both sides. The Indian community in Finland is vibrant and well-placed. Indian culture and yoga are very popular in Finland. 2019 marked 70 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries. High-level visits - Prime Ministers • Prime Minister Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru Finland in 1957 • Prime Minister Smt. Indira Gandhi in 1983. • Prime Minister Pt. Manmohan Singh in 2006. • Mr. Vieno Johannes Sukselainen in 1960 - First Prime Minister of Finland • Prime Minister Mr. Kalevi Sorsa in 1984. • Prime Minister Mr. Matti Vanhanen visited India in March 2006, February 2008 and February 2010 (last two occasions to attend Delhi Sustainable Development Summit). • Prime Minister Mr. Juha Sipilä: Feb 2016 (for Make in India week) Presidential Visits • President of Finland Mr. Urho Kekkonen in 1965 • President Mr. Mauno Koivisto in 1987 • President Mr. Martti Ahtisaari in 1996. • President Mrs. Tarja Halonen in January 2007, February 2009 and February 2012 to attend the Delhi Sustainable Development Summit. • President Shri V.V. Giri in 1971 • President Shri R. Venkataraman in 1988. • President Shri Pranab Mukherjee: October 2014 President Shri Pranab Mukherjee, paid a State Visit to Finland on 14-16 October 2014 accompanied by Minister of State for Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises, four Members of Parliament, Officials, academicians and a business delegation. Agreements for cooperation in New and Renewable Energy, Biotechnology, Civil Nuclear Research, Meteorology, Healthcare and Education were signed during the visit. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

H.E. Mrs. Sushma Swaraj, Minister of External Affairs, India H.E. Dr. Manmohan Singh, Former Prime Minister of India Distinguish

Address by H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India, at the Reception to commemorate the Imperial Succession in Japan, on 1 May 2019 H.E. Mrs. Sushma Swaraj, Minister of External Affairs, India H.E. Dr. Manmohan Singh, Former Prime Minister of India Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, (Opening) Yesterday, on 30th April, His Majesty the Emperor Akihito abdicated from the Throne after his reign of 30 years, marking the end of the Heisei era. Today, His Majesty the Emperor Naruhito acceded to the Throne. A new era titled “Reiwa” began under the new Emperor. This historic succession to the Imperial Throne from a living Emperor is the first such instance taking place in approximately 200 years. Japan is now overwhelmed with gratitude for Their Majesties the Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko, who have always wished for the happiness of the 1 Japanese people and peace in the world. At the same time, the Japanese people are brimming with the joy of stepping into a new era under Their Majesties the Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako. I am honoured to host this reception tonight to celebrate this momentous day for Japan with our friends who have been contributing enormously towards strengthening the Japan-India relationship in various areas. I am delighted that you are joining us this evening. (Japan-India relationship in Heisei) During the Heisei era, the Japan-India relationship has deepened and expanded to an unprecedented scale. An enduring symbol of this strong bilateral relationship is Their Majesties’ visit to India in 2013. -

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions for Class 3

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions For Class 3 Answer the following GK Questions on 10 Prime Ministers of India: Q1. Name the first Prime Minister of India who served office (15 August 1947 - 27 May 1964) until his death. a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Jawaharlal Nehru c) Rajendra Prasad d) Lal Bahadur Shastri Q2. _____________________ is the current Prime Minister of India (26 May 2014 – present). a) Narendra Modi b) Atal Bihari Vajpayee c) Manmohan Singh d) Ram Nath Kovind Q3. Who was the Prime Minister of India (9 June 1964 - 11 January 1966) until his death? a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Charan Singh c) Lal Bahadur Shastri d) Morarji Desai Q4. Who served as Prime Minister of India from 24 January 1966 - 24 March 1977? a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Gulzarilal Nanda c) Gopinath Bordoloi d) Indira Gandhi Q5. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 28 July 1979 - 14 January 1980. a) Jyoti Basu b) Morarji Desai c) Charan Singh d) V. V. Giri Q6. _______________________ served as the Prime Minister of India (21 April 1997 - 19 March 1998). a) Inder Kumar Gujral b) Charan Singh c) H. D. Deve Gowda d) Morarji Desai Q7. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 21 June 1991 - 16 May 1996. a) H. D. Deve Gowda b) P. V. Narasimha Rao c) Atal Bihari Vajpayee d) Chandra Shekhar Q8. ____________________________ was the Prime Minister of India (31 October 1984 - 2 December 1989). a) Chandra Shekhar b) Indira Gandhi c) Rajiv Gandhi d) P. V. Narasimha Rao Q9. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Special Economic Zones in India – an Introduction

ASIEN 106 (Januar 2008), S. 60-80 Special Economic Zones in India – An Introduction Jona Aravind Dohrmann Summary This introductory article describes the salient features of the Indian embodiment of the model Chinese SEZ, how it evolved and what the various steps are in making an Indian SEZ function: from submitting an application and receiving a Letter of Approval for the establishment of an SEZ to getting the authorised operations and particular units sanctioned. The SEZs are tax-free enclaves for investors from India and abroad. As the Prime Minister of India, Dr. Manmohan Singh, said: “SEZs are here to stay”. The Indian government and the state governments are now finding that it is not enough to promulgate modern laws luring foreign direct investment into India, but that they also have to provide for the concerns and the livelihoods of those affected by the establishment of SEZs. “The current promotion of SEZs is unjust and would act as a trigger for massive social unrest, which may even take the form of armed struggle.” Vishwanath Pratap Singh, former Prime of India, in: Frontline, 20 October 2006 1 Introduction Lately, India, or at least its economic growth, seems to be on everybody’s agenda the world over. Its economic development particularly fires the imagination of In- dian and foreign investors. This has led to books being published with titles like “Global Power India” or slogans like “China was yesterday, India is today”. Many institutions such as the Indo-German Chamber of Commerce or various consulting companies in Germany sing the Indian tune and recommend doing business in the subcontinent. -

DR. MANMOHAN SINGH): Madam, Speaker, I Returned Earlier Today from Visits to France and Egypt

> Title : Statement regarding Prime Minister's recent visits to Italy, France and Egypt. THE PRIME MINISTER (DR. MANMOHAN SINGH): Madam, Speaker, I returned earlier today from visits to France and Egypt. Before that I had visited Italy for the G-8/G-5 Summit meetings. Meetings of the G-8 and G-5 countries have become an annual feature. The agenda for this year's meetings was wide ranging, but the main focus was on the on-going global economic and financial slowdown. The developing countries have been the most affected by the global financial and economic crisis. I stressed the importance of a concerted and well-coordinated global response to address systemic failures and to stimulate the real economy. There is need to maintain adequate flow of finance to the developing countries and to keep markets open by resisting protectionist pressures. As a responsible member of the international community, I conveyed to the G-8 and G-5 countries that we recognize our obligation to preserve and protect our environment but climate change cannot be addressed by perpetuating the poverty of the developing countries. I presented India's Action Plan on Climate Change and the eight National Missions which we have set up in this regard. We are willing to do more provided there are credible arrangements to provide both additional financial support as well as technological transfers from developed to developing countries. India's participation as guest of honour at the French National Day was an honour and a matter of pride for us all. I wish to share with the hon.