Integrating Local Languages and Cultures Into the Education System of French Guiana a Discussion of Current Programs and Initiatives*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Creole

Comparative perspectives on the origins, development and structure of Amazonian (Karipúna) French Creole Jo-Anne S. Ferreira UWI, St. Augustine/SIL International Mervyn C. Alleyne UWI, Mona/UPR, Río Piedras Together known as Kheuól, Karipúna French Creole (KFC) and Galibi-Marwono French Creole (GMFC) are two varieties of Amazonian French Creole (AFC) spoken in the Uaçá area of northern Amapá in Brazil. Th ey are socio-historically and linguistically connected with and considered to be varieties of Guianese French Creole (GFC). Th is paper focuses on the external history of the Brazilian varieties, and compares a selection of linguistic forms across AFC with those of GFC and Antillean varieties, including nasalised vowels, the personal pronouns and the verbal markers. St. Lucian was chosen as representative of the Antillean French creoles of the South-Eastern Caribbean, including Martinique and Trinidad, whose populations have had a history of contact with those of northern Brazil since the sixteenth century. Data have been collected from both fi eld research and archival research into secondary sources. Introduction Th is study focuses on a group of languages/dialects which are spoken in Brazil, French Guiana and the Lesser Antilles, and to a lesser extent on others spoken in other parts of the Americas (as well as in the Indian Ocean). Th is linguistic group is variously referred to as Creole French, French Creole, French-lexicon Creole, French-lexifi er Creole, French Creole languages/dialects, Haitian/Martiniquan/St. Lucian (etc.) Cre- ole, and more recently by the adjective of the name of the country, particularly in the case of the Haiti (cf. -

French Studies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository 1 Prepared for: The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, Volume 71 (survey year 2009; to appear in 2011). [TT]French Studies [TT]Language and Linguistics [A]By Paul Rowlett, University of Salford [H2]1. General The proceedings of the first Congrès mondial de linguistique française, held in Paris in July 2008, have been published online at http://www.linguistiquefrancaise.org/index.php?option+ toc&url=/articles/cmlf/abs/2008/01/contents/contents.html/. The 187 contributions are divided into thematic sections many of which will be of interest to readers. FM, special issue, *‘Tendances actuelles de la linguistique française’, 2008, 140 pp., includes contributions by C. Marchello-Nizia, F. Gadet, C. Blanche-Benveniste, and others. *Morin Vol. contains a broad selection of fifteen contributions by J. Durand, F. Gadet, R. S. Kayne, B. Laks, A. Lodge, and others, covering the phonology and morphosyntax of standard and regional varieties (including North American), from diachronic, synchronic, and sociolinguistic perspectives. [H2]2. History of the Language *Sociolinguistique historique du domaine gallo-roman: enjeux et méthodologies, ed. D. Aquino- Weber et al., Oxford, Lang, xiv + 335 pp., includes an introduction and 14 other contributions. S. Auroux, ‘Instrumentos lingüísticos y políticas lingüísticas: la construcción del francés’, Revista argentina de historiografía lingüística, 1:137–49, focuses on the policies and tools which underlay the ‘construction’ of Fr. and concludes that the historical milestones are more political and literary than linguistic, revolving around efforts to impose the monarch’s variety as standard and the ‘grammatization’ of Fr. -

French Guianese Creole Its Emergence from Contact

journal of language contact 8 (2015) 36-69 brill.com/jlc French Guianese Creole Its Emergence from Contact William Jennings University of Waikato [email protected] Stefan Pfänder FRIAS and University of Freiburg [email protected] Abstract This article hypothesizes that French Guianese Creole (fgc) had a markedly different formative period compared to other French lexifier creoles, a linguistically diverse slave population with a strong Bantu component and, in the French Caribbean, much lower or no Arawak and Portuguese linguistic influence.The historical and linguistic description of the early years of fgc shows, though, that the founder population of fgc was dominated numerically and socially by speakers of Gbe languages, and had almost no speakers of Bantu languages. Furthermore, speakers of Arawak pidgin and Portuguese were both present when the colony began in Cayenne. Keywords French Guianese Creole – Martinique Creole – Arawak – tense and aspect – founder principle 1 Introduction French Guianese Creole (hereafter fgc) emerged in the South American col- ony of Cayenne in the late 1600s. The society that created the language was superficially similar to other Caribbean societies where lexically-French cre- oles arose. It consisted of slaves of African origin working on sugar plantations for a minority francophone colonial population. However, from the beginning © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2015 | doi 10.1163/19552629-00801003Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 09:17:10PM via free access <UN> French Guianese Creole 37 fgc was quite distinct from Lesser Antillean Creole. It was “less ridiculous than that of the Islands” according to a scientist who lived in Cayenne in the 1720s (Barrère 1743: 40). -

Lexicography in the French Caribbean: an Assessment of Future Opportunities

LEXICOGRAPHY IN GLOBAL CONTEXTS 619 Lexicography in the French Caribbean: An Assessment of Future Opportunities Jason F. Siegel The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus E-mail: [email protected] Abstract While lexicography in the Hispanophone Caribbean has flourished, and to a lesser extent in the territories of the Caribbean whose official language is English, dictionaries of the French-official Caribbean (except Haiti) have been quite limited. But for the rest of the French-official Caribbean, there remains much work to do. In this paper, I assess the state of lexicography in the French-official Caribbean, as well as the possibilities for fu- ture work. There are six principal areas of lexicographic documentation to be developed. The first, most urgent task is the documentation of the endangered St Barth French. The next priority is multilingual lexicography for the Caribbean region. The third priority is multilingual lexicography of French Guiana, home to endangered Amerindian, Creole and immigrant languages. Fourth, there is a largely pristine area of lexicographic work for the English varieties of the French Caribbean. The fifth area of work to be developed is monolingual lexicog- raphy of French-based Creoles. Lastly, there is exploratory work to be done on the signed language varieties of the French-official Caribbean. The paper concludes with a discussion of the role that the Richard and Jeannette Allsopp Centre for Caribbean Lexicography can play in the development of these areas. Keywords: minority languages, bilingual lexicography, French Caribbean 1 Introduction Overseas French (le français d’outre-mer) is a fairly important topic in French linguistics. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Code-Switching Between Structural and Sociolinguistic Perspectives Linguae & Litterae

Code-switching Between Structural and Sociolinguistic Perspectives linguae & litterae Publications of the School of Language & Literature Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies Edited by Peter Auer, Gesa von Essen and Frick Werner Editorial Board Michel Espagne (Paris), Marino Freschi (Rom), Ekkehard König (Berlin), Michael Lackner (Erlangen-Nürnberg), Per Linell (Linköping), Angelika Linke (Zürich), Christine Maillard (Strasbourg), Lorenza Mondada (Basel), Pieter Muysken (Nijmegen), Wolfgang Raible (Freiburg), Monika Schmitz-Emans (Bochum) Volume 43 Code-switching Between Structural and Sociolinguistic Perspectives Edited by Gerald Stell and Kofi Yakpo DE GRUYTER ISBN 978-3-11-034354-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-034687-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-038394-2 ISSN 1869-7054 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston Typesetting: Meta Systems Publishing & Printservices GmbH, Wustermark Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Acknowledgements VII Gerald Stell, Kofi Yakpo Elusive or self-evident? Looking for common ground in approaches to code-switching 1 Part 1: Code-switching -

Aruba Abstracts 2014

ABSTRACTS SCL/SPCL/ACBLPE CONFERENCE 2014 Abstracts of Papers to be presented at the 20 th Biennial Conference of the Society for Caribbean Linguistics, being held in conjunction with the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL) and the Associação de Crioulos de Base Lexical Portuguesa e Espanhola (ACBLPE) at th e Holiday Inn Resort, Aruba from 5 to 8 August 2014. ---◊◊-◊◊◊◊◊◊---- ALLEYNE, Mervyn C. (Keynote(Keynote)))) The University of the West Indies, MonaMona////Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras (Retired) A Reformist Approach to the "Creole" Concept The wider perspective of this essay is The Naming of the “New World” (sic), the appropriation by the new rulers and classifiers of the prerogative of “naming” and thereby of setting the semantic structures and the significant symbols in their interests and favour. Examples such as mulatto and the use of colour terms abound to refer to the different ethnic groups, highly positive in the case of “whit e” and extremely negative in all the other cases: black, red, yellow. The naming of the new languages is also a very instructive example. This essay interrogates the meanings and values of the names given to the languages which emerged in the New World (si c) which are all misleading and offensive and should be rejected in the same way that other terms such as “Coolie”, nigger”, “black”, “mulatto”, personal names and street names, etc. have been rejected in the cleaning -up sweep of post- colonial reform. Thi s essay concentrates on “creole”, as in “Trinidadians speak a creole”; it also deals with two other more offensive terms/concepts: “patois” and “pidgin”. -

Conference Abstracts

ABSTRACTS SCL/SPCL/ACBLPE CONFERENCE 2014 Abstracts of Papers presented at the 20th Biennial Conference of the Society for Caribbean Linguistics, held in conjunction with the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL) and the Associação de Crioulos de Base Lexical Portuguesa e Espanhola (ACBLPE) at the Holiday Inn Resort, Aruba, from 5 to 8 August 2014. -◊◊- ALLEYNE, Mervyn C. (Keynote) The University of the West Indies, Mona/Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras (Retired) A Reformist Approach to the "Creole" Concept The wider perspective of this essay is The Naming of the “New World” (sic), the appropriation by the new rulers and classifiers of the prerogative of “naming” and thereby of setting the semantic structures and the significant symbols in their interests and favour. Examples such as mulatto and the use of colour terms abound to refer to the different ethnic groups, highly positive in the case of “white” and extremely negative in all the other cases: black, red, yellow. The naming of the new languages is also a very instructive example. This essay interrogates the meanings and values of the names given to the languages which emerged in the New World (sic) which are all misleading and offensive and should be rejected in the same way that other terms such as “Coolie”, nigger”, “black”, “mulatto”, personal names and street names, etc. have been rejected in the cleaning-up sweep of post- colonial reform. This essay concentrates on “creole”, as in “Trinidadians speak a creole”; it also deals with two other more offensive terms/concepts: “patois” and “pidgin”. “Creole” has prospered in post-colonial discourse, and in particular in post-modern thought. -

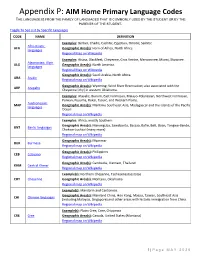

Appendix P: AIM Home Primary Language Codes the LANGUAGE IS from the FAMILY of LANGUAGES THAT IS COMMONLY USED by the STUDENT OR by the PARENTS of the STUDENT

Appendix P: AIM Home Primary Language Codes THE LANGUAGE IS FROM THE FAMILY OF LANGUAGES THAT IS COMMONLY USED BY THE STUDENT OR BY THE PARENTS OF THE STUDENT. Toggle To See List by Specific Languages CODE NAME DEFINITION Examples: Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian, Omotic, Semitic. Afro-Asiatic AFA Geographic Area(s): Horn of Africa, North Africa. languages Regional Map on Wikipedia Examples: Atsina, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Gros Ventre, Menominee, Miami, Shawnee. Algonquian; Algic ALG Geographic Area(s): North America. languages Regional Map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Saudi Arabia, North Africa. Arabic ARA Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Wyoming: Wind River Reservation; also associated with the ARP Arapaho Cheyenne [chy] in western Oklahoma. Examples: Atayalic, Bunum, East Formosan, Malayo-Polynesian, Northwest Formosan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Tsouic, and Western Plains. Austronesian MAP Geographic Area(s): Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar and the islands of the Pacific languages Ocean Regional map on Wikipedia Examples: Africa, mostly Southern Geographic Area(s): Manenguba, Sawabantu, Bassaa, Bafie, Beti, Boan, Tongwe-Bende, BNT Bantu languages Chokwe-Luchazi (many more) Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Myanmar BUR Burmese Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Philippines CEB Cebuano Regional map on Wikipedia Geographic Area(s): Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand KHM Central Khmer Regional map on Wikipedia Example(s): Northern Cheyenne, Tsehesenestsestotse CHY Cheyenne Geographic Area(s): Montana, -

Copyrighted Material

Index AAE see African American agentive, 96, 107–8 aspirations, 53 English “aks,” 82, 87 asymmetrical bilingualism, 148 see aboriginals, 89, 104 Alabama, 173, 185 also multilingualism; power academic language, 2, 93 Alatis, James E., 214 Atlantic Canada, 204 Acadian French, 161 Albanian, 162 attention to speech, 121–2 see also accents, 16, 28, 35, 174, 176 see Al‐Wer, E., 107, 211 style also dialect Alzheimer’s disease, 77 attitudes and ideologies, 171–87 Disney films, 181 amelioration (semantics), 66 see also language diversity accommodation, 94 see also American Civil War, 42 investigations of attitudes, interlocutors American Midwest, 73–4 172–6 acrolect, 165, 166 see also mesolect American Revolution (1776–83), language beliefs (myths, actuation problem, 67 30, 38 ideologies), 177–80 Adams, Michael, 91 American Speech, 50 maps, 172–3 address forms see forms of address Amsterdam, 107 reading and responding, 180–1 adjacency pair, 136 Angles, 28 audience design, 122–4 see also adolescence, 76–7, 80, 204 Anglicans, 39 style shift African American English (AAE), Annual Review of Anthropology, auditors, degrees of closeness, 18, 38, 42, 44, 72, 82, 83, 186 122–3 86–9, 91–3, 117, 139, 173, anthropology, 176 see also Austin, J.L., 135 174, 176, 177, 179, 181, 182, ethnography Australia, 31, 34, 181 206 see also ethnicity anti‐languages, 183 Austria, 153 derogatory names, 88,COPYRIGHTED 91 Apache, 137 MATERIALauthenticity, 160 African slaves, 82, 86, 88 Appalachia, 28, 42 autism, 58 after perfect, 36 apparent time hypothesis, 64–5, age, 75–7 see also schools; time 192 baby boomers, 75 age grading, 69, 192 applied linguistics, 4, 5 Bahasa Indonesia, 197 apparent time hypothesis, 65 Arabic, 107, 149, 175 Bailey, Benjamin H., 139 lifespan changes, 69–70, 75–7 argot, 129 see also slang Bailey, Guy, 69 style, 75, 76 Arvanitika, 172 Bajan, 164 see also Barbados What Is Sociolinguistics?, Second Edition. -

French Guiana As a Case Study for Cross-Cultural Ethnobotanical Hybridization M.-A

Tareau et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2020) 16:54 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00404-1 RESEARCH Open Access Phytotherapies in motion: French Guiana as a case study for cross-cultural ethnobotanical hybridization M.-A. Tareau1* , A. Bonnefond2, M. Palisse1 and G. Odonne1 Abstract Background: French Guiana is characterized by a very multicultural population, made up of formerly settled groups (Amerindians, Maroons, Creoles) and more recent migrants (mostly from Latin America and the Caribbean). It is the ideal place to try to understand the influence of intercultural exchanges on the composition of medicinal floras and the evolution of phytotherapies under the effect of cross-culturalism. Methods: A combination of qualitative and quantitative methods was used. Semi-directive interviews were conducted in 12 localities of French Guiana’s coast between January 2016 and June 2017, and the responses to all closed questions collected during the survey were computerized in an Excel spreadsheet to facilitate quantitative processing. Herbarium vouchers were collected and deposited at the Cayenne Herbarium to determine Linnaean names of medicinal species mentioned by the interviewees. A list of indicator species for each cultural group considered was adapted from community ecology to this ethnobiological context, according to the Dufrêne- Legendre model, via the “labdsv” package and the “indval” function, after performing a redundancy analysis (RDA). Results: A total of 205 people, belonging to 15 distinct cultural groups, were interviewed using semi-structured questionnaires. A total of 356 species (for 106 botanical families) were cited. We observed that pantropical and edible species hold a special place in these pharmacopeias. -

Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina M Migge

Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina M Migge To cite this version: Bettina M Migge. Caribbean, South and Central America. The Routledge Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Language, Miriam Meyerhoff & Umberto Ansaldo (eds.), 150-178. Malden, MA: Routledge., 2020. hal-03085559 HAL Id: hal-03085559 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03085559 Submitted on 21 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina Migge 1. INTRODUCTION The Caribbean, South and Central America are a vast region that has been significantly affected by European colonial expansion. The experience was by no means homogeneous across the region. While the latter two regions were mainly dominated and influenced by Spain and to a lesser extent Portugal (South America), the Caribbean and the Guiana region of South America were subject to expansionist activities from a number of European nations (Denmark, England, France, Netherlands, Spain). Official political dependency on Europe also lasted much longer and still continues in some cases in the Caribbean and the Guiana region while it ended for the most part in the early 19th century in the other two regions.