Conference Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFLECTIONS on LIFE: CREOLES, the INTERSECTION of MANY PEOPLES Growing up As Little People, My Siblings and I, As Well As Our Re

REFLECTIONS ON LIFE: CREOLES, THE INTERSECTION OF MANY PEOPLES Growing up as little people, my siblings and I, as well as our relatives, friends and neighbors, sponged up everything around us, unaware that a Creole culture was the atmosphere and environment that we lived, breathed and ingested constantly. It was our father who spoke Cajun, the old French from Canada, and our mother who spoke Creole, the oft-fractured French so dear to all who are part of that culture. A many-splendored culture, it has purloined gems of all kinds from other cultures, in the process of creating its own distinctive jewels unlike any in the world. From rich goodness and talent in every walk of life, we are a flavorful gumbo appetizing to all. With an incredible length and breadth, Creoles span all the color spectrum from deep ebony to dark chocolate to milk chocolate to teasing tan to the ambiguous ivory-complected to sepia to the reddish briqué to high yellow to white. Technically, black is not a color, for it is the absence of visible light. Neither is white a color, for it contains all the wavelengths of visible light. So what is this black/white fuss all about? In any case, most of us are of Afro- Euro-Asian (First American) extraction – quite a bit in addition to what we usually call African American. Seizing upon these broad-based commonalities, confessed Creole Georgina Dhillon from the Seychelles, who later moved to London, had a dream to unite the formidable concentrations of Creoles: Antillean Creole, spoken among 100,000 in Dominica, “The nature isle of the Caribbean”; Antillean Creole, among 100,000 in Grenada; Antillean Creole, among 422,496 in Guadeloupe; French Guiana Creole and Haitian Creole, among 157,277 in French Guiana; Haitian Creole, among 7,000,000 in Haiti; Antillean Creole, among 381,441 in Martinique; Mauritian Creole, among 1,100,000 in Mauritius; Réunion Creole, among 707,758 in Réunion; Antillean Creole, among 150,000 in St. -

French Creole

Comparative perspectives on the origins, development and structure of Amazonian (Karipúna) French Creole Jo-Anne S. Ferreira UWI, St. Augustine/SIL International Mervyn C. Alleyne UWI, Mona/UPR, Río Piedras Together known as Kheuól, Karipúna French Creole (KFC) and Galibi-Marwono French Creole (GMFC) are two varieties of Amazonian French Creole (AFC) spoken in the Uaçá area of northern Amapá in Brazil. Th ey are socio-historically and linguistically connected with and considered to be varieties of Guianese French Creole (GFC). Th is paper focuses on the external history of the Brazilian varieties, and compares a selection of linguistic forms across AFC with those of GFC and Antillean varieties, including nasalised vowels, the personal pronouns and the verbal markers. St. Lucian was chosen as representative of the Antillean French creoles of the South-Eastern Caribbean, including Martinique and Trinidad, whose populations have had a history of contact with those of northern Brazil since the sixteenth century. Data have been collected from both fi eld research and archival research into secondary sources. Introduction Th is study focuses on a group of languages/dialects which are spoken in Brazil, French Guiana and the Lesser Antilles, and to a lesser extent on others spoken in other parts of the Americas (as well as in the Indian Ocean). Th is linguistic group is variously referred to as Creole French, French Creole, French-lexicon Creole, French-lexifi er Creole, French Creole languages/dialects, Haitian/Martiniquan/St. Lucian (etc.) Cre- ole, and more recently by the adjective of the name of the country, particularly in the case of the Haiti (cf. -

![A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0716/a-sociophonetic-study-of-the-metropolitan-french-r-linguistic-factors-determining-rhotic-variation-a-senior-honors-thesis-970716.webp)

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Sarah Elyse Little The Ohio State University June 2012 Project Advisor: Professor Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza, Department of Spanish and Portuguese ii ABSTRACT Rhotic consonants are subject to much variation in their production cross-linguistically. The Romance languages provide an excellent example of rhotic variation not only across but also within languages. This study explores rhotic production in French based on acoustic analysis and considerations of different conditioning factors for such variation. Focusing on trills, previous cross-linguistic studies have shown that these rhotic sounds are oftentimes weakened to fricative or approximant realizations. Furthermore, their voicing can also be subject to variation from voiced to voiceless. In line with these observations, descriptions of French show that its uvular rhotic, traditionally a uvular trill, can display all of these realizations across the different dialects. Focusing on Metropolitan French, i.e., the dialect spoken in Paris, Webb (2009) states that approximant realizations are preferred in coda, intervocalic and word-initial positions after resyllabification; fricatives are more common word-initially and in complex onsets; and voiceless realizations are favored before and after voiceless consonants, with voiced productions preferred elsewhere. However, Webb acknowledges that the precise realizations are subject to much variation and the previous observations are not always followed. Taking Webb’s description as a starting point, this study explores the idea that French rhotic production is subject to much variation but that such variation is conditioned by several factors, including internal and external variables. -

French Studies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository 1 Prepared for: The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, Volume 71 (survey year 2009; to appear in 2011). [TT]French Studies [TT]Language and Linguistics [A]By Paul Rowlett, University of Salford [H2]1. General The proceedings of the first Congrès mondial de linguistique française, held in Paris in July 2008, have been published online at http://www.linguistiquefrancaise.org/index.php?option+ toc&url=/articles/cmlf/abs/2008/01/contents/contents.html/. The 187 contributions are divided into thematic sections many of which will be of interest to readers. FM, special issue, *‘Tendances actuelles de la linguistique française’, 2008, 140 pp., includes contributions by C. Marchello-Nizia, F. Gadet, C. Blanche-Benveniste, and others. *Morin Vol. contains a broad selection of fifteen contributions by J. Durand, F. Gadet, R. S. Kayne, B. Laks, A. Lodge, and others, covering the phonology and morphosyntax of standard and regional varieties (including North American), from diachronic, synchronic, and sociolinguistic perspectives. [H2]2. History of the Language *Sociolinguistique historique du domaine gallo-roman: enjeux et méthodologies, ed. D. Aquino- Weber et al., Oxford, Lang, xiv + 335 pp., includes an introduction and 14 other contributions. S. Auroux, ‘Instrumentos lingüísticos y políticas lingüísticas: la construcción del francés’, Revista argentina de historiografía lingüística, 1:137–49, focuses on the policies and tools which underlay the ‘construction’ of Fr. and concludes that the historical milestones are more political and literary than linguistic, revolving around efforts to impose the monarch’s variety as standard and the ‘grammatization’ of Fr. -

French Guianese Creole Its Emergence from Contact

journal of language contact 8 (2015) 36-69 brill.com/jlc French Guianese Creole Its Emergence from Contact William Jennings University of Waikato [email protected] Stefan Pfänder FRIAS and University of Freiburg [email protected] Abstract This article hypothesizes that French Guianese Creole (fgc) had a markedly different formative period compared to other French lexifier creoles, a linguistically diverse slave population with a strong Bantu component and, in the French Caribbean, much lower or no Arawak and Portuguese linguistic influence.The historical and linguistic description of the early years of fgc shows, though, that the founder population of fgc was dominated numerically and socially by speakers of Gbe languages, and had almost no speakers of Bantu languages. Furthermore, speakers of Arawak pidgin and Portuguese were both present when the colony began in Cayenne. Keywords French Guianese Creole – Martinique Creole – Arawak – tense and aspect – founder principle 1 Introduction French Guianese Creole (hereafter fgc) emerged in the South American col- ony of Cayenne in the late 1600s. The society that created the language was superficially similar to other Caribbean societies where lexically-French cre- oles arose. It consisted of slaves of African origin working on sugar plantations for a minority francophone colonial population. However, from the beginning © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2015 | doi 10.1163/19552629-00801003Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 09:17:10PM via free access <UN> French Guianese Creole 37 fgc was quite distinct from Lesser Antillean Creole. It was “less ridiculous than that of the Islands” according to a scientist who lived in Cayenne in the 1720s (Barrère 1743: 40). -

A National Bilingual Education Policy for the Economic and Academic Empowerment of Youth in St. Lucia, West Indies Gabriella Bellegarde SIT Graduate Institute

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Summer 8-18-2016 A National Bilingual Education Policy for the Economic and Academic Empowerment of Youth in St. Lucia, West Indies Gabriella Bellegarde SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Education Economics Commons, First and Second Language Acquisition Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Linguistic Anthropology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bellegarde, Gabriella, "A National Bilingual Education Policy for the Economic and Academic Empowerment of Youth in St. Lucia, West Indies" (2016). Capstone Collection. 2928. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/2928 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A National Bilingual Education Policy for Youth Economic and Academic Empowerment in St. Lucia, West Indies Gabriella M. Bellegarde SIT Graduate Institute, Washington D.C. BILINGUAL EDUCATION FOR YOUTH IN ST. LUCIA 2 Consent to Use of Capstone I hereby grant permission for World Learning to publish my capstone on its websites and in any of its digital/electronic collections, and to reproduce and transmit my capstone electronically. -

Creole-Speaking Countries and Their Populations* (Les Pays Créolophones Et Leurs Populations)

Creole-Speaking Countries and their Populations* (Les pays créolophones et leurs populations) (French-lexifier creoles) SURFACE CENTRE OF COUNTRY AREA POPULATION LANGUAGES SPOKEN ADMINISTRATION (km2) Dominica 751 100,000 Roseau English, Antillean Creole English, Antillean Creole Grenada 344 100,000 Saint-George (residual) Guadeloupe 1,709 422,496 Basse-Terre French, Antillean Creole French, French Guiana Creole, various Amerindian languages, French 91,000 157,277 Cayenne Hmong, Chinese, Haitian Guiana Creole, various Businenge languages (English-based creoles) Haiti 27,750 7,000,000 Port-au-Prince Haitian Creole, French English, Louisiana Louisiana 235,675 4,000,000 Baton Rouge Creole (residual), Cajun Martinique 1,100 381,441 Fort-deFrance French, Antillean Creole English, French, Mauritian Creole, Mauritius 2,040 1,100,000 Part-Louis Bhojpuri, Hindi, Urdu, and some other Indian languages, Chinese Réunion 2,511 707,758 Saint-Denis French, Réunion Creole St. Lucia 616 150,000 Castries English, Antillean Creole English, Antillean Creole St. Thomas 83 56,000 Charlotte Amalie (residual) English, French, Seychelles 410 70,000 Victoria Seychelles Creole English, Antillean Creole Trinidad 5,128 1,300,000 Port-of-Spain (residual) Table 7.1 An overview of creole-speaking countries N.B. The figures indicated here for the four French overseas ‘départements’, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique, and Réunion, have been taken from the 1999 census. NOTE: Do not be misled by this table which merely aims to give a few geographical details. The reason for showing the languages spoken in the final column is to complete the information with respect to the possible multilingualism of the ‘département’ or State in question but it is in no way possible to deduce from this the number of speakers of one or other of the languages spoken. -

Lexicography in the French Caribbean: an Assessment of Future Opportunities

LEXICOGRAPHY IN GLOBAL CONTEXTS 619 Lexicography in the French Caribbean: An Assessment of Future Opportunities Jason F. Siegel The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus E-mail: [email protected] Abstract While lexicography in the Hispanophone Caribbean has flourished, and to a lesser extent in the territories of the Caribbean whose official language is English, dictionaries of the French-official Caribbean (except Haiti) have been quite limited. But for the rest of the French-official Caribbean, there remains much work to do. In this paper, I assess the state of lexicography in the French-official Caribbean, as well as the possibilities for fu- ture work. There are six principal areas of lexicographic documentation to be developed. The first, most urgent task is the documentation of the endangered St Barth French. The next priority is multilingual lexicography for the Caribbean region. The third priority is multilingual lexicography of French Guiana, home to endangered Amerindian, Creole and immigrant languages. Fourth, there is a largely pristine area of lexicographic work for the English varieties of the French Caribbean. The fifth area of work to be developed is monolingual lexicog- raphy of French-based Creoles. Lastly, there is exploratory work to be done on the signed language varieties of the French-official Caribbean. The paper concludes with a discussion of the role that the Richard and Jeannette Allsopp Centre for Caribbean Lexicography can play in the development of these areas. Keywords: minority languages, bilingual lexicography, French Caribbean 1 Introduction Overseas French (le français d’outre-mer) is a fairly important topic in French linguistics. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages

DigitalResources SIL eBook 25 ® The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook SIL International ® 2012 SIL e-Books 25 2012 SIL International ® ISBN: 978-1-55671-268-5 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair-Use Policy: Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor George Huttar Volume Editor Dirk Kievit Managing Editor Bonnie Brown Compositor Margaret González Abstract This study examines the four English-lexifier creole languages spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago. These languages are classified using a comparison of some of the markers of key grammatical features identified as being typical of pidgin and creole languages. The classification is based on a scoring system that takes into account the potential problems in translation due to differences in the mapping of semantic notions. -

Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language Of

New speaker language and identity: Practices and perceptions around Breton as a regional language of France Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Merryn Davies-Deacon B.A., M.A. February, 2020 School of Arts, English, and Languages Abstract This thesis focuses on the lexicon of Breton, a minoritised Celtic language traditionally spoken in western Brittany, in north-west France. For the past thirty years, much work on Breton has highlighted various apparent differences between two groups of speak- ers, roughly equivalent to the categories of new speakers and traditional speakers that have emerged more universally in more recent work. In the case of Breton, the concep- tualisation of these two categories entails a number of linguistic and non-linguistic ste- reotypes; one of the most salient concerns the lexicon, specifically issues around newer and more technical vocabulary. Traditional speakers are said to use French borrowings in such cases, influenced by the dominance of French in the wider environment, while new speakers are portrayed as eschewing these in favour of a “purer” form of Breton, which instead more closely reflects the language’s membership of the Celtic family, in- volving in particular the use of neologisms based on existing Breton roots. This thesis interrogates this stereotypical divide by focusing on the language of new speakers in particular, examining language used in the media, a context where new speakers are likely to be highly represented. The bulk of the analysis presented in this work refers to a corpus of Breton gathered from media sources, comprising radio broadcasts, social media and print publications. -

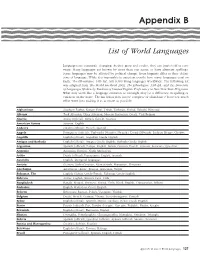

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani