Practices and Perceptions Around Breton As a Regional Language Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New School Year for the Breton Language

Viviane Helias – one of four new members of the Order of the Ermine – see page 10 No. 108 Nov. 2008 1 BRO NEVEZ 108 November 2008 ISSN 0895 3074 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Lois Kuter, Editor (215) 886-6361 169 Greenwood Ave., B-4 [email protected] Jenkintown, PA 19046 U.S.A. U.S. ICDBL website: www.icdbl.com Also available via: www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm ___________________________________________________________________________________________ The U.S. Branch of the International Committee for the Defense of the Breton Language (U.S. ICDBL) was incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation on October 20, 1981. Bro Nevez ("new country" in the Breton language) is the newsletter produced by the U.S. ICDBL It is published quarterly: February, May, August and November. Contributions, letters to the Editor, and ideas are welcome from all readers and will be printed at the discretion of the Editor. The U.S. ICDBL provides Bro Nevez on a complimentary basis to a number of language and cultural organizations in Brittany to show our support for their work. Your Membership/Subscription allows us to do this. Membership (which includes subscription) for one year is $20. Checks should be in U.S. dollars, made payable to “U.S. ICDBL” and mailed to Lois Kuter at the address above. Ideas expressed within this newsletter are those of the individual authors, and do not necessarily represent ICDBL philosophy or policy. For information about the Canadian ICDBL contact: Jeffrey D. O’Neill, PO Box 14611, 50 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M8L-5R3, CANADA (e-mail: [email protected]). Telephone: (416) 264-0475. -

05/07/17 14:01

GUIDE DES LOISIRS.indd 2-3 05/07/17 14:01 É DITORIAL Voici l’édition 2017/2018 du guide des associations à Vannes. L’une des forces de la ville de Vannes est son tissu associatif et ce guide en fait l’écho en vous présentant près de 700 associations locales. Je remercie chaleureusement tous les bénévoles engagés dans les associations qui, en donnant de leur temps, de leur enthousiasme, en faisant profiter le public de leurs compétences, font de Vannes une ville dynamique où chacun est assuré de trouver une ou des activités de loisirs à pratiquer tout au long de l’année. J’espère que ce guide vous permettra de trouver l’association qui répondra à vos attentes. David ROBO, Maire de Vannes Setu amañ sturlevr diverrañsoù Gwened 2017/2018. He rouedad kevredigezhioù a ro un tamm mat a vegon da gêr Gwened. Tost 700 kevredigezh zo kinniget deoc’h er sturlevr-mañ. A-greiz kalon e trugarekaan razh an dud a-youl-vat engouestlet er c’hevredigezhioù. Dre roiñ un tamm ag o amzer hag o birvilh, dre ranniñ o barregezhioù gant an dud, e roont lañs da gêr Gwened ma c’hell an holl kavouet un dra bennak pe meur a dra d’ober a-hed ar blez. Esper am eus e kavot er sturlevr-mañ ar gevredigezh a responto d’ho ezhommoù. David Robo Maer Gwened S OMM A IRE A B ACCOMPAGNEMENT SCOLAIRE - SOUTIEN SCOLAIRE 6 BADMINTON 18 ACCUEIL DE LOISIRS SANS HÉBERGEMENT (A.L.S.H) 6 - 7 BASKET-BALL 19 ANIMATION SCIENTIFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE 7 BÉBÉS DANS L’EAU 19 AQUABIKE 7 BÉNÉVOLAT ASSOCIATIF 19 AQUAGYM 8 BIBLIOTHÈQUES / MÉDIATHÈQUES 19 - 21 AQUANATAL 8 BILLARD 21 AQUATRAMPOLINE 8 BMX -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance Committee: _________________________________ Jean-Pierre Montreuil, Supervisor _________________________________ Cinzia Russi _________________________________ Carl Blyth _________________________________ Hans Boas _________________________________ Anthony Woodbury Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my family for their patience and support, their belief in me, and their love. I would like to thank my supervisor Jean-Pierre Montreuil for his advice, his inspiration, and constant support. Thank you to my committee members Cinzia Russi, Carl Blyth, Hans Boas and Anthony Woodbury for their guidance in this project and their understanding. Special thanks to Christian Lefeuvre who let me stay with him during the summer 2009 in Langan and helped me realize this project. For their help and support, I would like to thank Rosalie Grot, Pierre Gardan, Christine Trochu, Shaun Nolan, Bruno Chemin, Chantal Hermann, the associations Bertaèyn Galeizz, Chubri, l’Association des Enseignants de Gallo, A-Demórr, and Gallo Tonic Liffré. For financial support, I would like to thank the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin for the David Bruton, Jr. -

Language Transmission in France in the Course of the 20Th Century

https://archined.ined.fr Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century François Héran, Alexandra Filhon et Christine Deprez Version Libre accès Licence / License CC Attribution - Pas d'Œuvre dérivée 4.0 International (CC BY- ND) POUR CITER CETTE VERSION / TO CITE THIS VERSION François Héran, Alexandra Filhon et Christine Deprez, 2002, "Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century", Population & Societies: 1-4. Disponible sur / Availabe at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12204/AXCwcStFDxhNsJusqTx6 POPU TTIION &SOCIÉTTÉÉS No.FEBRU ARY37 20062 Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century François Héran *, Alexandra Filhon ** and Christine Deprez *** “French shall be the only language of education”, pro- Institute of Linguistics’ languages of the world data- claimed the Ministerial Order of 7 June 1880 laying base [4]. The ten most frequently recalled childhood down the model primary school regulations. “The lan- languages are cited by two thirds of the respondents, guage of the Republic is French”, recently added arti- while a much larger number are recalled by a bare cle 2 of the Constitution (1992). But do families follow handful. the strictures of state education and institutions? What The Families Survey distinguishes languages were the real linguistic practices of the population of “usually” spoken by parents with their children (fig- France in the last century? Sandwiched between the ure 1A) from those which they “also” spoke to them, monopoly of the national language and -

REFLECTIONS on LIFE: CREOLES, the INTERSECTION of MANY PEOPLES Growing up As Little People, My Siblings and I, As Well As Our Re

REFLECTIONS ON LIFE: CREOLES, THE INTERSECTION OF MANY PEOPLES Growing up as little people, my siblings and I, as well as our relatives, friends and neighbors, sponged up everything around us, unaware that a Creole culture was the atmosphere and environment that we lived, breathed and ingested constantly. It was our father who spoke Cajun, the old French from Canada, and our mother who spoke Creole, the oft-fractured French so dear to all who are part of that culture. A many-splendored culture, it has purloined gems of all kinds from other cultures, in the process of creating its own distinctive jewels unlike any in the world. From rich goodness and talent in every walk of life, we are a flavorful gumbo appetizing to all. With an incredible length and breadth, Creoles span all the color spectrum from deep ebony to dark chocolate to milk chocolate to teasing tan to the ambiguous ivory-complected to sepia to the reddish briqué to high yellow to white. Technically, black is not a color, for it is the absence of visible light. Neither is white a color, for it contains all the wavelengths of visible light. So what is this black/white fuss all about? In any case, most of us are of Afro- Euro-Asian (First American) extraction – quite a bit in addition to what we usually call African American. Seizing upon these broad-based commonalities, confessed Creole Georgina Dhillon from the Seychelles, who later moved to London, had a dream to unite the formidable concentrations of Creoles: Antillean Creole, spoken among 100,000 in Dominica, “The nature isle of the Caribbean”; Antillean Creole, among 100,000 in Grenada; Antillean Creole, among 422,496 in Guadeloupe; French Guiana Creole and Haitian Creole, among 157,277 in French Guiana; Haitian Creole, among 7,000,000 in Haiti; Antillean Creole, among 381,441 in Martinique; Mauritian Creole, among 1,100,000 in Mauritius; Réunion Creole, among 707,758 in Réunion; Antillean Creole, among 150,000 in St. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future. A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/12v9d1gx Author Marcus, Nicole Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gary Holland, Chair Professor Leanne Hinton Professor Johanna Nichols Fall 2010 The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance © 2010 by Nicole Elise Marcus Abstract The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gary Holland, Chair The énonciatif system is a defining linguistic feature of Gascon, an endangered Romance language spoken primarily in southwestern France, separating it not only from its neighboring Occitan languages, but from the entire Romance language family. This study examines this preverbal particle system from a diachronic and synchronic perspective to shed light on issues of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance. The diachronic source of this system has important implications regarding its current and future status. My research indicates that this system is an ancient feature of the language, deriving from contact between the original inhabitants of Gascony, who spoke Basque or an ancestral form of the language, and the Romans who conquered the region in 56 B.C. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Celts and Celtic Languages

U.S. Branch of the International Comittee for the Defense of the Breton Language CELTS AND CELTIC LANGUAGES www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm A Clarification of Names SCOTLAND IRELAND "'Great Britain' is a geographic term describing the main island GAIDHLIG (Scottish Gaelic) GAEILGE (Irish Gaelic) of the British Isles which comprises England, Scotland and Wales (so called to distinguish it from "Little Britain" or Brittany). The 1991 census indicated that there were about 79,000 Republic of Ireland (26 counties) By the Act of Union, 1801, Great Britain and Ireland formed a speakers of Gaelic in Scotland. Gaelic speakers are found in legislative union as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and all parts of the country but the main concentrations are in the The 1991 census showed that 1,095,830 people, or 32.5% of the population can Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom does not include the Western Isles, Skye and Lochalsh, Lochabar, Sutherland, speak Irish with varying degrees of ability. These figures are of a self-report nature. Channel Islands, or the Isle of Man, which are direct Argyll and Bute, Ross and Cromarly, and Inverness. There There are no reliable figures for the number of people who speak Irish as their dependencies of the Crown with their own legislative and are also speakers in the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow and everyday home language, but it is estimated that 4 to 5% use the language taxation systems." (from the Statesman's handbook, 1984-85) Aberdeen. regularly. The Irish-speaking heartland areas (the Gaeltacht) are widely dispersed along the western seaboards and are not densely populated. -

The Cornish Language in Education in the UK

The Cornish language in education in the UK European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by CORNISH The Cornish language in education in the UK | 2nd Edition | c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Albanian; the Albanian language in education in Italy Aragonese; the Aragonese language in education in Spain and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Asturian; the Asturian language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) of Fryslân. Basque; the Basque language in education in France (2nd ed.) Basque; the Basque language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) Breton; the Breton language in education in France (2nd ed.) Catalan; the Catalan language in education in France Catalan; the Catalan language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Cornish; the Cornish language in education in the UK (2nd ed.) and Language Learning, 2019 Corsican; the Corsican language in education in France (2nd ed.) Croatian; the Croatian language in education in Austria Danish; The Danish language in education in Germany ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Frisian; the Frisian language in education in the Netherlands (4th ed.) 2nd edition Friulian; the Friulian language in education in Italy Gàidhlig; The Gaelic Language in Education in Scotland (2nd ed.) Galician; the Galician language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, German; the German language in education in Alsace, France (2nd ed.) provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European German; the German language in education in Belgium Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

Brittany's Celtic Past

A JOURNAL OF ORTHODOX FAITH AND CULTURE ROAD TO EMMAUS Help support Road to Emmaus Journal. The Road to Emmaus staff hopes that you find our journal inspiring and useful. While we offer our past articles on-line free of charge, we would warmly appreciate your help in covering the costs of producing this non-profit journal, so that we may continue to bring you quality articles on Orthodox Christianity, past and present, around the world. Thank you for your support. Please consider a donation to Road to Emmaus by visiting the Donate page on our website. BRITTANY’S CELTIC PAST Russian pilgrims following the Tro Breizh route speak with Fr. Maxime Le Diraison, Breton historian and pastor of the Church of St. Anna in Lannion, Brittany. RTE: Father Maxime, can you orient us to Brittany? FR. MAXIME: Yes. Today we commonly use the term Great Britain, but not many people realize that its counterpart across the Channel, Little Britain or Brittany, was more culturally tied to Cornwall, Wales, and Ireland than to Gaul (France). Christianity came here very early. In Little Brittany, also called Amorica, the very first missionaries were two 3rd-century martyrs, Rogasian and Donasian. Igor: Didn’t Christianity take root earlier in France? FR. MAXIME: Yes, it did. When the Church was first established in France, there was no France as we know it now; it was called Gallia (Gaul). Brittany, where I am from, and which is now a part of northern France, was then another region, a Celtic culture. But in the Roman, Latin region of Gaul there were great early saints – not apostles, but certainly disciples of the apostles, the second and third generation. -

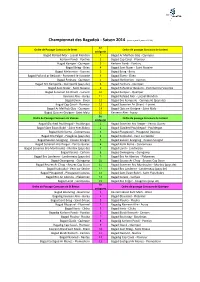

2014 (Mise À Jour 8 Janvier 2014)

Championnat des Bagadoù ‐ Saison 2014 (mise à jour 8 janvier 2014) 1e Ordre de Passage Concours de Brest Ordre de passage Concours de Lorient catégorie Bagad Roñsed Mor ‐ Locoal Mendon 1 Bagad Ar Meilhoù Glaz ‐ Quimper Kerlenn Pondi ‐ Pontivy 2 Bagad Cap Caval ‐ Plomeur Bagad Kemper ‐ Quimper 3 Kerlenn Pondi ‐ Pontivy Bagad Brieg ‐ Briec 4 Bagad Sant Nazer ‐ Saint Nazaire Bagad Melinerion ‐ Vannes 5 Bagad Brieg ‐ Briec Bagad Pañvrid ar Beskont ‐ Pommerit le Vicomte 6 Bagad Elven ‐ Elven Bagad Penhars ‐ Quimper 7 Bagad Melinerion ‐ Vannes Bagad Bro Kemperle ‐ Quimperlé (pays de) 8 Bagad Penhars ‐ Quimper Bagad Sant Nazer ‐ Saint Nazaire 9 Bagad Pañvrid ar Beskont ‐ Pommerit le Vicomte Bagad Sonerien An Oriant ‐ Lorient 10 Bagad Kemper ‐ Quimper Kevrenn Alre ‐ Auray 11 Bagad Roñsed Mor ‐ Locoal Mendon Bagad Elven ‐ Elven 12 Bagad Bro Kemperle ‐ Quimperlé (pays de) Bagad Cap Caval ‐ Plomeur 13 Bagad Sonerien An Oriant ‐ Lorient Bagad Ar Meilhoù Glaz ‐ Quimper 14 Bagad Quic en Groigne ‐ Saint Malo Bagad Quic en Groigne ‐ Saint Malo 15 Kevrenn Alre ‐ Auray 2e Ordre de Passage Concours de Vannes Ordre de passage Concours de Lorient catégorie Bagad Glaziked Pouldregad ‐ Pouldergat 1 Bagad Sonerien Bro Dreger ‐ Perros Guirec Bagad Sant Ewan Bubri ‐ Saint Yves Bubry 2 Bagad Glaziked Pouldregad ‐ Pouldergat Bagad Konk Kerne ‐ Concarneau 3 Bagad Plougastell ‐ Plougastel Daoulas Bagad Bro Felger ‐ Fougères (pays de) 4 Bagad Kadoudal ‐ Vern sur Seiche Bagad Saozon‐Sevigneg ‐ Cesson Sevigné 5 Bagad Saozon‐Sevigneg ‐ Cesson Sevigné Bagad Sonerien Bro