Bonsai Northwest Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

The Karin Ikebana Exhibition

Sairyuka - Art and ancient Asian philosophy rooted in nature KARIN-en vol.6 Sairyuka No. 35 Supplementary Karin-en News No. 6, January 2018 Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels ... The Karin Ikebana Exhibition Kanazawa / Tokyo “ Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels - The Karin Ikebana Exhibitions” were held in Kanazawa and Tokyo, co- inciding with the Hina festival and Boy’s Day celebration (Sairyuka No. 35). This page and the next show designs from the Tokyo exhibition. Sairyuka - Ikebana of the Wind Camellia (single-variant); by Karin Painting (hanging scroll) - “Sea bream”; by Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Boat-form ceramic vase and square/circular stand (thick board) Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda (ceramics), Kazuhiko Tada (stand) Koryu Association, Komagome, Tokyo 23 November Held together with the Koryu Ikebana Exhi- bition (continued on p2) Jiyuka (versatile arrangement); by Risei Morikawa Pine, camellia, eucalyptus, lily, soaproot, kori willow, other Vessel: Reika - beech, other; by Box-form ceramic vase Design by Karin Hosei Sakamoto Painting Production by Yatomi Maeda (hanging scroll) - “frog”; by Positioned at the venue entrance Karin Mounting by Akira Na- gashima Vessel: Ceramic “ kagamigata ” (parabolic) vase Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda 1 The Karin Ikebana Exhibition 23 November23 Continued from page page 1 from Continued KoryuAssociation, Komagome, Sairyuka - Five Ikebana: Camellia (single tone) (From left: Wind Ikebana, Water Ikebana, Sword Ikebana, Earth Ikebana, Fire Ikebana): by Karin, Kyuuka Yamaki, Kyuuka Higashimori Paintings (hanging scroll) - From left: Enso-Wind, Enso-Water, Enso-Sword, Enso-Earth, Enso-Fire: Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Square-circular ceramic vase Design by Karin Tokyo Production by Yatomi Maeda The Tokyo “Karin Ikebana Exhibition” was held on 23 【Right】 November at the Koryu Reika - (Japanese yew), other: by Association in Komagome, Ribin Okamoto alongside the established Painting (hanging scroll) - “sword”; Koryu Shoseikai Ikebana by Karin exhibition. -

Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan

Educating Minds and Hearts to Change the World A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Volume IX ∙ Number 2 June ∙ 2010 Pacific Rim Copyright 2010 The Sea Otter Islands: Geopolitics and Environment in the East Asian Fur Trade >>..............................................................Richard Ravalli 27 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Shadows of Modernity: Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan Editorial >>...............................................................Nicholas Mucks 36 Consultants Barbara K. Bundy East Timor and the Power of International Commitments in the American Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Decision Making Process >>.......................................................Christopher R. Cook 43 Editorial Board Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Syed Hussein Alatas: His Life and Critiques of the Malaysian New Economic Mark Mir Policy Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy >>................................................................Choon-Yin Sam 55 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Betel Nut Culture in Contemporary Taiwan >>..........................................................................Annie Liu 63 A Note from the Publisher >>..............................................Center for the Pacific Rim 69 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It Center for the Pacific Rim welcomes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific 2130 Fulton St, LM280 region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- San Francisco, CA mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. -

Bonsai Pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1

Bonsai pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1 THE BONSAI COLLECTION The Chicago Botanic Garden’s bonsai collection is regarded by bonsai experts as one of the best public collections in the world. It includes 185 bonsai in twenty styles and more than 40 kinds of plants, including evergreen, deciduous, tropical, flowering and fruiting trees. Since the entire collection cannot be displayed at once, select species are rotated through a display area in the Education Center’s East Courtyard from May through October. Each one takes the stage when it is most beautiful. To see photographs of bonsai from the collection, visit www.chicagobotanic.org/bonsai. Assembling the Collection Predominantly composed of donated specimens, the collection includes gifts from BONSAI local enthusiasts and Midwest Bonsai Society members. In 2000, Susumu Nakamura, a COLLECTION Japanese bonsai master and longstanding friend of the Chicago Botanic Garden, donated 19 of his finest bonsai to the collection. This A remarkable collection gift enabled the collection to advance to of majestic trees world-class status. in miniature Caring for the Collection When not on display, the bonsai in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s collection are housed in a secured greenhouse that has both outdoor and indoor facilities. There the bonsai are watered, fertilized, wired, trimmed and repotted by staff and volunteers. Several times a year, bonsai master Susumu Nakamura travels from his home in Japan to provide guidance for the care and training of this important collection. What Is a Bonsai? Japanese and Chinese languages use the same characters to represent bonsai (pronounced “bone-sigh”). -

Advanced Master Gardener Landscape Gardening For

ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER LANDSCAPE GARDENING FOR GARDENERS 2002 The Quest Continues 11 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 LARRY A. SAGERS PROFFESOR UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY 21 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 GRETCHEN CAMPBELL • MASTER GARDENER COORDINATOR AT THANKSGIVING POINT INSTITUE 31 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 41 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Life according to the Bible began in a garden. • Wherever that garden was located that was planted eastward in Eden, there were many plants that Adam and Eve were to tend. • The Garden provided”every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” 51 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Other cultures have similar stories. • Stories come from Native Americans African tribes, Polynesians and Aborigines and many other groups of gardens as a place of life 61 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Teachings and legends influence art, religion, education and gardens. • The how and why of the different geographical and cultural influences on Landscape Gardening is the theme of the 2002 Advanced Master Gardening course at Thanksgiving Point Institute. 71 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Earliest known indications of Agriculture only go back about 10,000 years • Bouquets of flowers have been found in tombs some 60,000 years old • These may have had aesthetic or ritual roles 81 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Evidence of gardens in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates -

Samurai Life in Medieval Japan

http://www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history Handout M2 (Print Version) Page 1 of 8 Samurai Life in Medieval Japan The Heian period (794-1185) was followed by 700 years of warrior governments—the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Tokugawa. The civil government at the imperial court continued, but the real rulers of the country were the military daimy class. You will be using art as a primary source to learn about samurai and daimy life in medieval Japan (1185-1603). Kamakura Period (1185-1333) The Kamakura period was the beginning of warrior class rule. The imperial court still handled civil affairs, but with the defeat of the Taira family, the Minamoto under Yoritomo established its capital in the small eastern city of Kamakura. Yoritomo received the title shogun or “barbarian-quelling generalissimo.” Different clans competed with one another as in the Hgen Disturbance of 1156 and the Heiji Disturbance of 1159. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki is a hand scroll showing the armor and battle strategies of the early medieval period. The conflict at the Sanj Palace was between Fujiwara Nobuyori and Minamoto Yoshitomo. As you look at the scroll, notice what people are wearing, the different roles of samurai and foot soldiers, and the different weapons. What can you learn about what is involved in this disturbance? What can you learn about the samurai and the early medieval period from viewing this scroll? What information is helpful in developing an accurate view of samurai? What preparations would be necessary to fight these kinds of battles? (Think about the organization of people, equipment, and weapons; the use of bows, arrows, and horses; use of protective armor for some but not all; and the different ways of fighting.) During the Genpei Civil War of 1180-1185, Yoritomo fought against and defeated the Taira, beginning the Kamakura Period. -

Ws \\ I: I, I; I\ Si

x i: w s \\ i: i, i; i\ s i: FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAJOR EXHIBITION OF JAPANESE ART AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Exhibition To Appear Only In Washington WASHINGTON, August 25, 1988- The art of the daimyo, feudal lords who ruled the provinces of Japan for nearly 700 years, will be the focus of a new exhibition, Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185 - 1868, opening this fall at the National Gallery of Art. The exhibition will bring together more than 450 Japanese-owned works of art that express the values that helped shape the aesthetic ideals and social character of the Japanese nation in its feudal age. An unprecedented number of objects officially designated by the Japanese government as National Treasures, Important Cultural Properties and Important Art Objects will be on view in what will be the largest exhibition of its kind ever presented in the West, or even in Japan. This exhibition will appear only in Washington. Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185 - 1868 will be in the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, Oct. 30, 1988 through Jan. 23, 1989. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, The Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, and The Japan Foundation. The R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, The Yomiuri Shimbun and The Nomura Securities Co., Ltd. made the exhibition possible. Japan Air Lines provided transport. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

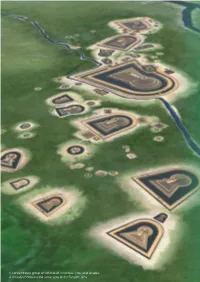

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures.