Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Vogtei Des Klosters Admont Und Die Babenberger

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Jahrbuch für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich Jahr/Year: 1976 Band/Volume: 42 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hausmann Friedrich Artikel/Article: Die Vogtei des Klosters Admont und die Babenberger 95-128 ©Verein für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich;download http://www.noe.gv.at/noe/LandeskundlicheForschung/Verein_Landeskunde.html DIE VOGTEI DES KLOSTERS ADMONT UND DIE BABENBERGER Von Friedrich Hausmann Die engen Beziehungen der Babenberger zur Steiermark beginnen keineswegs erst mit den Georgenberger Abmachungen des Jahres 1186, die nach dem Ableben des letzten Traungauers und ersten steirischen Herzogs Ottokar IV. im Mai 1192 den Übergang seines Herrschaftsbereiches an jene herbeiführten. Sie gehen viel mehr zurück auf die Ehe der Elisabeth, der Tochter des österreichischen Mark grafen Leopold II., mit dem karantanischen Markgrafen Ottokar II., dem Urgroßvater des vorgenannten gleichnamigen Herzogs, mit der die für den Erbfall maßgebende nahe Verwandtschaft der beiden Fürstenhäuser geschaffen wurde. Von besonderer Bedeutung war aber auch der Erwerb der Hauptvogtei über das Kloster Admont und seinen weitgestreuten großen Besitz in den 60er Jahren des 12. Jahrhunderts durch Herzog Heinrich II. von Österreich. Mit ihr erlangten die Babenberger sehr gewichtige Rechte und Einfluß in der Steiermark und anderswo, die, insbesondere nach der Vereinigung der beiden Länder, von großem Wert für den Ausbau ihrer landesfürstlichen Herrschaft waren. Das genaue Datum und die im einzelnen maßgeblichen Umstände sowie die rechtlichen Bedingungen des Übergangs der Vogtei sind uns leider in keiner Quelle überliefert. Dafür hören wir, daß es bald Meinungsverschiedenheiten zwischen dem österreichischen Herzog und dem Erzbischof von Salzburg gab, da dieser die Vogtei als ein vom Erzstift abhängiges Lehen, jener dagegen als eine Erbvogtei betrachtete. -

Bürgerinformation

Zugestellt durch Österreichische Post Nr. 20 | September 2015 Bürgerinformation Goldregen bei Flora 15 Veranstaltungssommer mit vielen Highlights Hauser Vereine aktiv und erfolgreich Kinderspielplatz 2 | 15 offiziell eröffnet Foto: Michaela Schnepfleitner 2 FRAKTIONEN SEPTEMBER 2015 Projekte sind bei uns sensatio- bezeichnen kann. Ich glaube ge- nell! So sage ich herzlichen Dank rade deshalb könnte man sich die für die tolle Arbeit in den Dorfge- Inserate in einer Bezirkszeitung meinschaften, unseren Blumen- sparen, die als Bürgerservice Haus ampelbetreuerInnen, unseren bei- benannt werden und in denen von den Gärtnerinnen, an alle die ihre einer politischen Partei nur die Häuser schön gestalten und alle halbe Wahrheit über den Ablauf die Hand anlegen, um unsere Ge- unserer Gemeinderatssitzungen meinde aufblühen zu lassen. Hier berichtet wird. Ich würde es als gebührt für die Projekt– und Koor- schade empfinden, wenn durch sol- dinationsarbeit unserer Projektlei- che Aktionen die Zusammenarbeit terin Michaela Schnepfleitner und für die Zukunft wieder darunter Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen und unseren beiden Gemeinderäten leiden müsste. Transparenz, offene Gemeindebürger unserer schönen Manuela Danklmayer und Fredi und ehrliche Information der Bür- Marktgemeinde Haus! Pressl ein besonderer Dank! Herz- ger, ist auch meiner Meinung nach lichst gratuliere ich unseren vielen eine sehr wichtige Angelegenheit, In diesem Sommer konnten wir Preisträgern in den verschiedenen deshalb freue ich mich, alle Hau- uns alle wieder über eine wun- Kategorien, allen voran der Fami- serinnen und Hauser im Oktober derschön blühende Gemeinde lie Angelika und Willi Walcher vlg. zu einer Bürgerversammlung ein- freuen. Auch unsere Urlaubsgäste Mühlbacher zur Goldmedaille! zuladen. bestaunten die Blumenpracht. An- gefangen bei den öffentlichen Plät- Auf den folgenden Seiten dieser Wir erleben momentan eine span- zen über blühende Häuser, von 20. -

Bürgerinformation

Zugestellt durch Österreichische Post Amtliche Mitteilung Nr. 40 | Dezember 2020 Bürgerinformation Frohe Weihnachten und ein glückliches neues Jahr 2021 wünschen herzlichst Bürgermeister Stefan Knapp Orange the world und der gesamte Gemeinderat Stoppt Gewalt an Frauen der Marktgemeinde Haus Lichterpfad 2020 Das innere Leuchten FF Haus Fehlerfreie Leistungsprüfung Alte Bilder gesucht Archiv der Erinnerungen 3 | 20 2 FRAKTIONEN DEZEMBER 2020 litik entschieden. Das schafft somit für Kraml und seiner Frau Edda zu einem die Hauserinnen und Hauser, besonders ganz besonderen Jubiläum gratulieren – für die Jugend, neue Chancen in un- sie feierten die Diamantene Hochzeit. serer Gemeinde. Danke an alle für das Herzlichen Glückwunsch noch einmal Vertrauen. Somit sind die acht Ge- zu eurem 60-Jahr-Ehejubiläum. meinderäte der Liste Haus sowie ich Als stolzer Vater, aber auch als Bür- als Bürgermeister gefordert, die Wahl- germeister, möchte ich meinem Sohn versprechen umzusetzen: „Die Gemein- Sebastian ganz herzlich zur Eröffnung Bürgermeister schaft und den Zusammenhalt inner- des neuen Stefflbäck-Betriebes in Stefan Knapp halb der Gemeinde fördern, Platz für die Oberhaus gratulieren. Es erfüllt mich Jugend in unserer Gemeinde schaffen, mit großer Freude und ich wünsche Liebe Hauerinnen und Hauser, die Zweitwohnsitzproblematik in den ihm viel Erfolg für sein Unternehmen. liebe Jugend! Griff bekommen sowie den Ausverkauf Liebe Hauerinnen und Hauser, lie- Das Jahr 2020 ist ein besonderes Jahr der Heimat stoppen.“. Einiges ist uns be Jugend, ich bin sehr dankbar und und wird in die Geschichte eingehen. schon gelungen: Wir haben eine Bau- stolz, dass ich in unserer Gemeinde als Viele Lebensveränderungen hat es auf sperre ausgerufen, somit können wir euer Bürgermeister arbeiten darf. -

Bürgerinformation

Zugestellt durch Österreichische Post Amtliche Mitteilung Nr. 39 | September 2020 Bürgerinformation Neue Gemeindeführung wurde angelobt Hauser Kaibling beste Sommer-Bergbahn Memory Sportcamp fand großen Anklang Platin Floras für Haus und Weißenbach 2 | 20 2 FRAKTIONEN SEPTEMBER 2020 das ganze Gemeindegebiet abgefahren ren. Wir in Haus sind sehr glücklich, und habe mich erkundigt, welche Arbei- dass Sie den Hauser Golfplatz so toll ten notwendig sind und erledigt werden betreiben. müssen. Hans Pürstl hat alles dokumen- tiert und ich werde dies nun, wie es unsere Finanzsituation zulässt, erledigen lassen. Nicht erfreulich ist, dass wir heuer weniger Einnahmen in unserer Gemein- Bürgermeister dekasse verzeichnen dürfen. Durch Coro- Stefan Knapp na haben sich die Kommunalsteuer und Ertragsanteile um ca. € 300.000.- verrin- Gratulation zur „Besten österreichi- Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen und gert. Somit sind wir gezwungen, einige schen Sommer-Bergbahn“. Deine Ini- Gemeindebürger, liebe Jugend! Vorhaben auf das nächste Jahr zu ver- tiative, lieber Herr GF Klaus Hofstätter, schieben. den Berg im Sommer täglich mit dem tol- Veränderung schafft Hoffnung, sie Ich habe mich entschieden ei- len touristischen Sommerangebot zu öff- macht manchmal auch Reibung not- nen neuen, unabhängigen, neutralen nen, war genial. Danke dafür. Die Hauser wendig, Veränderung schafft Chancen Bausachverständigen zu bestellen. Liebe Kaibling Seilbahn wurde mit dem Güte- und mancherorts auch Unsicherheit. Sie Hauserinnen und Hauser, Frau DI Caro- siegel „Beste österreichische Sommer- ist etwas, worüber man auch oft unter- line Rodlauer wird zukünftig Ihre Bau- Bergbahn“ ausgezeichnet. Ich gratulie- schiedlicher Meinung sein kann. Aber vorhaben begleiten. Sie konnte sich bei re GF Klaus Hofstätter und seinem Team Veränderung ist nichts, was sich auf- ihren ersten Einsätzen bereits positiv ganz herzlich zu dieser verdienten Güte- halten lässt. -

Busfahrplan 2018 Bus Timetables

Sommer Busfahrplan 2018 Bus timetables 960: Schladming – Ramsau am Dachstein – Dachstein Gletscherbahn 962+964: Silberkarklamm – Vorberg – Ramsau am Dachstein – Filzmoos* 972-974: Schladming – Rohrmoos/Hochwurzen – Untertal/Obertal/Preuneggtal Wanderbus Schladming – Haus im Ennstal – Steirischer Bodensee 965A+B: Citybus Schladming – Untere Klaus/Obere Klaus 8605: Ramsau am Dachstein – Pichl-Vorberg – Reiteralm/Preunegg Jet 900/902: Gröbming – Aich – Haus im Ennstal – Schladming – Mandling* 945+946: Gröbming – Stein an der Enns – Kleinsölk/Großsölk Kostenlos mit Sommercard * ausgenommen Linien 900 und 902, sowie Linie 962 ab Dachsteinruhe bis Filzmoos 2018_Inserat-Sommercard_105x210.pdf 1 19.04.2018 12:56:48 EINZIGARTIG über 100 Top-Erlebnisse inklusive und über 100 extra Bonusleistungen * bei einem unserer über 1.000 Sommercardgastgeber DEIN FREIER Z UTRITT SCHLADMING-DACHSTEIN SOMMERCARD DA STECKT MEHR DRIN! Für Dich ganz ohne Aufpreis mit dabei! Mit der Sommercard erhältst Du freien Eintritt in über 100 Top-Freizeitattraktio- nen und bis zu 50 % Ermäßigung bei über 100 Bonuspartnern. Und das Beste ist: Die Sommercard gibt es für Dich kostenlos bereits ab einer Übernachtung bei einem unserer über 1.000 Sommercardgastgeber – gültig inklusive An- und Abreisetag. Natürlich erhält Dein Kind seine eigene KidsCard – und alle Urlaubsträume werden wahr. ARGE Schladming-Dachstein Card 8970 Schladming, Ramsauerstraße 756 • +43 (0) 3687/23310 [email protected], www.sommercard.info Inhalt 960 | Schladming – Dachstein Seilbahn ........................................... -

SD Wandern Subfolder 2017 D RZ.Indd

Premium-Wanderregion & Steirische Gastfreundschaft Saftige Alpentäler, prächtige Berggipfel, klare Bäche und saubere Luft – herzliche Grüße aus den erfrischenden Landschaften der Urlaubsregion Schladming-Dachstein. Als eine der Top Skiregionen Österreichs bekannt, wandelt sich die Urlaubsregion Schladming-Dachstein im Sommer zu einer Premium-Wanderregion. Es erwarten Dich ursprüngliche Landschaften, grüne Alpentäler, die prächtigen Kalkwände des vergletscherten Dachsteins und unzählige Gipfel mitsamt den 300 Bergseen der Schladminger Tauern. Egal ob Du das sanfte Naturerlebnis bevorzugst oder Dich die großen Gipfel locken – sicher findest Du bei 1.000 km Wanderwegen in der Region Schladming-Dachstein »Deinen persönlichen Lieblingsweg«. Hütten- & Schutzhütten mit Persönliche Beratung Übernachtungsmöglichkeit Unsere Mitarbeiter in den 7 Infobüros beraten Dich gerne auch über die kostenlos geführten Wanderungen in den ein- zelnen Orten. Schladming Gröbminger Land Preintalerhütte 0664/1448881 Gasthof Steinerhaus 03686/2646 Alle Informationen und noch vieles mehr findest Du unter www.schladming-dachstein.at/wandern Waldhornalm 03687/61475 Stoderhütte 03686/21071 Gollinghütte 0676/5336288 Galsterbergalmhütte 0676/9518228 Keinprechthütte 0664/4330346 Ritzingerhütte 0676/9459817 Duisitzkarseehütte 0664/9733684 Michaelerberghaus 03685/22566 Fahrlechhütte 0664/3385903 Grimming-Donnersbachtal Ignaz-Mattis-Hütte 0664/4233823 Mörsbachwirt 03680/211 Dankelmayrhütte 03683/2246 Unsere Sommerbergbahnen Alpin- & Bergführer Giglachseehütte 0664/9088188 -

Alps Residence Holidayservice Informationsmappe

Alps Residence Holidayservice Informationsmappe Alps Residence Holidayservice GmbH Ennsling 164 A- 8967 Haus im Ennstal Telefon: +43 660 440 88 34 [email protected] www.alps-residence.com Inhaltsverzeichnis. Table of contents Allgemeine Informationen. General Information Hinweise zur Abreise. Check Out Information Kontaktdaten. Contact Details Winteraktivitäten. Winter Activities Über Alps Residence. About Alps Residence Bergresort Hauser Kaibling T: +43 660 440 88 34 - 1 - Herzlich willkommen. Welcome. Liebe Gäste, schön, Sie in unserem Bergresort Hauser Kaibling in Haus begrüßen zu dürfen! Wir hoffen, Sie verbringen erholsame Urlaubstage in „Österreichs grünem Herzen“, der Steiermark, und genießen Ihre Zeit bei Alps Residence. Damit Sie sich bei uns von Beginn an wohlfühlen, haben wir Ihnen auf den nächsten Seiten einige hilfreiche Informationen zusammengestellt. Sie haben noch Fragen zu Ihrem Aufenthalt, Ihrem Appartement oder Chalet oder Ihrer Urlaubsregion? Das Rezeptionsteam von Alps Residence Holidayservice steht Ihnen an der Rezeption natürlich gerne persönlich sowie telefonisch zur Verfügung: Montag bis Sonntag von 8:00 bis 18:00 Uhr Dear guest We are very pleased to welcome you at Bergresort Hauser Kaibling. We hope you will spend relaxing holidays in our beautiful region and enjoy your time with Alps Residence. In this map, we compiled you some helpful information about the region, tourist activities and other helpful information to make your stay easier. For any further information, questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact our reception team at the front desk. We will be happy to assist you! Opening hours front desk: daily from 8.00 am to 06.00 pm and by telephone. -

„Herzlich Willkommen

Herzlich willkommen «««« „ Steirerhof WANDER-VITALHOTEL WANDERPARADIES Zauberhafte Spiegelungen im DACHSTEIN TAUERN Duisitzkarsee bewundern. Gemütliche oder anspruchsvolle Wandertouren, Hütteneinkehr mit regionalen Köstlich- keiten aus der Steiermark, erfrischend klare Bergseen, auf Klettersteigen unterwegs oder ganz einfach Spazierengehen durch Wälder oder entlang eines Baches. Ein Wanderurlaub in Österreich ist eine Reise zu sich selbst! Wanderungen mit herrlichem Panorama-Blick inmitten des Ramsauer Hochplateaus, den Dachstein-Gletscher und den Schladminger Tauern. Bei uns erwarten Sie einzigar- tige Erlebnisse in der Natur. Schöne Landschaften, Stille genießen, genussvolles Essen „ und kompetente wanderfreudige Gastgeber – das ist Wanderurlaub mit Genuss. Sie wohnen in einem familiengeführten Hotel in einer der schönsten Naturlandschaften. Unsere Region bietet ca. 850 km Wanderwege für Naturliebhaber und anspruchs- volle Bergsteiger und Wanderer. Wanderwege und ausgeschilderte Nordic Walking Strecken befinden sich direkt vor der Haustür. Öffentliche Wanderbusse verkehren regelmäßig ab Hotel zu den beliebtesten Ausflugszielen. Wir sind Sommercard Partner der Region Jeder unserer Schladming-Dachstein. Für unsere Gäste bedeutet .. .. dies, dass Sie von Mai bis Oktober bei Ihrer Ankunft Gaste erhalt die Sommer-Card für die gesamte Dauer Ihres Auf- EIN AUSZUG DER SOMMERCARD INKLUSIV-LEISTUNGEN: enthaltes erhalten. Dachstein Gletscherbahn · Gipfelbahn Hochwurzen – Rohrmoos · Planai Seilbahn – Schladming die Sommercard. Ursprungstraße · -

5 Costs of Municipal Waste Management

Seite 2 l L-AWP 2010 Provincial Waste Management Plan Styria 2010 unanimously agreed by the Styrian Provincial Government 17 May 2010 Volume 17 of information series Waste and Material Flow Management Owner and editor: Styrian Provincial Government Specialised Division 19D – Waste and Material Flow Management 8010 Graz, Bürgergasse 5a AUSTRIA Phone: +43 (0)316 877-4323 Fax: +43 (0)316 877-2416 Email: [email protected] Head: Hofrat Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Wilhelm Himmel (Sustainability Coordinator) Project management and compilation: Mag. Dr. Ingrid Winter (FA19D) Phone: +43 (0)316 877-5931 Email: [email protected] Picture copyright: FA19D Data source Styria maps: Styrian Provincial Government, Abteilungsgruppe Landesbaudirektion – Stabsstelle Geoinformation (LBD-GI) English version: FA19D FA19D 50.01-05/2008-059-4 1.12.2010 Translation: Mag. Claudia Lanschützer Note for citation: Styrian Provincial Government (ed.): Federal Waste Management Plan 2010. Graz, 2010. The L-AWP 2010 is available for download in PDF format at www.abfallwirtschaft.steiermark.at. Seite 4 l L-AWP 2010 – Preface Preface Natural resources – notably water, food and energy – are the central issues to be dealt with in the 21st century. This means that i) we have to find more economic and more efficient ways to use our resources; ii) we have to strengthen regional economic structures and iii) we have to change our life-style. If we fail to use our resources in an efficient way, the cost of our living will literally outgrow our expectations. While natural resources are limited, the number of people is growing, and so is the consumption of nature and its resources. -

Hochwasser- Risikomanagementpläne

HOCHWASSER- RISIKOMANAGEMENTPLÄNE STEIERMARK INHALT Hochwasserrisikomanagementpläne - Was sind sie? 2 Impressum 10 Fragen und Antworten für einen Gesamtüberblick Johann Seitinger Medieninhaber und Herausgeber AMT DER STEIERMÄRKISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Wie entstehen Hochwasserrisikomanagementpläne? 5 Abteilung 14 Wasserwirtschaft, Ressourcen und Nachhaltigkeit Eine Infografik erklärt ... Wartingergasse 43, 8010 Graz Hochwasserrisikogebiete 7 Text, Redaktion und Gestaltung Welche gibt es in der Steiermark? Wo liegen sie? RIOCOM - Ingenieurbüro für Kulturtechnik und Wasserwirtschaft Mag. Cornelia Jöbstl, DI Albert Schwingshandl Welche primären Maßnahmenbündel sind für sie vorgesehen? Marienplatz 1, 8020 Graz Hochwassergefahren- und -risikokarten 11 Bildquellen Risikogebiet Leoben: Freisinger / Stadt Leoben Sie geben Auskunft über das Hochwasserrisiko Hochwasser 2011, Wölzerbach, Bezirk Murau: Bereichsfeuerwehrverband Murau Hochwasser 2002, Ennstal: Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung, Baubezirksleitung Liezen Hochwasser Mai 2013, RHB Schöckelbach, Weinitzen: Stadt Graz, Abteilung für Grünraum und Gewässer Maßnahmenkatalog 13 Beteiligungsprozess in der Erstellung der HWRMP: RIOCOM Welche Maßnahmen umfassen die Hochwasserrisikomanage- mentpäne? Lektorat DI Rudolf Hornich, Ing. Christoph Schlacher MSc Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung Ergebnisse der steirischen Hochwasser- 14 Abteilung 14 Wasserwirtschaft, Ressourcen und Nachhaltigkeit Wartingergasse 43, 8010 Graz risikomanagementpläne Vorsorge, Schutz, Bewusstsein, Vorbereitung, Nachsorge -

Spezielle Nutzungsbestimmungen Des Rail&Fly-Boarding Pass Conditions of Use of the Rail&Fly-Boarding Pass To/From Graz B

Spezielle Nutzungsbestimmungen des rail&fly-boarding pass Conditions of use of the rail&fly-boarding pass To/from Graz Benützbare Züge / Available trains Gültig in allen von ÖBB geführten Zügen, ausgenommen Nachtzüge (Kategorie EN). Valid on all trains operated by ÖBB, except night-service (category EN). Altersgrenzen / Age limits Es gelten die Altersgrenze des Flugverkehrs. Age limits of air transport are applied. Kleinkind / Infant: unter 2 Jahre / under 2 years Kinder / Child: 2 bis unter 12 Jahre / 2 up till 12 years Erwachsene /adults: ab 12 Jahre / 12 years and older Erweiterte Gültigkeit des rail&fly-boarding pass Extended reach (validity) of the rail&fly-boarding pass Der rail&fly-boarding pass nach/von Flughafen Wien von/nach Graz Hbf kann alternativ auch zu folgenden Stationen genutzt werden: The rail&fly-boarding pass to/from Vienna Airport from/to Graz Hbf can alternatively be used to the following stations: Admont Graz Don Bosco Kraubath/Mur Purkla Aich-Assach Graz Hbf Krieglach Raaba Allerheiligen-Mürzhofen Graz Liebenau Murpark Langenwang/Mürz Rohr/Raab Ardning Graz Ostbahnhof-Messe Laßnitzhöhe Rohrbach-Vorau Bad Aussee Graz Puntigam Laßnitzthal Scheifling in Stmk Bad Blumau Gröbming Lebring Schladming Bad Mitterndorf Gstatterboden im Leibnitz Schwarza b.Spielfeld Nationalpark Bad Mitterndorf-Heilbrunn Leoben Hbf Sebersdorf Halbenrain Bad Radkersburg Lichendorf b.Mureck Selzthal Hart b.Graz Bad Waltersdorf Liezen Söchau Hartberg Bierbaum/Safen Lödersdorf Spielfeld-Straß Hatzendorf Bruck/Mur Marein-St.Lorenzen Spital am -

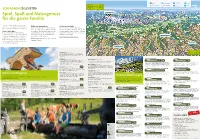

SD Familien Subfolder 2018 D RZ.Indd

N Gondelbahn Infobüros Alpine Wasserwelten i mit Sommerbetrieb Badeseen Radstadt 10 Minuten Sessellift ˘ r Aussichtsreiche Gipfel Markante Berggipfel Freibäder W O ˘ Tauernautobahn 15 Minuten mit Sommerbetrieb ˘ Salzburg 60 Minuten ˘ München 2,5 Stunden S Dachsteingletscher Bad Ischl Bischofsmütze Pyhrnpass Hoher Dachstein Bad Aussee 2430 Grimming Torstein 2996 Spiel, Spaß und Naturgenuss 2351 r Mitterspitz Grimming r Hoher r Krippenstein r Wörschach 2109 Kammspitze Liezen 2139 Röthelstein Stoderzinken Trautenfels für die ganze Familie 2247 Scheichenspitze 2048 r 2667 r St. Martin/Grimming Aigen im Ennstal Irdning i Gröbming i Mitterberg Niederöblarn Hochrettelstein Die Steirische Gastfreundschaft macht uns zu richtigen Donnersbach 2220 Familien-Profis – von behaglichen Unterkünften über vor- Ein Tag ohne Mama und Papa Erstklassige Unterkünfte Ramsau am Dachstein i Öblarn i r Stein/Enns i Walchental Freiräume für Eltern und fröhliche Abwechslung für Egal ob Kinderhotel, komfortable Ferienwohnungen Rittisberg r Aich i Pruggern i Planneralm zügliche Restaurants bis zu speziellen Kinderprogrammen. 1500 Gumpeneck 2226 Kinder – das ermöglicht unser teilweise betreutes Wo- oder stilechter Familienurlaub am Bauernhof – die Ent- Haus im Ennstal Mandling i Michaelerberg Großsölk r chenprogramm. Von Montag bis Freitag bieten unsere scheidung liegt bei Dir. Unsere gepflegten Unterkünfte Gössenberg Großsölktal Urlaub in vitaler Natur Donnersbachwald i Natur ist nicht nur Kulisse sondern ein aktiver Orte Kinder-Programme, die begeistern. Und wo die