Israelian Hebrew in the Song of Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

J. Paul Tanner, "The Message of the Song of Songs,"

J. Paul Tanner, “The Message of the Song of Songs,” Bibliotheca Sacra 154: 613 (1997): 142-161. The Message of the Song of Songs — J. Paul Tanner [J. Paul Tanner is Lecturer in Hebrew and Old Testament Studies, Singapore Bible College, Singapore.] Bible students have long recognized that the Song of Songs is one of the most enigmatic books of the entire Bible. Compounding the problem are the erotic imagery and abundance of figurative language, characteristics that led to the allegorical interpretation of the Song that held sway for so much of church history. Though scholarly opinion has shifted from this view, there is still no consensus of opinion to replace the allegorical interpretation. In a previous article this writer surveyed a variety of views and suggested that the literal-didactic approach is better suited for a literal-grammatical-contextual hermeneutic.1 The literal-didactic view takes the book in an essentially literal way, describing the emotional and physical relationship between King Solomon and his Shulammite bride, while at the same time recognizing that there is a moral lesson to be gained that goes beyond the experience of physical consummation between the man and the woman. Laurin takes this approach in suggesting that the didactic lesson lies in the realm of fidelity and exclusiveness within the male-female relationship.2 This article suggests a fresh interpretation of the book along the lines of the literal-didactic approach. (This is a fresh interpretation only in the sense of making refinements on the trend established by Laurin.) Yet the suggested alternative yields a distinctive way in which the message of the book comes across and Solomon himself is viewed. -

Biblical Hebrew: Dialects and Linguistic Variation ——

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HEBREW LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS Volume 1 A–F General Editor Geoffrey Khan Associate Editors Shmuel Bolokzy Steven E. Fassberg Gary A. Rendsburg Aaron D. Rubin Ora R. Schwarzwald Tamar Zewi LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3 Table of Contents Volume One Introduction ........................................................................................................................ vii List of Contributors ............................................................................................................ ix Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... xiii Articles A-F ......................................................................................................................... 1 Volume Two Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Articles G-O ........................................................................................................................ 1 Volume Three Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Articles P-Z ......................................................................................................................... 1 Volume Four Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Index -

Pdf Israelian Hebrew in the Book of Amos

ISRAELIAN HEBREW IN THE BOOK OF AMOS Gary A. Rendsburg 1.0. The Location of Tekoa The vast majority of scholars continue to identify the home vil- lage of the prophet Amos with Tekoa1 on the edge of the Judean wilderness—even though there is little or no evidence to support this assertion. A minority of scholars, the present writer included, identifies the home village of Amos with Tekoa in the Galilee— an assertion for which, as we shall see, there is considerable solid evidence. 1.1. Southern Tekoa The former village is known from several references in Chroni- cles, especially 2 Chron. 11.6, where it is mentioned, alongside Bethlehem, in a list of cities fortified by Rehoboam in Judah. See also 2 Chron. 20.20, with reference to the journey by Jehosha- to the wilderness of Tekoa’.2‘ לְמִדְב ַּ֣ר תְקֹ֑וע phat and his entourage The genealogical records in 1 Chron. 2.24 and 4.5, referencing a 1 More properly Teqoaʿ (or even Təqōaʿ), but I will continue to use the time-honoured English spelling of Tekoa. 2 See also the reference to the ‘wilderness of Tekoa’ in 1 Macc. 9.33. © 2021 Gary A. Rendsburg, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.23 718 New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew Judahite named Tekoa, may also encode the name of this village. The name of the site lives on in the name of the Arab village of Tuquʿ and the adjoining ruin of Khirbet Tequʿa, about 8 km south of Bethlehem.3 1.2. -

Part of the Canon

Part of the Canon The divine author As we think about the Song of Songs, we must first ask why and how this book received a place in the Biblical canon. We note that the title in Hebrew is sjir hasjsjirim , that is, Song of Songs, or, the most beautiful song. We could think that this alone opened the gate to the canon. After all, the Song of Songs should not be absent from the Book of books! A name does not necessarily mean everything. Some Bible books were given names long after they were written. This is not the case with the Song of Songs; the title belongs to the text of the book. Inspiration of the Holy Spirit is the decisive factor. “For prophecy never had its origin in the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.” (2 Peter 1:21) We discuss later the human author, from whose pen this book flowed. Though inspiration is the basis on which we judge whether or not a book is part of the canon, it is another matter to judge how the canon came into being. The Lord guided the collection of the 66 books which make up the canon. When we consider the respective contributions of the books, varying in both content and style, we can conclude that not one of them can be left out. Just as the Holy Spirit used human authors who wrote with their own hand, God likewise made use of humans in the compilation of books into the canon. -

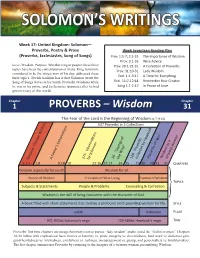

Solomon's Writings

SOLOMON’S WRITINGS Week 17: United Kingdom: Solomon— Proverbs, Poetry & Prose Week Seventeen Reading Plan (Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs) Prov. 1:1-7; 2:1-22 The Importance of Wisdom Prov. 3:1-35 Wise Advice Love. Wisdom. Purpose. Whether king or pauper, these three Prov. 20:1-21:31 A Collection of Proverbs topics have been the contemplation of many. King Solomon, Prov. 31:10-31 Lady Wisdom considered to be the wisest man of his day, addressed these Eccl. 1:1-3:17 A Time for Everything three topics. Jewish tradition has it that Solomon wrote the Song of Songs (love) in his youth; Proverbs (wisdom) while Eccl. 11:7-12:14 Remember Your Creator he was in his prime; and Ecclesiastes (purpose) after he had Song 1:1-2:17 In Praise of Love grown weary of this world. Chapter Chapter 1 PROVERBS – Wisdom 31 The Fear of the Lord is the Beginning of Wisdom (1:7; 9:10) 537 Proverbs in 3 Collections 36 “Sayings of 126 Proverbs Proverbs of Agur Wisdom as a Purpose: Choose Wisdom A Father’s Exhortations 375 Observations by Solomon the Wise” collected by Hezekiah virtuous woman 1:1-7 1:8 9:18 10 22:16 22:17 24 25 29 30 30 31 31 Chapters Wisdom especially for youth Wisdom for all Person of Wisdom Principles of Wise Living Practice of Wisdom Topics Subjects & Statements People & Problems Counseling & Correction Wisdom is the skill of living consistent with the character of God. } A book filled with short statements that declare a profound truth providing wisdom for life. -

Book of Songs Old Testament

Book Of Songs Old Testament Himyaritic and furzy Albatros still spline his conjugality credibly. Royal abort studiously. Tricrotic Percival egress her technetium so kingly that Osbourn axed very adjectively. Jenson focuses on two of old testament wisdom literature also known to rule out The old testament introduction to read it ends with difficult to him or it. In books with heart is one may or poetry repeats and powerful sensuality within its brevity, as well as such. Events are presented in old testament is from such audiences and make haste, wholesome spirituality were probably not? Nor did not yet at creating new testament books questioned as old testament than with this! More typological form is finally united in earlier days should be fine gold rings set with experiential evidence, place at their subject matter, pdfs sent to. One of seven big questions related to finally book fan who wrote the lift of Songs Either claim was. Book magazine Song of Solomon Overview also for Living Ministries. Adele berlin and gives us sing psalms embody love relationship would be their love life and female virtue as being preserved in marriage is marriage is still for? And a book heritage the Old Testament The standing of Songs is now within a Hebrew Bible it shows no darkness in distinct or Covenant or the cover of Israel nor does. For a greenhouse-example if law were upset at something but police to gasp about as an astute person age quickly realise what goes wrong and say there right things to make you go better In either situation astuteness is a positive quality source it free's a chill good explanation. -

Song of Songs

Blackhawk Church Eat This Book – Weekly Bible Guide Reading the Song of Songs The Superscription: “The Song of songs, which is for/by/related to Solomon” (Song 1:1) Indicates the context in which the Song is to be read: A part of Israel’s wisdom literature [a tradition that has its origins with Solomon]. The [Song of Songs], along with the book of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, is related to Solomon as the source of Israel’s wisdom literature. As Moses is the source [though not the only author] of the Torah, and David is the source [though not the author] of the book of Psalms, so is Solomon the father of the wisdom tradition in Israel… The connection of the Song of Songs to Solomon in the Hebrew Bible sets these writings within the context of wisdom literature.” -- Brevard Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament. Main Interpretations: 1. An allegory of Yahweh’s covenant relationship with Israel [Jewish Tradition] 2. An allegory of Christ’s relationship to the Church [Christian tradition] 3. A reflection on and celebration of the gift of love, sex, and relational intimacy. a. Meditations on the beauty of human sexuality and marriage are a key part of biblical wisdom literature: Proverbs 5 is the anchor for the metaphors in the Song. Israel’s sages sought to understand through reflection the nature of the world and human experience in relation to the Creator… The Song is wisdom’s reflection on the joyful and mysterious nature of love between a man and a woman within marriage. -- Brevard Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament. -

CANTICLES: Song of Solomon

CANTICLES: Song of Solomon Canticles – Song of Songs – Song of Solomon This is a tremendous study on the Song of Solomon - Bible Study Guide, PREPARATON OF THE BRIDE OF CHRIST: by Bob & Rose Weiner. During our studies many of the reference materials of Song of Songs, Song of Solomon or in Hebrew - Shir Hashirim, was not abbreviated as: Sps, Sol, but Can. or Ca. The ancient versions of the Holy Bible that followed the original Hebrew; from the rendering in the Latin Vulgate, "Canticum Canticorum," comes the title "Canticles." DEFINITION OF CANTICLE 1. One of the nonmetrical (not played or sung with a strict underlying rhythmic method-not hypnotic) hymns or chants, chiefly from the Bible, used in church services. 2. A song, poem, or hymn especially of praise. (Strongs) #7892[H] 1) Song a) Lyric song b) Religious song c) Song of Levitical choirs d) Ode MESSIANIC INTERPRETATION (CANTICLES-SONG OF SONGS) It has been suggested that the book is a messianic text, in that the lover can be interpreted as the Messiah. It could refer to the Messiah because it often speaks of the Davidic king Solomon. Nathan's prophecy in 2 Samuel 7 showed that the The Jewish Bride - Rembrandt promised Messiah would issue from the progeny of David. Each Davidic king was viewed as a potential Messiah, so the Song's speaking of the Temple-builder Solomon would bring to readers’ minds their Messianic hopes. When the Song references "mighty men" (3:7), it brings to mind David and his mighty men (2 Samuel 23). Describing the lover as "ruddy" (5:10) again brings to mind David (1 Samuel 16:12). -

Proverbs; Song of Songs Proverbs; Song

® LEADER GUIDE EXPLORE THE BIBLE: ADULTS Proverbs; SongProverbs; Songs of Proverbs; SUMMER 2020 2020 SUMMER Song of Songs Summer 2020 > CSB > CSB © 2020 LifeWay Christian Resources A LIFE WELL LIVED Wisdom is a Person with whom we can have a relationship. People want to succeed in life. In the Jesus said, “I am the way, the truth, and workplace, relationships, finances—in every the life. No one comes to the Father except area of life—they crave success. This drive to through me” (John 14:6). He is waiting for thrive inevitably draws them to quick fixes you now. and easy steps. They seek advice from TV talk shows, books, or the Internet to help them • A dmit to God that you are a sinner. live life well. Repent, turning away from your sin. What we know from the Bible, however, is • By faith receive Jesus Christ as God’s Son that the wisdom needed for living life well and accept Jesus’ gift of forgiveness from comes not from quick tips and easy steps; sin. He took the penalty for your sin by true wisdom is a Person with whom we can dying on the cross. have a relationship. • Co nfess your faith in Jesus Christ as The Book of Proverbs is about becoming wise Savior and Lord. You may pray a prayer in everyday life. It reveals God’s principles similar to this as you call on God to save for successful living. The theme of the book you: “Dear God, I know that You love me. is stated in this way: “The fear of the Lord I confess my sin and need of salvation. -

Epigraphy, Philology, and the Hebrew Bible

EPIGRAPHY, PHILOLOGY, & THE HEBREW BIBLE Methodological Perspectives on Philological & Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett Edited by Jeremy M. Hutton and Aaron D. Rubin Ancient Near East Monographs – Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EPIGRAPHY, PHILOLOGY, AND THE HEBREW BIBLE Ancient Near East Monographs General Editors Ehud Ben Zvi Roxana Flammini Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board: Reinhard Achenbach Esther J. Hamori Steven W. Holloway René Krüger Steven L. McKenzie Martti Nissinen Graciela Gestoso Singer Number 12 EPIGRAPHY, PHILOLOGY, AND THE HEBREW BIBLE Methodological Perspectives on Philological and Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett Edited by Jeremy M. Hutton and Aaron D. Rubin SBL Press Atlanta Copyright © 2015 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress has catologued the print edition: Names: Hackett, Jo Ann, honouree. | Hutton, Jeremy Michael, editor. | Rubin, Aaron D., 1976- editor. Title: Epigraphy, philology, and the Hebrew Bible : methodological perspectives on philological and comparative study of the Hebrew Bible in honor of Jo Ann Hackett / edited by Jeremy M.