The Bronze Statuette of a Mouse from Kedesh and Its Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Art in Motion Studies in Honour of Sir John Boardman On the Occasion of His 90Th Birthday

Greek Art in Motion Studies in honour of Sir John Boardman on the occasion of his 90th birthday edited by Rui Morais, Delfim Leão, Diana Rodríguez Pérez with Daniela Ferreira Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2019. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78969 023 1 ISBN 978 1 78969 024 8 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2019 Cover: Head of Alexander in profile. Tourmaline intaglio, 25 x 25 mm, Ashmolean (1892.1499) G.J. Chester Bequest. Photo: C. Wagner. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2019. Contents Preface ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 John Boardman and Greek Sculpture �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Olga Palagia Sanctuaries and the Hellenistic Polis: An Architectural Approach �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������14 Milena Melfi ‘Even the fragments, however, merit scrutiny’: Ancient -

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

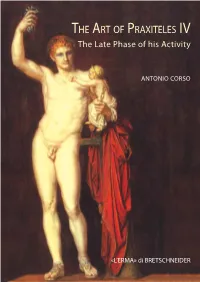

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

Mechanical Miracles: Automata in Ancient Greek Religion

Mechanical Miracles: Automata in Ancient Greek Religion Tatiana Bur A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, University of Sydney Supervisor: Professor Eric Csapo March, 2016 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Tatiana Bur, March 2016. Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... 1 A NOTE TO THE READER ................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 3 PART I: THINKING ABOUT AUTOMATION .......................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1/ ELIMINATING THE BLOCAGE: ANCIENT AUTOMATA IN MODERN SCHOLARSHIP ................. 10 CHAPTER 2/ INVENTING AUTOMATION: AUTOMATA IN THE ANCIENT GREEK IMAGINATION ................. 24 PART II: AUTOMATA IN CONTEXT ................................................................................... 59 CHAPTER 3/ PROCESSIONAL AUTOMATA ................................................................................ -

Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 2 | 1989 Varia Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena Ioannis Loucas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.242 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1989 Number of pages: 97-104 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Ioannis Loucas, « Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena », Kernos [Online], 2 | 1989, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.242 Kernos Kernos, 2 (1989), p. 97-104. RITUAL SURPRISE AND TERROR INANCIENT GREEK POSSESSION·DROMENA The daduch of the Eleusinian mysteries Themistokles, descendant of the great Athenian citizen of the 5th century RC'!, is honoured by a decree of 20/19 RC.2 for «he not only exhibits a manner of life worthy of the greatest honour but by the superiority of his service as daduch increases the solemnity and dignity of the cult; thereby the magnificence of the Mysteries is considered by all men to be ofmuch greater excitement (ekplexis) and to have its proper adornment»3. P. Roussel4, followed by K. Clinton5, points out the importance of excitement or surprise (in Greek : ekplexis) in the Mysteries quoting analogous passages from the Eleusinian Oration of Aristides6 and the Platonic Theology ofProclus7, both writers of the Roman times. ln Greek literature one of the earlier cases of terror connected to any cult is that of the terror-stricken priestess ofApollo coming out from the shrine of Delphes in the tragedy Eumenides8 by Aeschylus of Eleusis : Ah ! Horrors, horrors, dire to speak or see, From Loxias' chamber drive me reeling back. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The Masters of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus Antonio Corso Kanellopoulos Foundation / Messenian Society, Psaromilingou 33, GR10553, Athens, Greece, phone +306939923573,[email protected] The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is one of the most renowned monuments of the ancient world.1 Mausolus must have decided to set up his monumental tomb in the centre of his newly built capital toward the end of his life: he died in 353 BC.2 After his death, some writers who were renowned in the oratory – Theopompus, Theodectes, Naucrates and less certainly Isocrates – went to the Hecatomnid court at Halicarnassus and took part in the competition held in the capital of Caria in order to deliver the most convincing oration on the death of Mausolus. The agon was won by Theopompus.3 Poets had also been invited on the same occasion.4 After the death of this satrap, the Mausoleum was continued by his wife and successor Artemisia (353-351 BC) and finished after her death,5 thus during the rule of Ada and Idrieus (351-344 BC). The shape of the building is known only generically thanks to the detailed description of the monument given by Pliny 36. 30-31 as well as to surviving elements of the tomb. The Mausoleum was composed of a rectangular podium containing the tomb of the satrap, above which there was a temple-like structure endowed with a peristasis, which was topped by a pyramidal roof, made of steps and supporting a marble quadriga. The architects who had been responsible of the Mausoleum were Satyrus and Pytheus, who also wrote a treatise ‘About the Mausoleum’ (Vitruvius 7, praef. -

GREEK RELIGION Walter Burkert

GREEK RELIGION Walter Burkert Translated by John Raffan r Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts THINGS’ ANIMAL SACRIFICE II t . I ‘WORKING SACRED 55 diverted activity for the apathy which remains transfixed in reality; it lays claim to the highest seriousness, to the absolute. II When considered from the point of view of the goal, ritual behaviour appears as magic. For a science of religion which regards only instrumental 4 since acts action as meaningful, magic must be seen as the origin of religion, Ritual and Sanctuary which seek to achieve a given goal in an unclear but direct way are magical. The goal then appears to be the attainment of all desirable boons and the elimination of possible impediments: there is rain magic, fertility magic, love magic, and destructive magic. The conception of ritual as a kind of language, however, leads beyond this constraining artifice; magic is present only insofar as ritual is consciously placed in the service of some end — which may then undoubtedly affect the form of the ritual. Religious ritual is given as a collective institution; the individual participates within the framework of social communication, with the strongest motivating force being the need not in the study of religion which came to be generally acknowledged to stand apart. Conscious magic is a matter for individuals, for the few, and An insight are more important and end of the last century is that rituals is developed accordingly into a highly complicated pseudo-science. In early towards the ancient religions than are instructive for the understanding of the Greece, where the cult belongs in the communal, public sphere, the more is no longer seen in myths.’ With this recognition, antiquity importance of magic is correspondingly minimal.