Fourth Century Head in Central Museum, Athens Author(S): E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

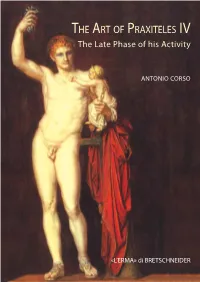

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The Masters of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus Antonio Corso Kanellopoulos Foundation / Messenian Society, Psaromilingou 33, GR10553, Athens, Greece, phone +306939923573,[email protected] The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is one of the most renowned monuments of the ancient world.1 Mausolus must have decided to set up his monumental tomb in the centre of his newly built capital toward the end of his life: he died in 353 BC.2 After his death, some writers who were renowned in the oratory – Theopompus, Theodectes, Naucrates and less certainly Isocrates – went to the Hecatomnid court at Halicarnassus and took part in the competition held in the capital of Caria in order to deliver the most convincing oration on the death of Mausolus. The agon was won by Theopompus.3 Poets had also been invited on the same occasion.4 After the death of this satrap, the Mausoleum was continued by his wife and successor Artemisia (353-351 BC) and finished after her death,5 thus during the rule of Ada and Idrieus (351-344 BC). The shape of the building is known only generically thanks to the detailed description of the monument given by Pliny 36. 30-31 as well as to surviving elements of the tomb. The Mausoleum was composed of a rectangular podium containing the tomb of the satrap, above which there was a temple-like structure endowed with a peristasis, which was topped by a pyramidal roof, made of steps and supporting a marble quadriga. The architects who had been responsible of the Mausoleum were Satyrus and Pytheus, who also wrote a treatise ‘About the Mausoleum’ (Vitruvius 7, praef. -

Complete Cast Gallery Listing

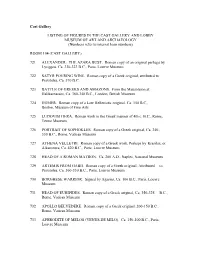

Cast Gallery LISTING OF FIGURES IN THE CAST GALLERY AND LOBBY MUSEUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY (Numbers refer to internal loan numbers) ROOM 104 (CAST GALLERY) 721 ALEXANDER: THE AZARA BUST. Roman copy of an original perhaps by Lysippos, Ca. 330-323 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 722 SATYR POURING WINE. Roman copy of a Greek original, attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 370 B.C. 723 BATTLE OF GREEKS AND AMAZONS. From the Mausoleion at Halikarnassos, Ca. 360-340 B.C., London, British Museum 724 HOMER. Roman copy of a Late Hellenistic original, Ca. 150 B.C., Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 725 LUDOVISI HERA. Roman work in the Greek manner of 4th c. B.C., Rome, Terme Museum 726 PORTRAIT OF SOPHOKLES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 340- 330 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 727 ATHENA VELLETRI. Roman copy of a Greek work, Perhaps by Kresilas, or Alkamenes, Ca. 420 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 728 HEAD OF A ROMAN MATRON. Ca. 200 A.D., Naples, National Museum 729 ARTEMIS FROM GABII. Roman copy of a Greek original, Attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 360-330 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 730 BORGHESE WARRIOR. Signed by Agasias, Ca. 100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 731 HEAD OF EURIPIDES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 350-325 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 732 APOLLO BELVEDERE. Roman copy of a Greek original, 200-150 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 733 APHRODITE OF MELOS (VENUS DE MILO). Ca. 150-100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 734 ZEUS BATTLING GIANTS. From the frieze of the Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon, Ca. -

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus Restored

' r=li=Ii=Ipdp=Jr=I(=Ji=Jr=Ji=li=Ji=Ir=lr=lr=lr=Jr=lf=J ' i i! THE MAUSOLEUM iQ !D in ! D ! " in :D i HALICARNASSUS D | D n D RESTORED. ^1 i r=Jr=Jr=iir=Jf=Jr=Jr=Jr=Jr==Jr=Jr=Jr=Jr=Jr=Ji^r=Jr=Jr^ a Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/mausoleumathalicOOferg THE MAUSOLEUM AT HALICAENASSUS RESTORED IN CONTOnMlTV WITH THE RECENTLY DISCOVERED REMAINS. BY JAMES FEllG USSON, FEI.IX)W noVAL INSTITUTE OK BRITISH AnClIITECTS. AUTHOR OF THK 'HANDDOOK OF ARCIIITECTUUE ;' 'ESSAY OS TIIK TOPO<5RAPIIY i>F JKIIUSAI.FM,' \c. LONDON: J 0 H N M U R R A Y, A L li I- M A R L E S T R K K T 18G2. The right r/ TratisM.oii is icsorcd. S, STAMFOnn STREET, PREFACE. The Essay contained in the following pages has no pretension to being a complete account of the Mausoleum at Ilahcarnassus. All that has been attempted in the present instance is to recapitulate and explain the various data wliich have recently been brought to light for restoring that celebrated monument of antiquity; and to show in wliat manner these may be applied so as to perfect a solution of the riddle wlnCli has so long perplexed tlie student of classical architecture. At some future period it may be worth while to go moie fully and with more careful elaboration into the whole subject; Init to do this as it should be done, would require more leisure and better opportunities than are at present at the Author's disjiosal for such a j)Ui-})ose. -

Greek Architecture

Cbautauqua "Reading Circle literature GREEK ARCHITECTURE P,Y T. ROGER SMITH, F. R. I. B. A. AND GREEK SCULPTURE BY GEORGE REDFORD, F. R. C. S. WITH AN" INTRODUCTION* HV WILLIAM H. GOODYEAR "CClitb /fcang 1f llustrations MKADYILI.K PI'.XNA KI.OOI) AM) \-INCKNT Cbe Chautauqtia.-Ccnturn press 1892 The required books of the C. L. S. C. are recommended by a Council of six. It must, however, be understood that recom- mendation does not involve an approval by the Council, or by any member of it, of every principle or doctrine con- tained in the book recommended. Published by arrangement with Sampson Low, Marston and Com- pany, Limited, London. The Chautauqua- Century Press, Meadvillc, Pa., U. &'. A. Electrotyped, Printed, and Bound by Flood & Vincent. sra URt PREFACE. customary discrimination and wisdom of the mana- THEgers of the Chuutauqua Literary and Scientific Circle are apparent in their choice of the compendiums on Greek architecture and Greek sculpture which are united in this book. Both are written by English scholars of distin- guished reputation. Both are written in a scientific spirit and in such manner as to supply much exact matter-of-fact infor- mation, without sacrificing popular quality. Some slight additions and corrections, made necessary by discoveries or by revisions of scientific opinion, dating since the original books were written, have been entered in an ap- pendix. My duty in the preparation of a preface is to point out, first, that this work on Greek architecture and sculpture is part of a course of reading on Greek history ["Grecian History," by James II. -

The Bronze Statuette of a Mouse from Kedesh and Its Significance

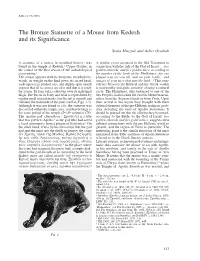

BABesch 76 (2001) The Bronze Statuette of a Mouse from Kedesh and its Significance Sonia Mucznik and Asher Ovadiah A statuette of a mouse in moulded bronze1 was A similar event occurred in the Old Testament in found in the temple at Kedesh,2 Upper Galilee, in connection with the Ark of the God of Israel: ... five the course of the first season of the archaeological golden emerods, and five golden mice, according to excavations.3 the number of the lords of the Phillistines: for one The mouse appears with its forepaws stretched for- plague was on you all, and on your lords... and wards, its weight on the hind paws; its raised head, images of your mice that mar the land...8 This coin- wide-open eyes, pricked ears, and slightly open mouth cidence between the Biblical and the Greek worlds suggest that all its senses are alert and that it is ready is noteworthy and quite amazing, closing a cultural for action. Its long tail is rolled up over its right hind cycle. The Philistines, who belonged to one of the thigh. The fur on its body and head is represented by Sea Peoples, had reached the eastern Mediterranean, regular small incised marks, but the tail is smooth and either from the Aegean islands or from Crete. Upon rounded; the underside of the paws are flat (Figs. 1-5). their arrival in the region they brought with them Although it was not found in situ, the statuette was cultural elements of the pre-Hellenic tradition, prob- discovered within the temple area, and thus belongs to ably including the mice of Apollo Smintheus. -

Some Old Masters of Greek Architecture

TROPHONIUS SLAYING AGAMEDES AT THE TREASURY OF IIYRIEUS. SOME OLD MAS- TERS OE GREEK ARCHITECTURE By HARRY DOUGLAS CURATOR OP * « « KELLOGG TERRACE PUBLISHED KT THE QURRTCR-OAK GREAT BARRINGTON, MASS., 1599 « * «* O COPIED Library of CaBgM , % Qfflco of the H*gl*t9r of Copyright* 54865 Copyright, 1899, By HARRY DOUGLAS. SECOND COPY. O EDWARD TRANCIS SCARLES WHOSE APPRECIATION OF THE HARMONIES OF ART, AND "WHOSE HIGH IDEALS OF ARCHITECTURE HAVE FOUND EXPRESSION IN MANY ENDURING FORMS, THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED. ^ PBEERCE Tub temptation to wander, with all the recklessness of an amateur, into the traditions of the best architec- ture, which necessarily could be found only in the his- tory of early Hellenic art, awakened in the author a desire to ascertain who were the individual artists primarily responsible for those architectural standards, which have been accepted without rival since their crea- tion. The search led to some surprise when it was found how little was known or recorded of them, and how great appeared to be the indifference in which they were held by nearly all the writers upon ancient art, as well as by their contemporary historians and biog- raphers. The author therefore has gone into the field of history, tradition and fable, with a basket on his arm, as it were, to cull some of the rare and obscure flowers of this artistic family, dropping into the basket also such facts directlv or indirectly associated with the VI PEEFACE. architects of ancient Greece, or their art, as interested him personally. The basket is here set down, contain- ing, if nothing more, at least a brief allusion to no less than eighty-two architects of antiquity. -

Another Note on the Sculpture of the Later Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

ANOTHER NOTE ON THE SCULPTURE OF THE LATER TEMPLE OF ARTEMIS AT EPHESUS. WHEN I wrote my former notes I was undecided as to the meaning of two of the sculptured fragments. No. 1215 is described in the Catalogue as ' Fragment of sculptured pier, with portions of two figures wrestling; one is half kneeling, and his left thigh is clasped by the hand of his opponent —perhaps the contest of Herakles and Antaeus.'1 (Fig. 1.) FIG. 1. The high relief shows that the fragment indeed belonged to a pedestal, and in re-examining it more carefully I find that a portion of the right-hand return still exists. Small as the trace is, it is enough to fix the place of the fragment in regard to the angle of the pedestal together with the vertical direction. It is plain, further, that the hand which grasps the leg is a left hand. These data are enough to define the general type of the design—a type which is well known for the struggle of Herakles and Antaeus (Fig. 2). The subject is that proposed in the Catalogue, but its treatment was not that which is there suggested. In Reinach's Repertoire four or five examples are illustrated of statue groups which conform to the same formula, and one is given in his collection of Reliefs (iii. p. 75). Another similar design from an engraved gem appears in Daremberg and Saglio's Dictionary under ' Antaeus.' Our Ephesus relief is by far the oldest of these, and in several other cases these sculptures give the earliest known versions of their subjects.