WHAT DID MYSTERIES MEAN to ANCIENT GREEKS? Nikolay P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

Cult of Isis

Interpreting Early Hellenistic Religion PAPERS AND MONOGRAPHS OF THE FINNISH INSTITUTE AT ATHENS VOL. III Petra Pakkanen INTERPRETING EARL Y HELLENISTIC RELIGION A Study Based on the Mystery Cult of Demeter and the Cult of Isis HELSINKI 1996 © Petra Pakkanen and Suomen Ateenan-instituutin saatiO (Foundation of the Finnish Institute at Athens) 1996 ISSN 1237-2684 ISBN 951-95295-4-3 Printed in Greece by D. Layias - E. Souvatzidakis S.A., Athens 1996 Cover: Portrait of a priest of Isis (middle of the 2nd to middle of the 1st cent. BC). American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations. Inv. no. S333. Photograph Craig Mauzy. Sale: Bookstore Tiedekirja, Kirkkokatu 14, FIN-00170 Helsinki, Finland Contents Acknowledgements I. Introduction 1. Problems 1 2. Cults Studied 2 3. Geographical Confines 3 4. Sources and an Evaluation of Sources 5 11. Methodology 1. Methodological Approach to the History of Religions 13 2. Discussion of Tenninology 19 3. Method for Studying Religious and Social Change 20 Ill. The Cults of Demeter and Isis in Early Hellenistic Athens - Changes in Religion 1. General Overview of the Religious Situation in Athens During the Early Hellenistic Period: Typology of Religious Cults 23 2. Cult of Demeter: Eleusinian Great Mysteries 29 3. Cult of Isis 47 Table 1 64 IV. Problem of the Mysteries 1. Definition of the Tenn 'Mysteries' 65 2. Aspects of the Mysteries 68 3. Mysteries in Athens During the Early Hellenistic Period and a Comparison to Those of Rome in the Third Century AD 71 4. Emergence of the Mysteries ofIsis in Greece 78 Table 2 83 V. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Resounding Mysteries: Sound and Silence in the Eleusinian Soundscape

Body bar (print) issn 2057–5823 and bar (online) issn 2057–5831 Religion Article Resounding mysteries: sound and silence in the Eleusinian soundscape Georgia Petridou Abstract The term ‘soundscape’, as coined by the Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer at the end of the 1960s, refers to the part of the acoustic environment that is per- ceivable by humans. This study attempts to reconstruct roughly the Eleusinian ‘soundscape’ (the words and the sounds made and heard, and those others who remained unheard) as participants in the Great Mysteries of the two Goddesses may have perceived it in the Classical and post-Classical periods. Unlike other mystery cults (e.g. the Cult of Cybele and Attis) whose soundscapes have been meticulously investigated, the soundscape of Eleusis has received relatively little attention, since the visual aspect of the Megala Mysteria of Demeter and Kore has for decades monopolised the scholarly attention. This study aims at putting things right on this front, and simultaneously look closely at the relational dynamic of the acoustic segment of Eleusis as it can be surmised from the work of well-known orators and philosophers of the first and second centuries ce. Keywords: Demeter; Eleusis; Kore; mysteries; silence; sound; soundscape Affiliation University of Liverpool, UK. email: [email protected] bar vol 2.1 2018 68–87 doi: https://doi.org/10.1558/bar.36485 ©2018, equinox publishing RESOUNDING MYSTERIES: SOUND AND SILENCE IN THE ELEUSINIAN SOUNDSCAPE 69 Sound, like breath, is experienced as a movement of coming and going, inspiration and expiration. If that is so, then we should say of the body, as it sings, hums, whistles or speaks, that it is ensounded. -

Sophocles' Philoctetes Roisman, Hanna M Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1997; 38, 2; Proquest Pg

The appropriation of a son: Sophocles' Philoctetes Roisman, Hanna M Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1997; 38, 2; ProQuest pg. 127 The Appropriation of a Son: Sophocles' Philoctetes Hanna M. Roisman ANHOOD in archaic and classical Greece-as in modern times-is generally manifested not so much in relation M ships with women as in relationships with other men, especially in the relationship between father and son. The Greek male is expected to produce sons who will continue his oikos (e.g. Soph. Ant. 641-45; Eur. Ale. 62lf, 654-57). Further, as Hesiod makes clear, sons should resemble their fathers in both looks and conduct, especially the latter (Op. 182,235; ef Ii. 6.476-81; Theophr. Char. 5.5). Such resemblance earns the father public esteem and proves his manliness; the lack of it may be cause for disparagement and calls his manliness into question. 1 We learn from Ajax and Philoctetes that Sophocles follows the Hesiodic imperative that sons should resemble their fathers in their natures and their accomplishments. Ajax sees himself as an unworthy son, having lost Achilles' arms to Odysseus, and prefers to commit suicide rather than face his father, Telamon, who took part in Heracles' expedition to Troy and got Hesione, the best part of the booty, as a reward (Aj. 430-40,462-65, 470ff, 1300-303; Diod. 4.32.5). At the same time, he expects his son, Eurysaces, to be like himself in nature, valor, and in everything else ('ttl.~' aA.A.' OIlOlO~, Aj. 545-51). Sophocles' Philoctetes, on the other hand, presents the strug gle between Odysseus and Philoctetes for the 'paternity' of Neoptolemus, as each tries to mold the young man in his own 1 Even in contemporary Greece the intense male rivalry for proving oneself takes place among men alone, while women and flocks serve as the object of this rivalry. -

STASIS in the POPULATION of METAPONTO: ANAYLSIS of ENVIRONMENT, HEALTH, and POLITICAL UNREST by Brittany Jean Viviani Submitted

STASIS IN THE POPULATION OF METAPONTO: ANAYLSIS OF ENVIRONMENT, HEALTH, AND POLITICAL UNREST By Brittany Jean Viviani Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Copyright © 2013 by Brittany Jean Viviani All rights reserved ii STASIS IN THE POPULATION OF METAPONTO: ANAYLSIS OF ENVIRONMENT, HEALTH, AND POLITICAL UNREST Brittany Jean Viviani, B.S. University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, 2013 The Greek colony of Metaponto offers an invaluable insight to the study of both rural and urban populations. Analysis of population is an important study to be able to examine social, political, and economic impacts of the time and how a group of people dealt with these stressors. Starting around 500 B.C. Metaponto experienced a period of great prosperity followed by a period of stasis starting around 425 B.C. Analysis was completed to understand whether stasis was the result of 1) epidemic disease, 2) environmental degradation, 3) political unrest, and 4) a combination of factors. Data used included archaeological data and historical accounts of Metaponto from Greek historians. Stress and possible warfare from different groups of people in the Mediterranean against Metaponto would have created increased tension within a colony already ravaged by disease. This could have caused the perfect storm to create stasis temporarily ending the period of prosperity. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. David Anderson and committee members Dr. Mark Chavalas, and Dr. Timothy McAndrews for all of their support and guidance during the writing process of my thesis. -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

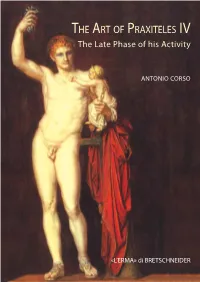

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins Coins were developed about 650 BC on the western coast of modern Turkey. From there, they quickly spread to the east and the west, and toward the end of the 5th century BC coins reached the Celtic tribes living in central Europe. Initially these tribes did not have much use for the new medium of exchange. They lived self-sufficient and produced everything needed for living themselves. The few things not producible on their homesteads were bartered with itinerant traders. The employ of money, especially of small change, is related to urban culture, where most of the inhabitants earn their living through trade or services. Only people not cultivating their own crop, grapes or flax, but buying bread at the bakery, wine at the tavern and garments at the dressmaker do need money. Because by means of money, work can directly be converted into goods or services. The Celts in central Europe presumably began using money in the course of the 4th century BC, and sometime during the 3rd century BC they started to mint their own coins. In the beginning the Celtic coins were mere imitations of Greek, later also of Roman coins. Soon, however, the Celts started to redesign the original motifs. The initial images were stylized and ornamentalized to such an extent, that the original coins are often hardly recognizable. 1 von 16 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. -

The Eleusinian Mysteries

© 2004 Frater E.V. - SRC&SSA Splendor Solis - No. II - 6 i & - 2004 A.D. The Eleusinian Mysteries his paper is no more than a write-up seriously interested to work out what the of notes I made for a group discussion Eleusinian myths and initiations are trying to Tof the Eleusinian Mysteries. Firstly I convey. give the myth around which the mysteries were based. I think I have told the basic story with From the foregoing it will be gleaned that the accuracy, but there are complications and final section is tentative and speculative in na- additions I have left out. These additions ture, and, as such, open to doubt and revision. make no material difference to the overall tale, and are actually bits and pieces of other myths The Myth tacked onto the main story at various times in history. One day Persephone (Proserpine, Cora, Kore) was gathering flowers with a group of The second section gives a brief outline of companions, and all was well until Persephone the basic format of the Lesser and Greater started to pick a lovely bunch of Narcissi. Mysteries. This is to provide a context for my Pluto (Hades), God of the Underworld, discussion of the more important matters, at noticed her, thought her very beautiful and, least as far as Golden Dawn initiates are with the permission of Zeus, abducted, raped concerned, which are the mystic initiations and carried Persephone away to his Under- themselves. Most of what is known of the world abode of gloom. Eleusinian Mysteries are the places and details of the exoteric celebrations; the more inte- Demeter (Ceres), the mother of Persephone, resting parts of the mysteries were jealously rushed to assist her daughter, but arrived too guarded secrets that were not to be revealed late, not even able to catch a glimpse of her to the outside World, and so little detail is seducer.