SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

The Seven Wonders of the World

Syrian Arab Republic Ministry of Education The National Center for the Distinguished The Seven Wonders of The World Preparation of : Rand Tamim Salman Under The Supervision of : Hiba Abboud 2015/2016 1 The Index : Page number The Index 2 The Index of The Pictures 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: The Wonders of The Ancient World. The Colossus of Rhodes 5 The Statue of Zeus at Olympia 6 The Temple of Artemis 8 The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus 12 The Great Pyramid of Giza 13 The Famed Lighthouse of Alexandria 16 The Hanging Gardens of Babylon 17 Chapter 2: The wonders of the modern world The wonders of the modern world 19 Conclusion 20 References 21 2 The Index of The Pictures: picture picture name Page number number 1 The Colossus of Rhodes 6 2 The Statue of Zeus 7 3 The Remains of Zeus Temple 8 4 Artemis 9 5 One of the column bases with carved 10 figures preserved at the British Museum. 6 The Temple of Artemis 11 7 The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus 13 8 The Great Pyramid of Giza 14 9 The Lighthouse of Alexandria 16 10 The hanging garden of Babylon 18 11 The wonders of the modern world 19 3 Introduction: When you hear the phrase "Seven Wonders of the World", people have different thoughts about what it means. In fact, if you survey people what are the seven wonders, you would probably get different answers. Depending on the era that you are talking about, you can get different results. From ancient time until this time, people have different points of view on what are those seven wonders. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

Journal I Bodrum Issue

ESCAPE JOURNEY INTO OUR CULTURE JOURNAL � I BODRUM ISSUE EDITOR'S NOTE 3 Dear friends, ’74Escape is a community platform that was born from a passion for exploring other people’s cultural experiences and making new discoveries through travel. Over time, the platform evolved into a wonderful collaborative and intimate space where we connect with friends from around the world, and share new finds and unforgettable memories. The emergence of a curated space and shop from this platform has always seemed like the next inevitable step. While the idea has long been on my mind, it was after enduring these last difficult months that the true philosophy and purpose began to take shape. Before we look outwards and explore, we must look within, and appreciate and celebrate our roots. Born from a heightened sense of unity and solidarity, this edition of the ’74Escape Store & Gallery hence intends to turn inwards, and shine a light on the creative and cultural production happening in Turkey today. This felt like an important time to activate our platform for the benefit of our community, and we have aimed to support our friends and their much loved brands, as well as newly discovered local designers, artisans and artists of Turkey. Istanbul is home to so many spirited brands that each share a unique vision and story that is rooted in our rich history, heritage and culture. The ’74Escape Store & Gallery at Maçakızı Bodrum this summer, celebrates and champions our homegrown talent, and offers a curated selection of exquisitely crafted contemporary works and products inspired by the Mediterranean way of life. -

Tales of Philip II Under the Roman Empire

Tales of Philip II under the Roman Empire: Aspects of Monarchy and Leadership in the Anecdotes, Apophthegmata , and Exempla of Philip II Michael Thomas James Welch BA (Hons. Class 1) M.Phil. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry P a g e 1 | 270 Abstract This thesis examines the role anecdotes, apophthegmata , and exempla play in the historiography of the Macedonian king Philip II in the Roman world - from the first century BCE to the fourth century CE. Most of the material examined comes from moral treatises, collections of tales and sayings, and military works by Greek and Latin authors such as Plutarch, Valerius Maximus, Aelian, Polyaenus, Frontinus, and Stobaeus (supplemented with pertinent material from other authors). This approach will show that while many of the tales surely originate from the earlier Greek world and Hellenistic times, the use and manipulation of the majority of them and the presentation of Philip are the product of a world living under Roman political and cultural domination. This thesis is divided into six chapters. Chapter one defines and discusses anecdotal material in the ancient world. Chapter two examines two emblematic ancient authors (Plutarch and Valerius Maximus) as case studies to demonstrate in detail the type of analysis required by all the authors of this study. Following this, the thesis then divides the material of our authors into four main areas of interest, particularly concerning Philip as a king and statesman. Therefore, chapter three examines Philip and justice. -

HELLENISTIC ART O. Palagia This Chapter Deals with Art In

CHAPTER 23 HELLENISTIC ART O. Palagia This chapter deals with art in Macedonia between the death of Alexander III (“the Great”) in 323 bc and the defeat of Perseus, last king of Macedon, at the battle of Pydna in 168 bc. As a result of Alexander’s conquest of the Persian Empire, a lot of wealth flowed into Macedonia.1 A large-scale con- struction programme was initiated soon after Alexander’s death, reinforc- ing city walls, rebuilding the royal palaces of Pella and Aegae (Vergina) and fijilling the countryside with monumental tombs. The archaeologi- cal record has in fact shown that a lot of construction took place during the rule of Cassander, who succeeded Alexander’s half-brother Philip III Arrhidaios to the throne of Macedon, and was responsible for twenty years of prosperity and stability from 316 to 297 bc. Excavations in Mace- donia have revealed very fijine wall-paintings, mosaics, and luxury items in ivory, gold, silver, and bronze reflecting the ostentatious elite lifestyle of a regime that was far removed from the practices of democratic city- states, Athens in particular.2 Whereas in Athens and the rest of Greece art and other treasures were reserved for the gods, in Macedonia they were primarily to be found in palaces, houses, and tombs. With the exception of the sanctuary of the Great Gods of Samothrace which was developed thanks to the generous patronage of Macedonian royalty from Philip II onwards, Macedonian sanctuaries lacked the monumental temples and cult statues by famous masters that were the glory of Athens, Delphi, Olympia, Argos, Epidauros, or Tegea, to name but a few. -

JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The Masters of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus Antonio Corso Kanellopoulos Foundation / Messenian Society, Psaromilingou 33, GR10553, Athens, Greece, phone +306939923573,[email protected] The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is one of the most renowned monuments of the ancient world.1 Mausolus must have decided to set up his monumental tomb in the centre of his newly built capital toward the end of his life: he died in 353 BC.2 After his death, some writers who were renowned in the oratory – Theopompus, Theodectes, Naucrates and less certainly Isocrates – went to the Hecatomnid court at Halicarnassus and took part in the competition held in the capital of Caria in order to deliver the most convincing oration on the death of Mausolus. The agon was won by Theopompus.3 Poets had also been invited on the same occasion.4 After the death of this satrap, the Mausoleum was continued by his wife and successor Artemisia (353-351 BC) and finished after her death,5 thus during the rule of Ada and Idrieus (351-344 BC). The shape of the building is known only generically thanks to the detailed description of the monument given by Pliny 36. 30-31 as well as to surviving elements of the tomb. The Mausoleum was composed of a rectangular podium containing the tomb of the satrap, above which there was a temple-like structure endowed with a peristasis, which was topped by a pyramidal roof, made of steps and supporting a marble quadriga. The architects who had been responsible of the Mausoleum were Satyrus and Pytheus, who also wrote a treatise ‘About the Mausoleum’ (Vitruvius 7, praef. -

Fourth Century Head in Central Museum, Athens Author(S): E

Fourth Century Head in Central Museum, Athens Author(s): E. F. Benson Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 15 (1895), pp. 194-201 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624069 . Accessed: 15/02/2015 15:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 15 Feb 2015 15:08:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 194 FOURTH CENTURY HEAD FOURTH CENTURY HEAD IN CENTRAL MUSEUM, ATHENS. G WAM 1w AW Mpg 04 My "WWI . ... ... ....... ... ........... 3q. 1 On 1S.- &ae ................. al xp i ME-. on" iU sm" to all. S I R , .................... ?a' ?g ....... .............. WES61 ER 01 AMR%%;Zug,LoaMmWWI THERE is among the fourth century works in the Central Museum at Athens a head found at Laurium. It is made of Parian marble but it has been completely discoloured by slag or refuse from the lead mines, and is now quite black. -

Greek Styles and Greek Art in Augustan Rome: Issues of the Present Versus

Originalveröffentlichung in: James I. Porter (Hrsg.), Classical Pasts. The Classical Traditions of Greece and Rome, Princeton; Oxford 2006, S. 237-269 Chapter 7 GREEK STYLES AND GREEK ART IN AUGUSTAN ROME: ISSUES OF THE PRESENT VERSUS RECORDS OF THE PAST Tonio Holscher Questions Roman art, as we have known since Winckelmann, was to a large extent shaped by “classical pasts,” by the inheritance of Greek art of various periods. In this, visual art corresponds to other domains of Roman culture, which in some respects can be described as a specific successor culture. Archaeological research has observed and evaluated this fact from controversial viewpoints.1 As long as the classical culture of Greece was valued as the highest measure of societal norms and artistic creation, no independent Roman strengths could be recognized in Roman art next to the Greek traditions; this was the basis for the sweeping negative judgment against “the art of the imitators.” Then, from around 1900, beginning with Franz Wickhoff and Alois Riegl,2 as the new archaeological arthistory developed a bold concept of cultural plurality and within this framework discovered and analyzed genuinely Roman forms and structures in visual art, the inherited Greek traditions were often judged to be a cultural burden and an interference in the development of an original Roman art. In neither case was the Greek inheritance seen as a productive element of Roman art. From the negative perspective, Roman art was of inferior impor tance because of its dependence on Greek models. On the positive side, it retained its originality and independence despite its occasional Greek overlay. -

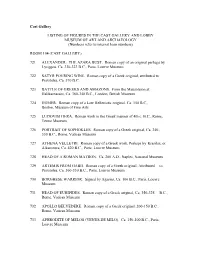

Complete Cast Gallery Listing

Cast Gallery LISTING OF FIGURES IN THE CAST GALLERY AND LOBBY MUSEUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY (Numbers refer to internal loan numbers) ROOM 104 (CAST GALLERY) 721 ALEXANDER: THE AZARA BUST. Roman copy of an original perhaps by Lysippos, Ca. 330-323 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 722 SATYR POURING WINE. Roman copy of a Greek original, attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 370 B.C. 723 BATTLE OF GREEKS AND AMAZONS. From the Mausoleion at Halikarnassos, Ca. 360-340 B.C., London, British Museum 724 HOMER. Roman copy of a Late Hellenistic original, Ca. 150 B.C., Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 725 LUDOVISI HERA. Roman work in the Greek manner of 4th c. B.C., Rome, Terme Museum 726 PORTRAIT OF SOPHOKLES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 340- 330 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 727 ATHENA VELLETRI. Roman copy of a Greek work, Perhaps by Kresilas, or Alkamenes, Ca. 420 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 728 HEAD OF A ROMAN MATRON. Ca. 200 A.D., Naples, National Museum 729 ARTEMIS FROM GABII. Roman copy of a Greek original, Attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 360-330 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 730 BORGHESE WARRIOR. Signed by Agasias, Ca. 100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 731 HEAD OF EURIPIDES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 350-325 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 732 APOLLO BELVEDERE. Roman copy of a Greek original, 200-150 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 733 APHRODITE OF MELOS (VENUS DE MILO). Ca. 150-100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 734 ZEUS BATTLING GIANTS. From the frieze of the Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon, Ca.