HELLENISTIC ART O. Palagia This Chapter Deals with Art In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Echo of Delphi: the Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A

An Echo of Delphi: The Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A. erhaps less well known than today’s to Northern India, and from Rus’ to Egypt, Olympics, the Pythian Games at was that of kaloi k’agathoi, the Beautiful and PDelphi, named after the slain Python the Good, certainly part of the tradition of Delphi and the Prophetesses, were a mani of Apollo. festation of the “the beautiful and the good,” a Essentially, since the Gods loved that hallmark of the Hellenistic spirituality which which was Good—and for the Athenians comes from the Mystery Schools. in particular, what was good was beautiful The Olympic Games, now held every —this maxim summed up Hellenic piety. It two years in alternating summer and winter was no great leap then to wish to present to versions, were the first and the best known the Gods every four years the best of what of the ancient Greek religious and cultural human beings could offer—in the arts, festivals known as the Pan-Hellenic Games. and in athletics. When these were coupled In all, there were four major celebrations, together with their religious rites, the three which followed one another in succession. lifted up the human body, soul, and spirit, That is the reason for the four year cycle of and through the microcosm of humanity, the Olympics, observed since the restoration the whole cosmos, to be Divinized. The of the Olympics in 1859. teachings of the Mystery Schools were played out on the fields and in the theaters of the games. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Oracle of Apollo Near Oroviai (Northern Evia Island, Greece) Viewed in Its Geοlogical and Geomorphological Context, Βull

Mariolakos, E., Nicolopoulos, E., Bantekas, I., Palyvos, N., 2010, Oracles on faults: a probable location of a “lost” oracle of Apollo near Oroviai (Northern Evia Island, Greece) viewed in its geοlogical and geomorphological context, Βull. Geol. Soc. of Greece, XLIII (2), 829-844. Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Proceedings of the 12th International Congress, Patras, May, 2010 ORACLES ON FAULTS: A PROBABLE LOCATION OF A “LOST” ORACLE OF APOLLO NEAR OROVIAI (NORTHERN EUBOEA ISLAND, GREECE) VIEWED IN ITS GEOLOGICAL AND GEOMORPHOLOGICAL CONTEXT I. Mariolakos1, V. Nikolopoulos2, I. Bantekas1, N. Palyvos3 1 University of Athens, Faculty of Geology, Dynamic, Tectonic and Applied Geology Department, Panepistimioupolis Zografou, 157 84, Athens, Greece, [email protected], [email protected] 2 Ministry of Culture, 2nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, L. Syggrou 98-100, 117 41 Athens, Greece, [email protected] 3 Harokopio university, Department of Geography, El. Venizelou 70 (part-time) / Freelance Geologist, Navarinou 21, 152 32 Halandri, Athens, Greece, [email protected] Abstract At a newly discovered archaeological site at Aghios Taxiarches in Northern Euboea, two vo- tive inscribed stelae were found in 2001 together with hellenistic pottery next to ancient wall ruins on a steep and high rocky slope. Based on the inscriptions and the geographical location of the site we propose the hypothesis that this is quite probably the spot where the oracle of “Apollo Seli- nountios” (mentioned by Strabo) would stand in antiquity. The wall ruins of the site are found on a very steep bedrock escarpment of an active fault zone, next to a hanging valley, a high waterfall and a cave. -

PL. LXI.J the Position of Polykleitos in the History of Greek

A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. 243 A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. [PL. LXI.J THE position of Polykleitos in the history of Greek sculpture is peculiarly tantalizing. We seem to know a good deal about his work. We know his statue of a Doryphoros from the marble copy of it in Naples, and we know his Diadumenos from two marble copies in the British Museum. Yet with these and other sources of knowledge, it happens that when we desire to get closer to his real style and to define it there occurs a void. So to speak, a bridge is wanting at the end of an otherwise agreeable journey, and we welcome the best help that comes to hand. There is, I think, some such help to be obtained from the terra-cotta statuette recently acquired in Smyrna by Mr. W. R. Paton. But first it may be of use to recall the reasons why the marble statues just mentioned must fail to convey a perfectly true notion of originals which we are justified in assuming were of bronze. In each of these statues the artist has been compelled by the nature of the material to introduce a massive support in the shape of a tree stem. That is at once a new element in the design, and, as a distinguished French sculptor1 has rightly observed, this new element called for a modification of the entire figure. This would have been true of a marble copy made even 1 M. Eugene Guillaume, in Eayet's dell' Tnst. Arch, 1878, p. 5. He gives Monuments de VArt Antique, pt. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

The Lighting of God's Face During Solar Stands in The

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 18, No 3, (2018), pp. 225-246 Copyright © 2018 MAA Open Access. Printed in Greece. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.2543786 THE LIGHTING OF GOD’S FACE DURING SOLAR STANDS IN THE APOLLO TEMPLE DELPHI Vlachos, A.1, Liritzis, I.1 and Georgopoulos, A.2 1University of the Aegean, Dept of Mediterranean Studies, Lab of Archaeometry, 1 Demokratias Str, Rhodes 85132, Greece 2National Technical University of Athens, School of Rural & Surveying Engineering, Dept of Topography, Iroon Polytechniou 915773 Zografos, Athens, Greece Received: 01/07/2018 Accepted: 25/11/2018 Corresponding author: I. Liritzis ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The direction of solar light and how it relates with the Apollo Temple in Delphi is investigated. Following up earlier investigation of defining the time to delivering an oracle and the historical reported position of a golden Apollo statue in the rear of the main structure (opisthodomos, adyton or Temple‘s sanctum) the sun lighting the statue‘s face during selected solar stands is virtually constructed. Based on both ancient and con- temporary sources, an accurately-oriented 3D model of the Temple was created, which incorporated win- dows in the sanctum area. A light and shadow study followed to establish the movement of shadows and presence of sunlight around and inside the Temple, during the important days for the ancient cult. It is shown that the shining of God‘s golden statue would have been possible, through windows, giving a dis- tinct impression of Apollo‘s presence in Delphi especially during his absence in the three winter months to the hyperborean lands between winter solstice and spring equinox. -

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

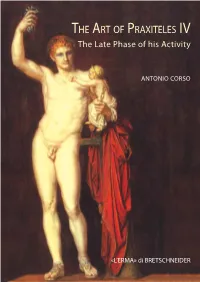

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

The Coins from the Necropolis "Metlata" Near the Village of Rupite

margarita ANDONOVA the coins from the necropolis "metlata" near the village of rupite... THE COINS FROM THE NECROPOLIS METLATA NEAR THE VILLAGE "OF RUPITE" (F. MULETAROVO), MUNICIPALITY OF PETRICH by Margarita ANDONOVA, Regional Museum of History– Blagoevgrad This article sets to describe and introduce known as Charon's fee was registered through the in scholarly debate the numismatic data findspots of the coins on the skeleton; specifically, generated during the 1985-1988 archaeological these coins were found near the head, the pelvis, excavations at one of the necropoleis situated in the left arm and the legs. In cremations in situ, the locality "Metlata" near the village of Rupite. coins were placed either inside the grave or in The necropolis belongs to the long-known urns made of stone or clay, as well as in bowls "urban settlement" situated on the southern placed next to them. It is noteworthy that out of slopes of Kozhuh hill, at the confluence of 167 graves, coins were registered only in 52, thus the Strumeshnitsa and Struma Rivers, and accounting for less than 50%. The absence of now identified with Heraclea Sintica. The coins in some graves can probably be attributed archaeological excavations were conducted by to the fact that "in Greek society, there was no Yulia Bozhinova from the Regional Museum of established dogma about the way in which the History, Blagoevgrad. souls of the dead travelled to the realm of Hades" The graves number 167 and are located (Зубарь 1982, 108). According to written sources, within an area of 750 m². Coins were found mainly Euripides, it is clear that the deceased in 52 graves, both Hellenistic and Roman, may be accompanied to the underworld not only and 10 coins originate from areas (squares) by Charon, but also by Hermes or Thanatos. -

Nicholas Victor Sekunda the SARISSA

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA ARCHAEOLOGICA 23, 2001 Nicholas Victor Sekunda THE SARISSA INTRODUCTION Recent years have seen renewed interest in Philip and Alexander, not least in the sphere of military affairs. The most complete discussion of the sarissa, or pike, the standard weapon of Macedonian footsoldiers from the reign of Philip onwards, is that of Lammert. Lammert collects the ancient literary evidence and there is little one can disagree with in his discussion of the nature and use of the sarissa. The ancient texts, however, concentrate on the most remarkable feature of the weapon - its great length. Unfor- tunately several details of the weapon remain unclear. More recent discussions o f the weapon have tried to resolve these problems, but I find myself unable to agree with many of the solutions proposed. The purpose of this article is to suggest some alternative possibilities using further ancient literary evidence and also comparisons with pikes used in other periods of history. 1 do not intend to cover those aspects of the sarissa already dealt with satisfactorily by Lammert and his predecessors'. THE PIKE-HEAD Although the length of the pike is the most striking feature of the weapon, it is not the sole distinguishing characteristic. What also distinguishes a pike from a common spear is the nature of the head. Most spears have a relatively broad head designed to open a wide flesh wound and to sever blood vessels. 1 hey are usually used to strike at the unprotected parts of an opponent’s body. The pike, on the other hand, is designed to penetrate body defences such as shields or armour. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level.