Tales of Philip II Under the Roman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginning Again: on Aristotle's Use of a Fable in the Meteorologica

Beginning Again: On Aristotle’s Use of a Fable in the Meteorologica Doron Narkiss Foremost of false philosophies, The sea harangues the daft, The possessed logicians of romance. — Laura Riding Book Two, Chapter Three of Aristotle’s Meteorologica opens as follows: The sea’s saltiness is our next subject. This we must discuss, and also the question whether the sea remains the same all the time, or whether there was a time when it did not exist, or will be a time when it will cease to exist and disappear as some people think. It is, then, generally agreed that the sea had a beginning if the universe as a whole had, for the two are supposed to have come into being at the same time. So, clearly, if the universe is eternal we must suppose that the sea is too. The belief held by Democritus that the sea is decreasing and that it will in the end disappear is like something out of Aesop’s fables [mythos]. For Aesop has a fable about Charybdis in which he says that she took one gulp of the sea and brought the mountains into view, and a second one and the islands appeared, and that her last one will dry the sea up altogether. Α fable like this was a suitable retort for Aesop to make when the ferryman annoyed him, but is hardly suitable for those who are seeking the truth [aletheia].' (Met. II.iii.356b) I want to focus on Aristotle’s apparently casual use of “Aesop” here — Ae sop as a representative of a certain way of knowing, and of the knowledge thus implied. -

AMBRACIA If You Are in Picturesque Arta, You Will Not Need to Travel to Visit Glorious Ambracia of Ancient Times

AMBRACIA If you are in picturesque Arta, you will not need to travel to visit glorious Ambracia of ancient times. It is at your feet. Of course modern buildings hide a large part of its magnificence. The rest is sufficient however, as it is just as attractive and significant. King Pyrrhus of Epirus should have loved Ambracia, maybe because it was the most important Corinthian colony after Kerkyra (Corfu). He held the Corinthians in great regard for their commercial prowess and the economic policy of expansion they practiced. In 625 BC Corinthian colonials had followed Gorgon, the illegitimate son of the tyrant of Corinth Kypselos, and settled on FOLLOW A ROUTE TO HISTORY the banks of the River Arachthos, where beautiful Arta lies today. Their settlement was part of an intelligent plan conceived by the Kypselides to build colonies and commercial and naval posts in appropriate positions, in order to dominate the West by monopolizing trade, the driving force of the economy. This is why we will find them in Lefkada, Corfu, Epidamnus etc. Gorgos and the Corinthian colonials pushed out of the region the Dryopes, but retained the name of the place which, according to mythology, is attributed to Ambracus, son of Thesprotos or to Ambracia, daughter of Melaneas, King HELLENIC REPUBLIC of the Dryopes. Ministry of Culture and Sports Ιoannina EPHORATE OF ANTIQUITIES OF ARTA Pedini Mary Beloyianni, Ιgoumenitsa Paramythia Plataria Phd. Archaeologist, Greek language teacher Responsible for educational programs of Diazoma Association language teacher Responsible for educational programs Greek Phd. Archaeologist, Sivota Perdika Margariti Parga Ammoudia Kanallaki Filipiada Louros Arta Nea Kerasounta Ambracia Kostakioi Dodona Gitana Archagelos Aneza Kanali Cassope Nicopolis Mitikas Preveza This small theatre, dating to the end of A few parts of this theatre have been the 4th – beginning of the 3rd century revealed (most of it is under adjacent buildings BC, is interesting because it was not built and the surface of the present road). -

Marginalia and Commentaries in the Papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes

Nikolaos Athanassiou Marginalia and Commentaries in the Papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes PhD thesis / Dept. of Greek and Latin University College London London 1999 C Name of candidate: Nikolaos Athanassiou Title of Thesis: Marginalia and commentaries in the papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes. The purpose of the thesis is to examine a selection of papyri from the large corpus of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes. The study of the texts has been divided into three major chapters where each one of the selected papyri is first reproduced and then discussed. The transcription follows the original publication whereas any possible textual improvement is included in the commentary. The commentary also contains a general description of the papyrus (date, layout and content) as well reference to special characteristics. The structure of the commentary is not identical for marginalia and hy-pomnemata: the former are examined in relation to their position round the main text and are treated both as individual notes and as a group conveying the annotator's aims. The latter are examined lemma by lemma with more emphasis upon their origins and later appearances in scholia and lexica. After the study of the papyri follows an essay which summarizes the results and tries to incorporate them into the wider context of the history of the text of each author and the scholarly attention that this received by the Alexandrian scholars or later grammarians. The main effort is to place each papyrus into one of the various stages that scholarly exegesis passed especially in late antiquity. Special treatment has been given to P.Wurzburg 1, the importance of which made it necessary that it occupies a chapter by itself. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote tables, maps, or illustrations Abdera 74 Cleomenes 237 ; coins 159, 276 , Abu Simbel 297 277, 279 ; food production 121, 268, Abydos 286 272 ; imports 268 ; Kleoitas 109 ; Achaea/Achaeans: Aigialos 213 ; Naucratis 269–271 ; pottery 191 ; basileus 128, 129, 134 ; Sparta 285 ; trade 268, 272 colonization 100, 104, 105, 107–108, Aegium 88, 91, 108 115, 121 ; democracy 204 ; Aelian 4, 186, 188 dialect 44 ; ethnos 91 ; Aeneas 109, 129 Herodotus 91 ; heroes 73, 108 ; Aeolians 45 , 96–97, 122, 292, 307 ; Homer 52, 172, 197, 215 ; dialect group 44, 45, 46 Ionians 50 ; migration 44, 45 , 50, Aeschines 86, 91, 313, 314–315 96 ; pottery 119 ; as province 68 ; Aeschylus: Persians 287, 308 ; Seven relocation 48 ; warrior tombs 49 Against Thebes 162 ; Suppliant Achilles 128, 129, 132, 137, 172, 181, Maidens 204 216 ; shield of 24, 73, 76, 138–139 Aetolia/Aetolians 20 ; dialect 299 ; Acrae 38 , 103, 110 Erxadieis 285 ; ethnos 91, 92 ; Acraephnium 279 poleis 93 ; pottery 50 ; West Acragas 38 , 47 ; democracy 204 ; Locris 20 foundation COPYRIGHTED 104, 197 ; Phalaris 144 ; Aëtos MATERIAL 62 Theron 149, 289 ; tyranny 150 Africanus, Sextus Julius 31 Adrastus 162 Agamemnon: Aeolians 97 ; anax 129 ; Aegimius 50, 51 Argos 182 ; armor 173 ; Aegina 3 ; Argos 3, 5 ; Athens 183, basileus 128, 129 ; scepter 133 ; 286, 287 ; captured 155 ; Schliemann 41 ; Thersites 206 A History of the Archaic Greek World: ca. 1200–479 BCE, Second Edition. Jonathan M. Hall. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, -

Pyla-Koutsopetria I Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town American Schools of Oriental Research Archeological Reports

PYLA-KOUTSOPETRIA I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF AN ANCIENT COASTAL TOWN AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH ARCHEOLOGICAL REPORTS Kevin M. McGeough, Editor Number 21 Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town PYLA-KOUTSOPETRIA I ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF AN ANCIENT COASTAL TOWN By William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew with contributions by Maria Andrioti, P. Nick Kardulias, Dimitri Nakassis, and Brandon R. Olson AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH • BOSTON, MA Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town by William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew Te American Schools of Oriental Research © 2014 ISBN 978-0-89757-069-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caraher, William R. (William Rodney), 1972- Pyla-Koutsopetria I : archaeological survey of an ancient coastal town / by William Caraher, R. Scott Moore, and David K. Pettegrew ; with contributions by Maria Andrioti, P. Nick Kardulias, Dimitri Nakassis, and Brandon Olson. pages cm. -- (Archaeological reports ; volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-89757-069-5 (alkaline paper) 1. Pyla-Kokkinokremos Site (Cyprus) 2. Archaeological surveying--Cyprus. 3. Excavations (Archaeology)--Cyprus. 4. Bronze age--Cyprus. 5. Cyprus--Antiquities. I. Moore, R. Scott (Robert Scott), 1965- II. Pettegrew, David K. III. Title. DS54.95.P94C37 2014 939’.37--dc23 2014034947 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. For Our Parents, Fred and Nancy Caraher Bob and Joyce Moore Hal and Sharon Pettegrew Introduction to A Provisional Linked Digital Version of Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town We are very pleased to release a digital version of Pyla-Koutsopetria I: Archaeological Survey of an Ancient Coastal Town (2014). -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

Download PDF Datastream

City of Praise: The Politics of Encomium in Classical Athens By Mitchell H. Parks B.A., Grinnell College, 2008 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Mitchell H. Parks This dissertation by Mitchell H. Parks is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Adele Scafuro, Adviser Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Johanna Hanink, Reader Date Joseph D. Reed, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Mitchell H. Parks was born on February 16, 1987, in Kearney, NE, and spent his childhood and adolescence in Selma, CA, Glenside, PA, and Kearney, MO (sic). In 2004 he began studying at Grinnell College in Grinnell, IA, and in 2007 he spent a semester in Greece through the College Year in Athens program. He received his B.A. in Classics with honors in 2008, at which time he was also inducted into Phi Beta Kappa and was awarded the Grinnell Classics Department’s Seneca Prize. During his graduate work at Brown University in Providence, RI, he delivered papers at the annual meetings of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South (2012) and the American Philological Association (2014), and in the summer of 2011 he taught ancient Greek for the Hellenic Education & Research Center program in Thouria, Greece, in addition to attending the British School at Athens epigraphy course. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

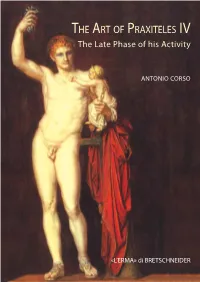

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Iamblichus and Julian''s ''Third Demiurge'': a Proposition

Iamblichus and Julian”s ”Third Demiurge”: A Proposition Adrien Lecerf To cite this version: Adrien Lecerf. Iamblichus and Julian”s ”Third Demiurge”: A Proposition . Eugene Afonasin; John M. Dillon; John F. Finamore. Iamblichus and the Foundations of Late Platonism, 13, BRILL, p. 177-201, 2012, Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts. Studies in Platonism, Neoplatonism, and the Platonic Tradition, 10.1163/9789004230118_012. hal-02931399 HAL Id: hal-02931399 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02931399 Submitted on 6 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Iamblichus and Julian‟s “Third Demiurge”: A Proposition Adrien Lecerf Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France [email protected] ABSTRACT. In the Emperor Julian's Oration To the Mother of the Gods, a philosophical interpretation of the myth of Cybele and Attis, reference is made to an enigmatic "third Demiurge". Contrary to a common opinion identifying him to the visible Helios (the Sun), or to tempting identifications to Amelius' and Theodorus of Asine's three Demiurges, I suggest that a better idea would be to compare Julian's text to Proclus' system of Demiurges (as exposed and explained in a Jan Opsomer article, "La démiurgie des jeunes dieux selon Proclus", Les Etudes Classiques, 71, 2003, pp. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

MAC II in General, All Greek Troops “Constitutionally

ALEXANDER’S FINAL ARMY An Honors Thesis for the Department of History By Jonathan A. Miller Thesis Advisor: Steven Hirsch Tufts University, 2011 AKNOWLEDGMENTS Alexander the Great is a man with whom many great leaders throughout history have been compared, a model of excellence whose achievements can never quite be matched. 2 My introduction to his legacy occurred in the third grade. Reading a biography of Julius Caesar for a class project, I happened across Plutarch’s famous description of Caesar’s reaction to reading a history of Alexander: “he was lost in thought for a long time, and then burst into tears. His friends were astonished, and asked the reason for his tears. ‘Do you not think,’ said he, ‘that it is a matter of sorrow that while Alexander, at my age, was already king of so many peoples, I have as yet achieved no brilliant success?’”1 This story captivated my imagination and stuck with me throughout my middle and high school years. Once at college, I decided to write a thesis on Alexander to better understand the one man capable of breeding thoughts of inadequacy in Caesar. This work is in many ways a tribute to both Caesar and Alexander. More pointedly, it is an exploration into the designs of a man at the feet of whom lay the whole world. This paper has meant a lot to me. I want to thank all those who made it possible. First and foremost, my undying gratitude goes to Professor Steven Hirsch, who has helped me navigate the difficult process of researching and writing this thesis.