JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Comparing and Contrasting the Athletic and Olympic Traditions of Then and Now

Steven Solomon and Mikkos Minos*: Comparing and contrasting the athletic and Olympic traditions of then and now By: Ashley Westhem Stanford, Calif.—Coming off of a thrilling experience in the 2012 London Olympics, Australian track star and Stanford University student, Steven Solomon sat down with me to talk about his Olympic Journey. Because he is so willing to impart his knowledge regarding the Olympics in Ancient Greece, Mikkos Minos of Athens (circa 350 BC) was asked to weigh in on his time as an Olympic athlete as well. Why do you put your body through so much stress in the name of competitive sport? SS: “The reason an athlete pushes himself through such painful barriers is because of the intrinsic values we get from victory. It’s that unknown factor of not knowing what you can accomplish. And that’s something that is true from the first Olympiad to the last Olympiad. I think success motivates people, once you taste a little bit of success you want to continue to strive for more success. You’re dying while you’re doing it, but whilst you’re dying now, you’re going to convert that into performance on the track, or in the gym.” MM: It is true that success is everything to us as a way to avoid shame and so we push ourselves to extreme limits. I compete for the honor of my family and also to warrant comparison to the gods. Also, competition is the only thing I’ve ever known and athletics has basically been my life since I was a boy. -

Teachers' Pay in Ancient Greece

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 5-1942 Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece Clarence A. Forbes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece * * * * * CLARENCE A. FORBES UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA STUDIES Ma y 1942 STUDIES IN THE HUMANITIES NO.2 Note to Cataloger UNDER a new plan the volume number as well as the copy number of the University of Nebraska Studies was discontinued and only the numbering of the subseries carried on, distinguished by the month and the year of pu blica tion. Thus the present paper continues the subseries "Studies in the Humanities" begun with "University of Nebraska Studies, Volume 41, Number 2, August 1941." The other subseries of the University of Nebraska Studies, "Studies in Science and Technology," and "Studies in Social Science," are continued according to the above plan. Publications in all three subseries will be supplied to recipients of the "University Studies" series. Corre spondence and orders should be addressed to the Uni versity Editor, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. University of Nebraska Studies May 1942 TEACHERS' PAY IN ANCIENT GREECE * * * CLARENCE A. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Download PDF Datastream

City of Praise: The Politics of Encomium in Classical Athens By Mitchell H. Parks B.A., Grinnell College, 2008 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Mitchell H. Parks This dissertation by Mitchell H. Parks is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Adele Scafuro, Adviser Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Johanna Hanink, Reader Date Joseph D. Reed, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Mitchell H. Parks was born on February 16, 1987, in Kearney, NE, and spent his childhood and adolescence in Selma, CA, Glenside, PA, and Kearney, MO (sic). In 2004 he began studying at Grinnell College in Grinnell, IA, and in 2007 he spent a semester in Greece through the College Year in Athens program. He received his B.A. in Classics with honors in 2008, at which time he was also inducted into Phi Beta Kappa and was awarded the Grinnell Classics Department’s Seneca Prize. During his graduate work at Brown University in Providence, RI, he delivered papers at the annual meetings of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South (2012) and the American Philological Association (2014), and in the summer of 2011 he taught ancient Greek for the Hellenic Education & Research Center program in Thouria, Greece, in addition to attending the British School at Athens epigraphy course. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

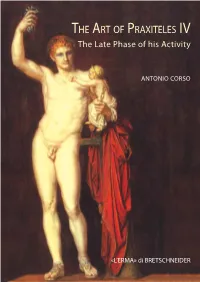

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

The Nature of Maussollos's Monarchy

The Nature of Maussollos’s Monarchy The Three Faces of a Dynastic Karian Satrap by Mischa Piekosz [email protected] Utrecht University RMA-THESIS Research Master Ancient Studies Supervisor: Rolf Strootman Second Reader: Saskia Stevens Student Number 3801128 Abstract This thesis analyses the nature of Maussollos’s monarchy by looking at his (self-)representation in epigraphy, architecture, coinage, and use of titulature vis-a-vis the concept of Hellenistic kingship. It shall be argued that he represented himself and was represented in three different ways – giving him three different ‘’faces’’. He represented himself as an exalted ruler concerning his private dedications and architecture, ever inching closer to deification, but not taking that final step. His deification was to be post mortem. Concerning diplomacy between him and the poleis, he adopted a realpolitik approach, allowing for much self-governance in return for accepting his authority. Maussollos strongly continued the dynastic image set up by his father Hekatomnos concerning the importance of Zeus Labraundos and his Sanctuary at Labraunda, turning the Sanctuary into the major Karian sanctuary. This dynastic parallel can also be seen concerning Hekatomnos’s and Maussollos’s burials, with both being buried as oikistes in terraced tombs, both the inner sanctums depicting Totenmahl-motifs and both being deified after death. Hekatomnos introduced coinage featuring Zeus Labraundos wielding a spear, representing spear- won land. Maussollos adopted this imagery and added Halikarnassian Apollo on the obverse depicting the locations of his two paradeisoi. As for titulature, the Hekatomnids in general eschewed using any which has led to confusion in the ancient sources, but the Hekatomnids were the satraps of Karia, ruling their native land on behalf of the Persian King.