The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Art 258: Ancient and Medieval Art Spring 2016 Sched#20203

Art 258: Ancient and Medieval Art Spring 2016 Sched#20203 Dr. Woods: Office: Art 559; e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Friday 8:00-8:50 am Course Time and Location: MWF 10:00 – 10:50 HH221 Course Overview Art 258 is an introduction to western art from the earliest cave paintings through the age of Gothic Cathedrals. Sculpture, painting, architecture and crafts will be analyzed from an interdisciplinary perspective, for what they reveal about the religion, mythology, history, politics and social context of the periods in which they were created. Student Learning Outcomes Students will learn to recognize and identify all monuments on the syllabus, and to contextualize and interpret art as the product of specific historical, political, social and economic circumstances. Students will understand the general characteristics of each historical or stylistic period, and the differences and similarities between cultures and periods. The paper assignment will develop students’ skills in visual analysis, critical thinking and written communication. This is an Explorations course in the Humanities and Fine Arts. Completing this course will help you to do the following in greater depth: 1) analyze written, visual, or performed texts in the humanities and fine arts with sensitivity to their diverse cultural contexts and historical moments; 2) describe various aesthetic and other value systems and the ways they are communicated across time and cultures; 3) identify issues in the humanities that have personal and global relevance; 4) demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of the humanities. Course Materials Text: F. -

'Stupid Midas'

‘Stupid Midas’ Visualising Musical Judgement and Tim Shephard Patrick McMahon Moral Judgement in Italy ca.1520 University of Sheffield 1. Musical Judgement and Moral Judgement 3. A) Cima da Conegliano, The Judgement Sat at the centre of the painting in contemporary elite of Midas, oil on panel, 1513-17. Statens The Ancient Discourse dress, Midas looks straight at the viewer, caught at the exact moment of formulating his faulty musical judgement. Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. Harmony is governed by proportion, and so is human tem- perament; thus music can affect human behavior ‘For rhythm and harmony penetrate deeply into the mind and take a most powerful hold on it, and, if education is good, bring an impart grace and beauty, if it is bad, the reverse’ (Plato, Republic) Music should therefore play a role in moral education Suggestive ‘music has indeed the power to induce a certain character of soul, and if it can do that, then An older, more position of clearly it must be applied to education’ (Aristotle, Politics) severe Tmolus, in Pan’s bow more modest makes a direct Good musical judgement engenders good moral judgement contemporary link between ‘the proper training we propose to give will make a man quick to perceive the shortcomings attire, also his musician- of works of art or nature …; anything beautiful he will welcome gladly … and so grow in true goodness of character; anything ugly he will rightly condemn and dislike’ (Plato, Republic) interrogates the ship and his viewer with his sexuality. The Renaissance Discourse gaze. -

Heracles and Philo of Alexandria: the Son of Zeus Between Torah and Philosophy, Empire and Stage

Chapter 8 Heracles and Philo of Alexandria: The Son of Zeus between Torah and Philosophy, Empire and Stage Courtney J. P. Friesen With few competitors, Heracles was one of the most popular and widely re- vered heroes of Greco-Roman antiquity. Though occupying a marginal place in the Homeric epics, he developed in complex directions within archaic Greek poetry, and in Classical Athens became a favorite protagonist among play- wrights, both of tragedy and comedy. From a famed monster-killer, to the trou- bled murderer of his own children, to the comic buffoon of prolific appetites, Heracles remained fixed in the imagination of ancient Greeks and Romans. Moreover, the son of Zeus was claimed as an ancestor for notable statesmen connected to both Alexandria and Rome (including Philip and Alexander of Macedon, the Ptolemies, and Mark Antony), and he was honored at cultic sites around the Mediterranean, including at the heart of the Roman Empire itself on the Ara Maxima. Jews living around the Greek and Roman world will inevitably have encoun- tered the mythologies and cults of Heracles in various forms. For instance, some Jewish writers, reflecting on this hero in light of their own traditions, made attempts to integrate him within the context of biblical genealogies.1 In addition, a natural correlation existed between Samson and Heracles, and al- ready in antiquity their extraordinary physical might was seen as comparable (Eusebius, PE 10.9.7; Augustine, Civ. 18.19).2 Recently, René Bloch has provided a useful survey of references to Heracles in the writings of Josephus in conjunc- tion with the Jewish historian’s wider engagement with Greek mythology.3 In 1 Cleomedus Malchus has Heracles marry the granddaughter of Abraham (Josephus, AJ 1.240–41); and according to unspecified sources, Heracles was the father of Melchizedek (Epiphanius, Pan. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Faculty Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Research and Scholarship 1974 A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S. Ridgway Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Ridgway, Brunilde S. 1974. A Story of Five Amazons. American Journal of Archaeology 78:1-17. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Story of Five Amazons* BRUNILDE SISMONDO RIDGWAY PLATES 1-4 THEANCIENT SOURCE dam a sua quisqueiudicassent. Haec est Polycliti, In a well-knownpassage of his book on bronze proximaab ea Phidiae, tertia Cresilae,quarta Cy- sculpturePliny tells us the story of a competition donis, quinta Phradmonis." among five artists for the statue of an Amazon This texthas been variously interpreted, emended, (Pliny NH 34.53): "Venereautem et in certamen and supplementedby trying to identifyeach statue laudatissimi,quamquam diversis aetatibusgeniti, mentionedby Pliny among the typesextant in our quoniamfecerunt Amazonas, quae cum in templo museums. It may thereforebe useful to review Dianae Ephesiaedicarentur, placuit eligi probatis- brieflythe basicpoints made by the passage,before simam ipsorum artificum, qui praesenteserant examining the sculpturalcandidates. iudicio,cum apparuitearn esse quam omnes secun- i) The Competition.The mention of a contest * The following works will be quoted in abbreviated form: von Bothmer D. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

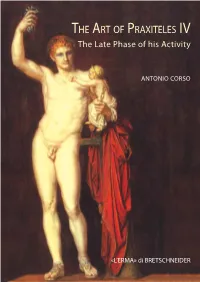

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Tῆς Πάσης Ναυτιλίης Φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea*

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 23 | 2010 Varia Tῆς πάσης ναυτιλίης φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea Denise Demetriou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/1567 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.1567 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2010 Number of pages: 67-89 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Denise Demetriou, « Tῆς πάσης ναυτιλίης φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea », Kernos [Online], 23 | 2010, Online since 10 October 2013, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ kernos/1567 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.1567 Kernos Kernos 23 (2010), p. .7-A9. T=> ?@AB> CDEFGHIB> JKHDL5 Aphrodite a d the Seau AbstractS This paper offers a co ection of genera y neg ected He enistic epigrams and some iterary and epigraphic e2idence that attest to the worship of Aphrodite as a patron deity of na2igation. The goddess8 temp es were often coasta not 1ecause they were p aces where _sacred prostitution” was practiced, 1ut rather 1ecause of Aphrodite8s association with the sea and her ro e as a patron of seafaring. The protection she offered was to anyone who sai ed, inc uding the na2y and traders, and is attested throughout the Mediterranean, from the Archaic to the He enistic periods. Further, the teLts eLamined here re2ea a metaphorica ink 1etween Aphrodite8s ro e as patron of na2igation and her ro e as a goddess of seLua ity. Résumé S Cet artic e pr sente une s rie d8 pigrammes he nistiques g n ra ement peu tudi es et que ques t moignages itt raires et pigraphiques attestant e cu te d8Aphrodite en tant que protectrice de a na2igation. -

E. General Subjects

Index E. General Subjects Academia (of Cicero) 13, 97 books-papyrus rolls-codices 22, 54–56, 65–71, 158–160 Adonis (image of) 48 booty, see plunder Aedes Concordiae, see Index B: Roma Boxers (sculptural group) 72 Akademia, see Index B: Athenai Bronze Age 21 Akropolis, see Index B: Athenai bronze from Korinthos 11, 12, 92 Alexandros the Great (dedications by) 28 bronze horses (statues of) 74 Alexandros the Great (portraits of) 47, 52, 94 bronze sculpture (large) 4, 14, 33, 43, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 72, 74, 82, 92, Alexandros the Great (spoliation by) 39, 41, 43, 47 122, 123, 130, 131–132, 134–135, 140, 144, 149, 151, 159, 160 Alexandros the Great’s table 2, 106 bronze sculpture (small) 14, 46, 53, 92, 106, 123, 138, 157 Alkaios (portrait of) 53 bronze tablets 81 altar 2, 42 Altar of Zeus, see Index B: Pergamon, Great Altar cameos 55–70 amazon 14, 134 Campus Martius, see Index B: Roma ancestralism 157, 159 canon 156, 159, 160–162 Antigonid Dynasty 46, 49 canopus 133 antiquarianism 4, 22, 25, 28, 31, 44, 55, 65–66, 73, 80, 81, 82, 156–157, Capitoline Hill, see Index B: Roma, Mons Capitolinus 159–160, 161 Capitolium, see Index B: Roma Anubis (statue of) 75 Carthaginians 9, 34, 104 Aphrodite, see Index C: Aphrodite catalogue, see also inventory, 93 Aphrodite (statue of) 52 censor, see Index D: censor Aphrodite of Knidos (statue of), see Index C: Praxiteles centaur, see Index D: kentauroi Apollon (statue of) 49, 72 Ceres (statue of) 72 Apollonios (portrait of) 53 chasing (chased silver) 104 Apoxyomenos (statue of), see Index C: Lysippos citronwood