THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Faculty Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Research and Scholarship 1974 A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S. Ridgway Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Ridgway, Brunilde S. 1974. A Story of Five Amazons. American Journal of Archaeology 78:1-17. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Story of Five Amazons* BRUNILDE SISMONDO RIDGWAY PLATES 1-4 THEANCIENT SOURCE dam a sua quisqueiudicassent. Haec est Polycliti, In a well-knownpassage of his book on bronze proximaab ea Phidiae, tertia Cresilae,quarta Cy- sculpturePliny tells us the story of a competition donis, quinta Phradmonis." among five artists for the statue of an Amazon This texthas been variously interpreted, emended, (Pliny NH 34.53): "Venereautem et in certamen and supplementedby trying to identifyeach statue laudatissimi,quamquam diversis aetatibusgeniti, mentionedby Pliny among the typesextant in our quoniamfecerunt Amazonas, quae cum in templo museums. It may thereforebe useful to review Dianae Ephesiaedicarentur, placuit eligi probatis- brieflythe basicpoints made by the passage,before simam ipsorum artificum, qui praesenteserant examining the sculpturalcandidates. iudicio,cum apparuitearn esse quam omnes secun- i) The Competition.The mention of a contest * The following works will be quoted in abbreviated form: von Bothmer D. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

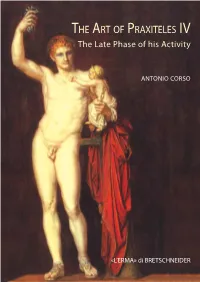

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

E. General Subjects

Index E. General Subjects Academia (of Cicero) 13, 97 books-papyrus rolls-codices 22, 54–56, 65–71, 158–160 Adonis (image of) 48 booty, see plunder Aedes Concordiae, see Index B: Roma Boxers (sculptural group) 72 Akademia, see Index B: Athenai Bronze Age 21 Akropolis, see Index B: Athenai bronze from Korinthos 11, 12, 92 Alexandros the Great (dedications by) 28 bronze horses (statues of) 74 Alexandros the Great (portraits of) 47, 52, 94 bronze sculpture (large) 4, 14, 33, 43, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 72, 74, 82, 92, Alexandros the Great (spoliation by) 39, 41, 43, 47 122, 123, 130, 131–132, 134–135, 140, 144, 149, 151, 159, 160 Alexandros the Great’s table 2, 106 bronze sculpture (small) 14, 46, 53, 92, 106, 123, 138, 157 Alkaios (portrait of) 53 bronze tablets 81 altar 2, 42 Altar of Zeus, see Index B: Pergamon, Great Altar cameos 55–70 amazon 14, 134 Campus Martius, see Index B: Roma ancestralism 157, 159 canon 156, 159, 160–162 Antigonid Dynasty 46, 49 canopus 133 antiquarianism 4, 22, 25, 28, 31, 44, 55, 65–66, 73, 80, 81, 82, 156–157, Capitoline Hill, see Index B: Roma, Mons Capitolinus 159–160, 161 Capitolium, see Index B: Roma Anubis (statue of) 75 Carthaginians 9, 34, 104 Aphrodite, see Index C: Aphrodite catalogue, see also inventory, 93 Aphrodite (statue of) 52 censor, see Index D: censor Aphrodite of Knidos (statue of), see Index C: Praxiteles centaur, see Index D: kentauroi Apollon (statue of) 49, 72 Ceres (statue of) 72 Apollonios (portrait of) 53 chasing (chased silver) 104 Apoxyomenos (statue of), see Index C: Lysippos citronwood -

Focus on Greek Sculpture

Focus on Greek Sculpture Notes for teachers Greek sculpture at the Ashmolean • The classical world was full of large high quality statues of bronze and marble that honoured gods, heroes, rulers, military leaders and ordinary people. The Ashmolean’s cast collection, one of the best- preserved collections of casts of Greek and Roman sculpture in the UK, contains some 900 plaster casts of statues, reliefs and architectural sculptures. It is particularly strong in classical sculpture but also includes important Hellenistic and Roman material. Cast collections provided exemplary models for students in art academies to learn to draw and were used for teaching classical archaeology. • Many of the historical casts, some dating back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, are in better condition than the acid rain-damaged originals from which they were moulded. They are exact plaster replicas made, with piece moulds that leave distinctive seams on the surface of the cast. • The thematic arrangement of the Cast Gallery presents the contexts in which statues were used in antiquity; sanctuaries, tombs and public spaces. Other galleries containing Greek sculpture, casts and ancient Greek objects Gallery 14: Cast Gallery Gallery 21: Greek and Roman Sculpture Gallery 16: The Greek World Gallery 7: Money Gallery 2: Crossing Cultures Gallery 14: Cast Gallery 1. Cast of early Greek kouros, Delphi, Greece, 2. Cast of ‘Peplos kore’, from Athenian Acropolis, c570BC c530BC The stocky, heavily muscled naked figure stands The young woman held an offering in her in the schematic ‘walking’ pose copied from outstretched left hand (missing) and wears an Egypt by early Greek sculptors, signifying motion unusual combination of clothes: a thin under- and life. -

Apoxyomenos: Discovery, Underwater Excavation, and Survey Jasen Mesić, MP, Parliament of Croatia, Committee for Science, Education, and Culture

Program as of September 29, 2015; subject to change Tuesday, October 13 --The Getty Center 9:45 a.m. Check-in opens Museum Lecture Hall lobby Viewing of Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World Exhibition Pavilion (opens 10:00 a.m.) Lunch on your own 12:30 p.m. Welcome and Introduction – Museum Lecture Hall Timothy Potts, J. Paul Getty Museum Kenneth Lapatin, J. Paul Getty Museum 1:00 p.m. Session I: Apoxyomenoi and Large-Scale Bronzes I – Museum Lecture Hall Chair: Jens Daehner, J. Paul Getty Museum The Bronze Athlete from Ephesos: Archaeological Background and History of its Classification Georg Plattner and Kurt Gschwantler, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna The Bronze Athlete from Ephesos: Restauration History and Stability Evaluation Bettina Vak, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Apoxyomenos: Discovery, Underwater Excavation, and Survey Jasen Mesić, MP, Parliament of Croatia, Committee for Science, Education, and Culture New Results on the Alloys of the Croatian Apoxyomenos Iskra Karniš Vidovi , Croatian Conservation Institute, Zagreb The Use of Inlays inč Early Greek Bronzes Seán Hemingway and Dorothy H. Abramitis, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Was the Colossus of Rhodes Cast in Courses or in Large Sections? Ursula Vedder, Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Munich Break; refreshments served © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust 19th International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, Oct. 13-17, 2015 Program as of September 29, 2015 Page 1 of 12 Program as of September 29, 2015; subject to change Tuesday, October 13 --The Getty Center (con’t) 3:30 p.m. Session II: Large-Scale Bronzes II – Museum Lecture Hall Chair: Sophie Descamps, Musée du Louvre, Paris A Royal Macedonian Portrait Head from the Sea off Kalymnos Olga Palagia, University of Athens The Bronze Head of Arsinoe III in Mantua and the Typology of Ptolemaic Divinization of the Archelaos Relief Patricia A. -

Kalokagathia: the Citizen Ideal in Classical Greek Sculpture

Kalokagathia: The Citizen Ideal in Classical Greek Sculpture York H. Gunther and Sumetanee Bagna- Dulyachinda Introduction Nothing useless can be truly beautiful. — William Morris Through the Archaic (c. 750-508BCE) and into the Classical period (c. 508-323BCE), the Ancient Greeks created sculptures of human beings that became increasingly realistic. 1 The height of this realism came with ‘Kritian Boy’ (480BCE) and the magnificent ‘Charioteer of Delphi’ (c. 470BCE), sculptures that represent human beings in lifelike detail, proportion and style. The representation of muscles, flesh, joints and bone and the use of contrapposto in ‘Kritian Boy’ presents us with a youth frozen in time yet alive; while the meticulous attention to the minutiae of the face and feet as well as the free flowing tunic of the ‘Charioteer of Delphi’ presents us with a competitor focused while in motion. But within a generation, realism was abandoned for an idealism. Sculptors suddenly (seemingly) set out to depict the details and proportions of the human body with mathematical precision and deliberate exaggeration. Polykleitos’ ‘Spear Bearer’ (c. 450BCE) and the recently discovered ‘Riace Bronzes’ (c. York H. Gunther is Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Program Director of the Humanities at Mahidol University International College, Thailand. Sumetanee ‘Marco’ Bagna-Dulyachinda is a recent graduate of Mahidol University International College, Thailand. 1 In identifying the end of the Archaic period and the beginning of the Classical period with the date 508BCE rather 480BCE as many historians do, we are emphasizing Cleisthenes’ democratic reforms (that followed Peististratus’ economic and social reforms), which emboldened the Athenians to, among other things, support the Ionian Greeks at the start of the Greco-Persian War. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

Finding the Originals: a Study of the Roman Copies of the Tyrannicides

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Finding the originals: a study of the Roman copies of the Tyrannicides and the Amazon group Courtney Ann Rader Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Rader, Courtney Ann, "Finding the originals: a study of the Roman copies of the Tyrannicides and the Amazon group" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 3630. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3630 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINDING THE ORIGINALS: A STUDY OF THE ROMAN COPIES OF THE TYRANNICIDES AND THE AMAZON GROUP A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Courtney Ann Rader B.A., Purdue University, 2008 May 2010 Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents for their love and constant support, and it was with their encouragement that I pursued this field. Thanks to my sister and brother for always listening. A special thanks goes to Dr. David Parrish for fueling my interest in Greek art and architecture. I would like to thank my committee members, Nick Camerlenghi and Steven Ross, for your thorough review and editing of my thesis. -

JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The Masters of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus Antonio Corso Kanellopoulos Foundation / Messenian Society, Psaromilingou 33, GR10553, Athens, Greece, phone +306939923573,[email protected] The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is one of the most renowned monuments of the ancient world.1 Mausolus must have decided to set up his monumental tomb in the centre of his newly built capital toward the end of his life: he died in 353 BC.2 After his death, some writers who were renowned in the oratory – Theopompus, Theodectes, Naucrates and less certainly Isocrates – went to the Hecatomnid court at Halicarnassus and took part in the competition held in the capital of Caria in order to deliver the most convincing oration on the death of Mausolus. The agon was won by Theopompus.3 Poets had also been invited on the same occasion.4 After the death of this satrap, the Mausoleum was continued by his wife and successor Artemisia (353-351 BC) and finished after her death,5 thus during the rule of Ada and Idrieus (351-344 BC). The shape of the building is known only generically thanks to the detailed description of the monument given by Pliny 36. 30-31 as well as to surviving elements of the tomb. The Mausoleum was composed of a rectangular podium containing the tomb of the satrap, above which there was a temple-like structure endowed with a peristasis, which was topped by a pyramidal roof, made of steps and supporting a marble quadriga. The architects who had been responsible of the Mausoleum were Satyrus and Pytheus, who also wrote a treatise ‘About the Mausoleum’ (Vitruvius 7, praef. -

Archaic and Classical Cult Statues in Greece

ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL CULT STATUES IN GREECE THE SETTING AND DISPLAY OF CULT IMAGES IN THE ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL PERIODS IN GREECE By SHERR! DAWSON, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts McMaster Uni versity © Copyright by Sherri Dawson, June 2002 MASTER OF ARTS (2002) McMaster University (Classical Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Setting and Display of Cult Images in the Archaic and Classical Peri ods in Greece. AUTHOR: Sherri Dawson, B. A. (Uni versity of Alberta) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Gretchen Umholtz NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 257. 11 ABSTRACT The focus of this thesis is on ancient archaic and classical Greek cult statues and how their placement reflects both the role of the statues themselves and the continuity in worship. Greek sanctuaries generally exhibited a strong continuity of cult in terms of building successive temples directly on top of the remains of their predecessors. The sanctuary of Hera on Samos and the sanctuary of Apollo at Didyma are two such sanctuaries in Asia Minor that exhibit this type of continuity even though their early temples were replaced by large superstructures. The temple of Athena Nike in Athens is another example of continuity, since the larger Classical temple was built on the same site as the archaic one. The Athenian Parthenon, the temple of Zeus at Olympia, the Classical Heraion at Argos and the Classical temple of Dionysos on the south slope in Athens, however, were not built on the same site as the archaic temples.