Another Note on the Sculpture of the Later Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Annual of the British School at Athens the Ionic Capital of The

The Annual of the British School at Athens http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH Additional services for The Annual of the British School at Athens: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Ionic Capital of the Gymnasium of Kynosarges Pieter Rodeck The Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 3 / November 1897, pp 89 - 105 DOI: 10.1017/S0068245400000770, Published online: 18 October 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068245400000770 How to cite this article: Pieter Rodeck (1897). The Ionic Capital of the Gymnasium of Kynosarges. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 3, pp 89-105 doi:10.1017/S0068245400000770 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH, IP address: 130.133.8.114 on 02 May 2015 COIN TYPE OF ELIS, RESTORED. THE IONIC CAPITAL OF THE GYMNASIUM OF KYNOSARGES. (PLATES VL—Vm.) THE excavations of the British School at Athens, in the winters of 1896 and 1897, had the result of determining that the site, on which they were carried on, had been a burial ground previous to the sixth cen- tury B.C. and again after the third century, and that, in the meantime, it must have been covered by the Greek building, of which we laid bare the foundations. The plan of this building resembles that of a large gymnasium; the period of its existence coincides with that during which we know the gymnasium of Kynosarges to have existed, and the position of the site is such as the various mentions of Kynosarges by classic authors leads us to expect. -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

Application of Color to Antique Grecian Architecture

# ''A \KlMinlf111? ^W\f ^ 4 ^ ih t ' - -- - A : ^L- r -Mi UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY .4k - ^» Class Book Volume MrlO-20M * 4 ^ if i : ' #- f | * f f f •is * id* ^ ; ' 4 4 - # T' t * * ; f + ' f 4 f- 4- f f -4 * 4 ^ I - - -HI- - * % . -4*- f 4- 4 4 # Hp- , * * 4 4- THE APPLICATION OF COLOR TO ANTIQUE GRECIAN ARCHITECTURE BY ARSELIA BESSIE MARTIN B. S. University of Illinois, 1909 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS fa 1910 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL June 4... 1910 190 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Viss .Arsel is Bessie ^srtin ENTITLED TM application of Color to antique Grecisn Architecture BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Architectural Decoration In Charge of Major Work Head of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination 170372 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 * UHJCi http:V7afchive.org/details/applicationofcol00mart THE APPLICATION OF COLOR TO ANTIQUE GRECIAN ARCHITECTURE CONTENTS Page | INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION I - A Kistorioal Review of the Controversy .... 4 SECTION II - A Review of the Earlier Styles IS A » Egyptian B. Assyrian C. Primitive Grecian SECTION III - Derivation of the Grecian Polychromy ..... 21 SECTION IV - General Considerations and Influences. ... 24 A. Climate B. Religion C. Natural Temperament of the Greeks D. Materials SECTION V - Coloring of Architectural Members 31 Proofs classified according to monuments SECTION VI - The Colors and Technique of Architectural Painting SECTION VII - Architectural Terra. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

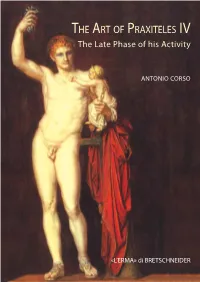

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

Aws Edition 1, 2009

Appendix B WS Edition 1, 2009 - [WI WebDoc [10/09]] A 6 Interior and Exterior Millwork © 2009, AWI, AWMAC, WI - Architectural Woodwork Standards - 1st Edition, October 1, 2009 B (Appendix B is not part of the AWS for compliance purposes) 481 Appendix B 6 - Interior and Exterior Millwork METHODS OF PRODUCTION Flat Surfaces: • Sawing - This produces relatively rough surfaces that are not utilized for architectural woodwork except where a “rough sawn” texture or nish is desired for design purposes. To achieve the smooth surfaces generally required, the rough sawn boards are further surfaced by the following methods: • Planing - Sawn lumber is passed through a planer or jointer, which has a revolving head with projecting knives, removing a thin layer of wood to produce a relatively smooth surface. • Abrasive Planing - Sawn lumber is passed through a powerful belt sander with tough, coarse belts, which remove the rough top surface. Moulded Surfaces: Sawn lumber is passed through a moulder or shaper that has knives ground to a pattern which produces the moulded pro[le desired. SMOOTHNESS OF FLAT AND MOULDED SURFACES Planers and Moulders: The smoothness of surfaces which have been machine planed or moulded is determined by the closeness of the knife cuts. The closer the cuts to each other (i.e., the more knife cuts per inch [KCPI]) the closer the ridges, and therefore the WS Edition 1, 2009 - [WI WebDoc [10/09]] smoother the resulting appearance. A Sanding and Abrasives: Surfaces can be further smoothed by sanding. Sandpapers come in grits from coarse to [ne and are assigned ascending grit numbers. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

The Sanctuary of Despotiko in the Cyclades. Excavations 2001–2012

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Yannos Kourayos – Kornelia Daifa – Aenne Ohnesorg – Katarina Papajanni The Sanctuary of Despotiko in the Cyclades. Excavations 2001–2012 aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue 2 • 2012 Seite / Page 93–174 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/123/4812 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2012-2-p93-174-v4812.0 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 Verlag / Publisher Hirmer Verlag GmbH, München ©2017 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

JIIA.Eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The Masters of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus Antonio Corso Kanellopoulos Foundation / Messenian Society, Psaromilingou 33, GR10553, Athens, Greece, phone +306939923573,[email protected] The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus is one of the most renowned monuments of the ancient world.1 Mausolus must have decided to set up his monumental tomb in the centre of his newly built capital toward the end of his life: he died in 353 BC.2 After his death, some writers who were renowned in the oratory – Theopompus, Theodectes, Naucrates and less certainly Isocrates – went to the Hecatomnid court at Halicarnassus and took part in the competition held in the capital of Caria in order to deliver the most convincing oration on the death of Mausolus. The agon was won by Theopompus.3 Poets had also been invited on the same occasion.4 After the death of this satrap, the Mausoleum was continued by his wife and successor Artemisia (353-351 BC) and finished after her death,5 thus during the rule of Ada and Idrieus (351-344 BC). The shape of the building is known only generically thanks to the detailed description of the monument given by Pliny 36. 30-31 as well as to surviving elements of the tomb. The Mausoleum was composed of a rectangular podium containing the tomb of the satrap, above which there was a temple-like structure endowed with a peristasis, which was topped by a pyramidal roof, made of steps and supporting a marble quadriga. The architects who had been responsible of the Mausoleum were Satyrus and Pytheus, who also wrote a treatise ‘About the Mausoleum’ (Vitruvius 7, praef. -

Fourth Century Head in Central Museum, Athens Author(S): E

Fourth Century Head in Central Museum, Athens Author(s): E. F. Benson Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 15 (1895), pp. 194-201 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624069 . Accessed: 15/02/2015 15:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 15 Feb 2015 15:08:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 194 FOURTH CENTURY HEAD FOURTH CENTURY HEAD IN CENTRAL MUSEUM, ATHENS. G WAM 1w AW Mpg 04 My "WWI . ... ... ....... ... ........... 3q. 1 On 1S.- &ae ................. al xp i ME-. on" iU sm" to all. S I R , .................... ?a' ?g ....... .............. WES61 ER 01 AMR%%;Zug,LoaMmWWI THERE is among the fourth century works in the Central Museum at Athens a head found at Laurium. It is made of Parian marble but it has been completely discoloured by slag or refuse from the lead mines, and is now quite black. -

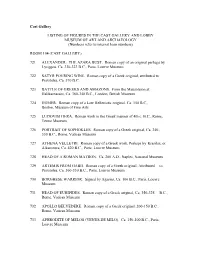

Complete Cast Gallery Listing

Cast Gallery LISTING OF FIGURES IN THE CAST GALLERY AND LOBBY MUSEUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY (Numbers refer to internal loan numbers) ROOM 104 (CAST GALLERY) 721 ALEXANDER: THE AZARA BUST. Roman copy of an original perhaps by Lysippos, Ca. 330-323 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 722 SATYR POURING WINE. Roman copy of a Greek original, attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 370 B.C. 723 BATTLE OF GREEKS AND AMAZONS. From the Mausoleion at Halikarnassos, Ca. 360-340 B.C., London, British Museum 724 HOMER. Roman copy of a Late Hellenistic original, Ca. 150 B.C., Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 725 LUDOVISI HERA. Roman work in the Greek manner of 4th c. B.C., Rome, Terme Museum 726 PORTRAIT OF SOPHOKLES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 340- 330 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 727 ATHENA VELLETRI. Roman copy of a Greek work, Perhaps by Kresilas, or Alkamenes, Ca. 420 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 728 HEAD OF A ROMAN MATRON. Ca. 200 A.D., Naples, National Museum 729 ARTEMIS FROM GABII. Roman copy of a Greek original, Attributed to Praxiteles, Ca. 360-330 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 730 BORGHESE WARRIOR. Signed by Agasias, Ca. 100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 731 HEAD OF EURIPIDES. Roman copy of a Greek original, Ca. 350-325 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 732 APOLLO BELVEDERE. Roman copy of a Greek original, 200-150 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museum 733 APHRODITE OF MELOS (VENUS DE MILO). Ca. 150-100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum 734 ZEUS BATTLING GIANTS. From the frieze of the Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon, Ca.