And Others Entitled "The Vocal Behavior of Infants"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Circular Conference Colombia in the IYL 2015

SECOND ANNOUNCEMENT International Conference \Colombia in the International Year of Light" June 16 - 19, 2015 Bogot´a& Medell´ın,Colombia 1 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Dear Colleagues, The International Conference Colombia in the International Year of Light (IYL- ColConf2015) will be held in Bogot´a,Colombia on 16-17 June 2015, and Medell´ın, Colombia on 18-19 June 2015. IYLColConf2015 is expected to bring together 500- 600 scientists, other professionals, and students engaged to research, development and applications of science and technology of light. You are invited to attend this conference and take part in the discussions about the \state of the art" in this field, in company of world-renowned scientists. Organizers and promoters of this conference include: The Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes), Bogot´a;the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (National University of Colombia), Bogot´aand Medell´ın; the Universidad de Antioquia (University of Antioquia), Medell´ın; the Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales (Colombian Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences); Colombian research groups working on topics related to optical sciences, and academic programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We are honored to host IYLColConf2015 in Bogot´aand Medell´ın,two of the main cities of Colombia, in June 2015. We look forward to seeing you there. Sincerelly yours, On behalf of the Executive Committee, Prof. Jorge Mahecha. Institute of Physics, Universidad de Antioquia. page 2 of 27 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Contents • IYLColConf2015 Committees 3 • General Information and Deadlines 5 • Registration and Support Policy 7 • Further Information 8 • Scientific Program 9 • Conference proceedings 25 • Travel and Transportation 25 • Hotels and Accommodations 25 • Miscellaneous 25 • Sponsors 27 IYLColConf2015 Committees International Advisory Committee Prof. -

Austria University of Vienna All Belgium Catholic University Of

Monash University - Exchange Partners Faculties Minimum GPA/WAM Austria University of Vienna All WAM 65 Belgium Catholic University of Leuven BusEco WAM 70 Brazil Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) of Rio de Janeiro All WAM 70 Brazil Universidade de Brasilia All WAM 70 Brazil State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) Brazil All WAM 70 Brazil University of Sao Paulo Arts WAM 70 Canada Bishop's University All WAM 70 Canada Carleton University All WAM 70 Canada HEC Montreal BusEco GPA 3.0 Canada Queen's University Arts, Science, Engineering, BusEco GPA 2.7 Canada Simon Fraser University All WAM 70 Canada University of British Columbia All except BusEco & Law WAM 85 Canada University of Ottawa BusEco WAM 70 Canada University of Waterloo All WAM 70 Canada York University All except BusEco & Law WAM 70 Canada Osgoode Hall Law School (York University) Law WAM 70 - previous 2 yrs Chile La Pontificia Universidad Catholic de Chile All WAM 70 Chile Universidad Diego Portales All WAM 70 Chile Universidad de Chile All WAM 70 China Peking University All WAM 60 China Shanghai Jiao Tong University All WAM 60 China Sichuan University All WAM 60 China Tsinghua University All WAM 60 China Nanjing University All WAM 60 China Fudan University All WAM 60 China Harbin Institute of Technology All WAM 60 China Sun Yat-Sen University All WAM 60 China Univeristy of Science and Technology of China All WAM 60 China Xi'an Jiaotong University All WAM 60 China Zhejinag University All WAM 60 Colombia University of Antioquia All WAM 70 Denmark Copenhagen Business School -

Welcoming a New Century • Focus on Hope • Seminarian Ministries

The Crossroads The Alumni Magazine for Theological College • Fall 2018 Welcoming a New Century • Focus on Hope • Seminarian Ministries Theological College | The National Seminary of The Catholic University of America A Letter from the Rector The Crossroads is published three times a year by the Office of Institutional Advance- ment of Theological College. It is distributed via non-profit mail to alumni, bishops, voca- S. SVL II PI tion directors, and friends of TC. R T A II N I W Rector M A E S Rev. Gerald D. McBrearity, P.S.S. (’73) S H I N M G Media & Promotions V L T L O I N Managing Editor G I S Suzanne Tanzi ✣ A Horizon of Hope Contributing Writers Jonathan Barahona • James Buttner Roger Schutz in his In order to prepare future priests who will be able to restore hope Liam Gallagher • Dr. Kathleen Galleher book, Living Today for and confidence amongst the people of God, Theological College is Rev. Matthew Gworek • Cornelia Hart Contents responsible for discerning the readiness of a priesthood candidate Alexandre Jiménez-Alcântara God, wrote, “During to enter the seminary and benefit from the formation program; Michael Kielor • Rev. Mark Morozowich the darkest periods of psychological tests and interviews, background checks, training Dr. John McCarthy • Justin Motes A Letter from the Rector ................................................................... 1 history, quite often a programs related to protecting the most vulnerable are all essential Mary Nauman • Jonathan Pham to the process of acceptance into Theological College. Once accept- Community News small number of men Michael Russo • Charles Silvas and women, scattered ed, every seminarian is accompanied by a spiritual director and a Cassidy Stinson Ordinations 2018 ........................................................................ -

Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration

Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final report Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final report © The Research Council of Norway 2014 The Research Council of Norway P.O.Box 2700 St. Hanshaugen N–0131 OSLO Telephone: +47 22 03 70 00 Telefax: +47 22 03 70 01 [email protected] www.rcn.no/english The report can be ordered at: www.forskningsradet.no/publikasjoner or green number telefax: +47 800 83 001 Design cover: Design et cetera AS Printing: 07 Gruppen/The Research Council of Norway Number of copies: 150 Oslo, March 2014 ISBN 978-82-12-03310-8 (print) ISBN 978-82-12-03311-5 (pdf) Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway’s Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final Report March 14, 2014 Authors Alexandre Beaudet David Campbell Grégoire Côté Stefanie Haustein Christian Lefebvre Guillaume Roberge Other contributors Philippe Deschamps Leroy Fife Isabelle Labrosse Rémi Lavoie Aurore Nicol Bastien St-Louis Lalonde Matthieu Voorons Contact information Grégoire Côté, Vice-President, Bibliometrics [email protected] Brussels | Montreal | Washington Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway’s Strategy for Final Report International Research Collaboration Contents Contents .................................................................................................................. i Tables ................................................................................................................... iii -

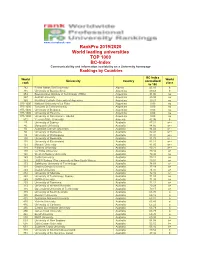

Rankpro 2019/2020 World Leading Universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and Information Availability on a University Homepage Rankings by Countries

www.cicerobook.com RankPro 2019/2020 World leading universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and information availability on a University homepage Rankings by Countries BC-Index World World University Country normalized rank class to 100 782 Ferhat Abbas Sétif University Algeria 45.16 b 715 University of Buenos Aires Argentina 49.68 b 953 Buenos Aires Institute of Technology (ITBA) Argentina 31.00 no 957 Austral University Argentina 29.38 no 969 Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina Argentina 20.21 no 975-1000 National University of La Plata Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 Torcuato Di Tella University Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Belgrano Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Palermo Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of San Andrés - UdeSA Argentina 0.00 no 812 Yerevan State University Armenia 42.96 b 27 University of Sydney Australia 87.31 a++ 46 Macquarie University Australia 84.66 a++ 56 Australian Catholic University Australia 84.02 a++ 80 University of Melbourne Australia 82.41 a++ 93 University of Wollongong Australia 81.97 a++ 100 University of Newcastle Australia 81.78 a++ 118 University of Queensland Australia 81.11 a++ 121 Monash University Australia 81.05 a++ 128 Flinders University Australia 80.21 a++ 140 La Trobe University Australia 79.42 a+ 140 Western Sydney University Australia 79.42 a+ 149 Curtin University Australia 79.11 a+ 149 UNSW Sydney (The University of New South Wales) Australia 79.01 a+ 173 Swinburne University of Technology Australia 78.03 a+ 191 Charles Darwin University Australia 77.19 -

Wake Forest College Faculty 1

Wake Forest College Faculty 1 Professor of Theatre WAKE FOREST COLLEGE BA, UNC-Chapel Hill; MFA, UNC-Greensboro. FACULTY Elizabeth Mazza Anthony (1998) Associate Teaching Professor of French Studies Date following name indicates year of appointment. Listings represent those BA, Duke University; MA, PhD, UNC-Chapel Hill. faculty teaching either full or part-time during the fall 2020 and/or spring Diana R. Arnett (2014) 2021. Associate Teaching Professor of Biology Irma V. Alarcón (2005) BS, MA, Youngstown State University; PhD, Kent State University. Associate Professor of Spanish and Italian Lisa Ashe (2016) BA, Universidad de Concepción (Chile); MA, PhD , Indiana University. Part-time Assistant Professor of Art Jane W. Albrecht (1987) BS, University of Tennessee; MA, PhD, University of Virginia. Professor of Spanish and Italian Miriam A. Ashley-Ross (1997) BA, Wright State University; MA, PhD , Indiana University. Professor of Biology Guillermo Alesandroni (2020) BS, Northern Arizona University; PhD, University of California (Irvine). Visiting Assistant Professor Robert J. Atchison (2010) BS, National University of Rosario; MS, University of Illinois at Chicago; Associate Professor of Communication and Director of Debate PhD, Oklahoma State University. BA, MA, Wake Forest University; PhD, University of Georgia. Rebecca W. Alexander (2000) Alison Atkins (2013) F.M. Kirby Family Faculty Fellow and Professor of Chemistry Assistant Teaching Professor of Spanish and Italian BS, Delaware; PhD, University of Pennsylvania. BA, Wake Forest University; MA, PhD , University of Virginia. Lucy Alfrd (2020) Emily A. Austin (2009) Assistant Professor of English Assistant Professor of Philosophy BA, University of Virginia; Phd, Stanford University; PhD, University of BA, Hendrix College; PhD, Washington University (St. -

Javier Mejia Phone: +971 2628 66 92 | E-Mail: [email protected] | Web: Javiermejia.Strikingly.Com

Javier Mejia Phone: +971 2628 66 92 j E-mail: [email protected] j Web: javiermejia.strikingly.com Current employment Stanford University Palo Alto, US Postdoctoral Research Fellow 2021 { Present Education Los Andes University Bogota, Colombia Ph.D. in Economics (with honors) 2013 { 2018 Stanford University Palo Alto, US Visiting Student Researcher 2016 { 2017 Los Andes University Bogota, Colombia M.A. in Economics 2013 { 2015 University of Antioquia Medellin, Colombia B.A. in Economics 2007 { 2012 Research Experience Stanford University Palo Alto, US Postdoctoral Research Fellow 2021 { Present New York University Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi, UAE Postdoctoral Associate 2018 { 2021 University of Bordeaux Bordeaux, France Visiting Research Fellow 2017 Los Andes University Bogota, Colombia Research Assistant 2013-2016 Teaching Experience Stanford University j Undergraduate level 2021-Present • Lecturer. Courses: Wealth of Nations, Societal Collapse New York University Abu Dhabi j Undergraduate level 2020-2021 • Lecturer. Courses: Wealth of Nations Los Andes University j Graduate and undergraduate level 2014-2016 • Adjunct professor. Courses: Principles of Mathematics • Teaching assistant. Courses: Advanced Macroeconomics, Economic History of Colombia Cooperative University of Colombia j Undergraduate level 2012-2013 • Adjunct professor. Courses: Economic Theory University Foundation of the Andean Region j Undergraduate level 2012-2013 • Adjunct professor. Courses: Economic Theory, Economic Policy Outreach Activity Forbes -Latin America- 2020 { -

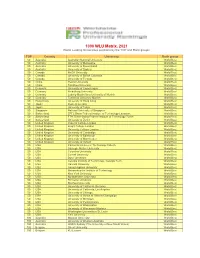

WLU Table 2021

1000 WLU Matrix. 2021 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Queensland World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Denmark University of Copenhagen World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Singapore National University of Singapore World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 Switzerland University of Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie -

Colombia – Student Activists – ESMAD – Universities

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: COL33017 Country: Colombia Date: 16 April 2008 Keywords: Colombia – student activists – ESMAD – Universities This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide a description of an attack on protesters by the authorities (Anti- disturbance Mobile Squadrons or ESMAD) on 22 September 2005 at Valley University (Universidad del Valle – CERUV), including a list of the names of killed or wounded. Please include any eyewitness type reports with specific details. 2. Please provide information about ensuing, related protests, including about a protest at La Ermita church. 3. Please advise as to whether there was a national strike in Bogota on 22 May 2007? What was its purpose? 4. Please advise whether student activists were targeted in 2006 or 2007 by paramilitaries or the authorities? For what reasons were they targeted? Is there evidence they were seriously harmed? RESPONSE 1. Please provide a description of an attack on protesters by the authorities (Anti-disturbance Mobile Squadrons or ESMAD) on 22 September 2005 at Valley University (Universidad del Valle – CERUV), including a list of the names of killed or wounded. -

Wake Forest College Faculty 1

Wake Forest College Faculty 1 T. Michael Anderson (2010) WAKE FOREST COLLEGE Associate Professor of Biology FACULTY BS, Oregon State University; PhD, Syracuse University. Sharon G. Andrews (1994) Date following name indicates year of appointment. Listings represent those Professor of Theatre faculty teaching either full or part-time during the fall 2020 and/or spring BA, UNC-Chapel Hill; MFA, UNC-Greensboro. 2021. Kendra Andrews (2021) Irma V. Alarcón (2005) Assistant Teaching Professor of English Associate Professor of Spanish and Italian BA, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; MA, University of North BA, Universidad de Concepción (Chile); MA, PhD , Indiana University. Carolina at Charlotte; PhD, North Carolina State University. Jane W. Albrecht (1987) Elizabeth Mazza Anthony (1998) Professor of Spanish and Italian Teaching Professor of French Studies BA, Wright State University; MA, PhD , Indiana University. BA, Duke University; MA, PhD, UNC-Chapel Hill. Guillermo Alesandroni (2020) Diana R. Arnett (2014) Visiting Assistant Professor Associate Teaching Professor of Biology BS, National University of Rosario; MS, University of Illinois at Chicago; BS, MA, Youngstown State University; PhD, Kent State University. PhD, Oklahoma State University. Miriam A. Ashley-Ross (1997) Rebecca W. Alexander (2000) Professor of Biology F.M. Kirby Family Faculty Fellow and Professor of Chemistry BS, Northern Arizona University; PhD, University of California (Irvine). BS, Delaware; PhD, University of Pennsylvania. Robert J. Atchison (2010) Lucy Alford (2020) Associate Professor of Communication and Director of Debate Assistant Professor of English BA, MA, Wake Forest University; PhD, University of Georgia. BA, University of Virginia; Phd, Stanford University; PhD, University of Alison Atkins (2013) Aberdeen. -

Ccl Frankfurt Englis

CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 2 The International Book Fair of Bogotá (FILBo for its acronym in Spanish) turns 31 in its next edition, which will take place from April 17th to May 2th, 2018. We want to celebrate not only the impressive growth of its academic program in recent years, which has had the participation of authors of extraordinary international relevance such as Literature Nobel prize recipients Svetlana Alexievich, Mario Vargas Llosa, and J.G.M. Le Clezio, but also the development of its international relevance such as Literature and, especially, our new Hall of Rights, a meeting place for agents, editors, and scouts interested in the Spanish-speaking publishing market. This catalog is a window to contemporary Colombian publishing. Throughout its pages you will find a series of recently published books of fiction, nonfiction, and children’s literature, all of which have their rights available for sale. The books shown in this catalog have been hand picked by Colombian publishers, with the aim of showcasing the best of their production. We are sure that here you will find something interesting as well in here you will find something that suits your interests. At the International Frankfurt Book Fair we not only celebrate the creation of the FILBo Hall of Rights as a new standard for the exchanging of rights during the first semester of the year in Latin America; we also want to showcase Bogotá as a literary and tourist destination: a city of books. CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 3 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 4 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 5 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 6 University of La Sabana We are a publishing house whose sole purpose has been to publish the intellectual production of our teachers through different types formats such as books, magazines, brochures and manuals, as the result of their research made in the University, as well as any other other kind of texts or documents that could be of interest for our own community. -

RF Annual Report

The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, 1960 FnilWDAT JAN 2 Q 2001 LIBRARY > iii West 5oth Street, New York 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation \%0 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation CONTENTS TRUSTEES, OFFICERS, AND COMMITTEES, 1960-1961 xvi TRUSTEES, OFFICERS, AND COMMITTEES, 1961-1962 xviii OFFICERS AND STAFF MEMBERS, 1960 xx LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL xxvii The President's Review John D. Rockefeller, Jr., 1874-1960 3 Financial Summary for 1960 7 Program Dynamics 8 The Local Relevance of Learning 12 The Agricultural Development of Africa 20 Training in International Affairs 26 Language: Barrier or Bridge? 34 Communication in the Americas 36 An International Study Center for Modern Art 38 The Art of the American Indian 39 A Registry for American Craftsmen 4] The International Rice Research Institute 43 The Foundation's Operating Programs Agriculture 45 Arthropod-Borne Viruses 63 Organizational Information • 74 Summary of Appropriations Account and Principal Fund 81 ILLUSTRATIONS following 82 v 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation Medical and Natural Sciences INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT 87 PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION Harvard Medical Center: Central Medical Library 90 All-India Institute of Medical Sciences: Teaching Hospital and Scholarship Program 91 University College of the West Indies: Faculty of Medicine 92 University of Guadalajara: Faculty of Medicine 93 American University of Beirut: Medical School 94 National Institute of Nutrition, Mexico: Hospital for Nutritional Diseases 95 University of Ankara: Research Institute