Paramilitarism in a Post-Demobilization Context? Insights from the Department of Antioquia in Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Servicio De Vigilancia Y Pronóstico De La Amenaza Por Deslizamientos

SERVICIO DE SEGUIMIENTO Y PRONÓSTICO DE LA AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS Boletín No. 328 . Bogotá D.C., Jueves 18 de diciembre de 2014, 11:00 am. AMENAZA ALTA. PARA TOMAR ACCIÓN AMENAZA MODERADA PARA PREPARARSE AMENAZA BAJA PARA INFORMARSE RESUMEN Debido a las condiciones de humedad y a las precipitaciones de los últimos días en el país, se presenta probabilidad de amenaza por deslizamientos de tierra detonados por lluvia en los departamentos de Boyacá, Caldas, Caquetá, Casanare, Cauca, Cesar, Chocó, Cundinamarca, Huila, Meta, Nariño, Norte de Santander, Putumayo, Quindío, Santander, Tolima y Valle del Cauca. Mapa 1. Pronóstico nacional de amenaza por deslizamientos de tierra detonados por lluvias. 1 Subdirección de Ecosistemas e Información Ambiental Grupo de Suelos y Tierras SERVICIO DE SEGUIMIENTO Y PRONÓSTICO DE LA AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS REGIÓN CARIBE Probabilidad baja de ocurrencia de deslizamientos de tierra ocasionados por lluvias principalmente en los departamentos de Cesar, Córdoba y Magdalena. AMENAZA BAJA Cesar: se pronostica amenaza baja por deslizamientos de tierra en áreas inestables en jurisdicción de los municipios de La Gloria, Pailitas y Pelaya. Córdoba: se pronostica amenaza baja por deslizamientos de tierra en áreas inestables en jurisdicción de los municipios de Montelíbano y Puerto Libertador. Magdalena: se pronostica amenaza baja por deslizamientos de tierra en áreas inestables en jurisdicción del municipio de Ciénaga. REGIÓN ANDINA Probabilidad moderada y baja de ocurrencia de deslizamientos de tierra ocasionados por lluvias principalmente en los departamentos de Antioquia, Boyacá, Caldas, Cauca, Cundinamarca, Huila, Norte de Santander y Santander. Mapa 2. Pronóstico de la amenaza por deslizamientos de tierra detonados por lluvias en los departamentos de Antioquia, Caldas y Cundinamarca. -

UNHCR Colombia Receives the Support of Private Donors And

NOVEMBER 2020 COLOMBIA FACTSHEET For more than two decades, UNHCR has worked closely with national and local authorities and civil society in Colombia to mobilize protection and advance solutions for people who have been forcibly displaced. UNHCR’s initial focus on internal displacement has expanded in the last few years to include Venezuelans and Colombians coming from Venezuela. Within an interagency platform, UNHCR supports efforts by the Government of Colombia to manage large-scale mixed movements with a protection orientation in the current COVID-19 pandemic and is equally active in preventing statelessness. In Maicao, La Guajira department, UNHCR provides shelter to Venezuela refugees and migrants at the Integrated Assistance Centre ©UNHCR/N. Rosso. CONTEXT A peace agreement was signed by the Government of Colombia and the FARC-EP in 2016, signaling a potential end to Colombia’s 50-year armed conflict. Armed groups nevertheless remain active in parts of the country, committing violence and human rights violations. Communities are uprooted and, in the other extreme, confined or forced to comply with mobility restrictions. The National Registry of Victims (RUV in Spanish) registered 54,867 displacements in the first eleven months of 2020. Meanwhile, confinements in the departments of Norte de Santander, Chocó, Nariño, Arauca, Antioquia, Cauca and Valle del Cauca affected 61,450 people in 2020, as per UNHCR reports. The main protection risks generated by the persistent presence of armed groups and illicit economies include forced recruitment of children by armed groups and gender- based violence – the latter affecting in particular girls, women and LGBTI persons. Some 2,532 cases of GBV against Venezuelan women and girls were registered by the Ministry of Health between 1 January and September 2020, a 41.5% increase compared to the same period in 2019. -

Determinación De La Recarga Con Isótopos Ambientales En Los Acuíferos De Santa Fe De Antioquia

BOLETÍN DE CIENCIAS DE LA TIERRA Número 24, Noviembre de 2008 Medellín ISSN 0120 3630 DETERMINACIÓN DE LA RECARGA CON ISÓTOPOS AMBIENTALES EN LOS ACUÍFEROS DE SANTA FE DE ANTIOQUIA María Victoria Vélez O. & Remberto Luis Rhenals G. Escuela de Geociencias y Medio Ambiente, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín. [email protected] Recibido para evaluación: 08 de Octubre de 2008 / Aceptación: 04 de Noviembre de 2008 / Recibida versión final: 20 de Noviembre de 2008 RESUMEN La zona del Occidente antioqueño, conformada por los municipios de Santa Fé de Antioquia, Sopetrán, San Jerónimo, Olaya y Liborina, es una de las principales zonas turísticas del departamento de Antioquia. Debido a esto, existe una importante demanda de agua que se ha incrementado con el aumento de la actividad turística propiciada por la construcción del proyecto «Conexión Vial entre los valles de Aburra y del Río Cauca». A pesar que esta zona posee varias fuentes hídricas superficiales, estas no abastecen completamente las necesidades del recurso hídrico ya que están contaminadas por lixiviados y residuos de la actividad agrícola, pecuaria y humana. Esto convierte el agua subterránea en una importante fuente de agua adicional y una gran alternativa para satisfacer la creciente demanda. La Universidad Nacional (2004) hizo un trabajo preliminar donde se identificaron zonas acuíferas con buen potencial para el abastecimiento de agua potable. Para la construcción de un modelo hidrogeológico, condición necesaria para el manejo y aprovechamiento óptimo del agua subterránea, se hace necesario además identificar las zonas de recarga de los acuíferos. Una de las herramientas más ampliamente usadas para este fin son los isótopos ambientales deuterio, H 2 y O 18 .Se presentan en este trabajo los resultados de la utilización de estos isótopos para determinar las zonas de recarga de los acuíferos del Occidente antioqueño. -

The Mineral Industry of Colombia in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF COLOMBIA By David B. Doan Although its mineral sector was relatively modest by world foundation of the economic system of Colombia. The standards, Colombia’s mineral production was significant to its constitution guarantees that investment of foreign capital shall gross domestic product (GDP), which grew by 3.2% in 1997. have the same treatment that citizen investors have. The A part of this increase came from a 4.4% growth in the mining constitution grants the State ownership of the subsoil and and hydrocarbons sector.1 In 1998, however, Colombia ended nonrenewable resources with the obligation to preserve natural the year in recession with only 0.2% growth in GDP, down resources and protect the environment. The State performs about 5% from the year before, the result of low world oil supervision and planning functions and receives a royalty as prices, diminished demand for exports, terrorist activity, and a economic compensation for the exhaustion of nonrenewable decline in the investment stream. The 1998 GDP was about resources. The State believes in privatization as a matter of $255 billion in terms of purchasing power parity, or $6,600 per principle. The Colombian constitution permits the capita. Colombia has had positive growth of its GDP for more expropriation of assets without indemnification. than six decades and was the only Latin American country not The mining code (Decree 2655 of 1988) covers the to default on or restructure its foreign debt during the 1980's, prospecting, exploration, exploitation, development, probably owing in no small part to the conservative monetary beneficiation, transformation, transport, and marketing of policy conducted by an independent central bank. -

Pdf | 319.67 Kb

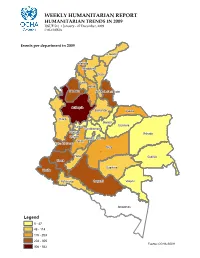

WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Events per department in 2009 La Guajira Atlántico Magdalena Cesar Sucre Bolívar Córdoba Norte de Santander Antioquia Santander Arauca Chocó Boyacá Casanare Caldas Cundinamarca Risaralda Vichada Quindío Bogotá, D.C. To l i m a Valle del Cauca Meta Huila Guainía Cauca Guaviare Nariño Putumayo Caquetá Vaupés Amazonas Legend 5 - 47 48 - 114 115 - 203 204 - 305 Fuente: OCHA-SIDIH 306 - 542 WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Events in 2009 | Weekly trend* 350 325 175 96 132 70 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 0 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 Events in 2009 | Total per department Number of events per category Antioquia 542 Nariño 305 Massacres, Displaceme Forced Cauca 296 125 nt events, recruit., 63 Valle del Cauca 261 Road 81 Córdoba 269 blocks, 55 Norte de Santander 250 Caquetá 225 Arauca 203 Atlántico 157 Armed Tolima 160 conf., 825 Bolivar 150 Meta 146 APM/UXO Bogotá D.C. 109 Victims, Huila 106 670 Cesar 114 Sucre 93 Homicide Putumayo 86 of PP, 417 Risaralda 83 Magdalena 85 Santander 78 Chocó 78 Guaviare 71 La Guajira 68 Kidnappin Vaupés 47 g, 157 Attacks on Caldas 36 civ., 1.675 Quindío 27 Cundinamarca 23 Casanare 22 Boyacá 18 Quindío 12 Vichada 7 Guanía 5 0 300 600 WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN REPORT HUMANITARIAN TRENDS IN 2009 ISSUE 51| 1 January - 27 December, 2009 COLOMBIA Main events in 2009 per month • January: Flood Response Plan mobilised US$ 3.1 million from CERF. -

Aasen -- Constructing Narcoterrorism As Danger.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Constructing Narcoterrorism as Danger: Afghanistan and the Politics of Security and Representation Aasen, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Donald Aasen, 2019. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Constructing Narcoterrorism as Danger: Afghanistan and the Politics of Security and Representation Greg Aasen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2019 1 Abstract Afghanistan has become a country synonymous with danger. Discourses of narcotics, terrorism, and narcoterrorism have come to define the country and the current conflict. However, despite the prevalence of these dangers globally, they are seldom treated as political representations. This project theorizes danger as a political representation by deconstructing and problematizing contemporary discourses of (narco)terrorism in Afghanistan. Despite the globalisation of these two discourses of danger, (narco)terrorism remains largely under-theorised, with the focus placed on how to overcome this problem rather than critically analysing it as a representation. The argument being made here is that (narco)terrorism is not some ‘new’ existential danger, but rather reflects the hegemonic and counterhegemonic use of danger to establish authority over the collective identity. -

Redalyc.Religión Y La Violencia En Documentos De Los Años Cincuenta

Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura ISSN: 0120-2456 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Mesa Hurtado, Gustavo Adolfo Religión y la Violencia en documentos de los años cincuenta en Colombia. Las cartas del Capitán Franco Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, vol. 36, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2009, pp. 65-89 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=127113486004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Religión y la Violencia en documentos de los años cincuenta en Colombia. Las cartas del Capitán Franco Religion and the Violencia in the 1950’s Documents: The Letters of the Captain Franco gustavo adolfo mesa hurtado * Universidad de Antioquia Medellín, Colombia * [email protected] Artículo de investigación. Recepción: 23 de febrero de 2009. Aprobación: 16 de septiembre de 2009. anuario colombiano de historia social y de la cultura * vol. 36, n.º 2 * 2009 * issn 0120-2456 * bogotá - colombia * pags. 65-89 g u s t a V o a d o l F o mesa hurtado resumen Este trabajo presenta una serie de comunicaciones o cartas suscritas en el periodo del “orden neoconservador” en Colombia (1949-1958) por el Capitán Franco, líder del alzamiento liberal del suroeste y occidente antioqueños entre 1949 y 1953. Dichas cartas destacan aspectos de la vida diaria dentro y fuera de la guerra. -

The Drug Trade in Colombia: a Threat Assessment

DEA Resources, For Law Enforcement Officers, Intelligence Reports, The Drug Trade in Colombia | HOME | PRIVACY POLICY | CONTACT US | SITE DIRECTORY | [print friendly page] The Drug Trade in Colombia: A Threat Assessment DEA Intelligence Division This report was prepared by the South America/Caribbean Strategic Intelligence Unit (NIBC) of the Office of International Intelligence. This report reflects information through December 2001. Comments and requests for copies are welcome and may be directed to the Intelligence Production Unit, Intelligence Division, DEA Headquarters, at (202) 307-8726. March 2002 DEA-02006 CONTENTS MESSAGE BY THE ASSISTANT THE HEROIN TRADE IN DRUG PRICES AND DRUG THE COLOMBIAN COLOMBIA’S ADMINISTRATOR FOR COLOMBIA ABUSE IN COLOMBIA GOVERNMENT COUNTERDRUG INTELLIGENCE STRATEGY IN A LEGAL ● Introduction: The ● Drug Prices ● The Formation of the CONTEXT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Development of ● Drug Abuse Modern State of the Heroin Trade Colombia ● Counterdrug ● Cocaine in Colombia DRUG RELATED MONEY ● Colombian Impact of ● Colombia’s 1991 ● Heroin Opium-Poppy LAUNDERING AND Government Institutions Involved in Constitution ● Marijuana Cultivation CHEMICAL DIVERSION ● Opium-Poppy the Counterdrug ● Extradition ● Synthetic Drugs Eradication Arena ● Sentencing Codes ● Money Laundering ● Drug-Related Money ● Opiate Production ● The Office of the ● Money Laundering ● Chemical Diversion Laundering ● Opiate Laboratory President Laws ● Insurgents and Illegal “Self- ● Chemical Diversion Operations in ● The Ministry of ● Asset Seizure -

Second Circular Conference Colombia in the IYL 2015

SECOND ANNOUNCEMENT International Conference \Colombia in the International Year of Light" June 16 - 19, 2015 Bogot´a& Medell´ın,Colombia 1 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Dear Colleagues, The International Conference Colombia in the International Year of Light (IYL- ColConf2015) will be held in Bogot´a,Colombia on 16-17 June 2015, and Medell´ın, Colombia on 18-19 June 2015. IYLColConf2015 is expected to bring together 500- 600 scientists, other professionals, and students engaged to research, development and applications of science and technology of light. You are invited to attend this conference and take part in the discussions about the \state of the art" in this field, in company of world-renowned scientists. Organizers and promoters of this conference include: The Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes), Bogot´a;the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (National University of Colombia), Bogot´aand Medell´ın; the Universidad de Antioquia (University of Antioquia), Medell´ın; the Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales (Colombian Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences); Colombian research groups working on topics related to optical sciences, and academic programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We are honored to host IYLColConf2015 in Bogot´aand Medell´ın,two of the main cities of Colombia, in June 2015. We look forward to seeing you there. Sincerelly yours, On behalf of the Executive Committee, Prof. Jorge Mahecha. Institute of Physics, Universidad de Antioquia. page 2 of 27 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Contents • IYLColConf2015 Committees 3 • General Information and Deadlines 5 • Registration and Support Policy 7 • Further Information 8 • Scientific Program 9 • Conference proceedings 25 • Travel and Transportation 25 • Hotels and Accommodations 25 • Miscellaneous 25 • Sponsors 27 IYLColConf2015 Committees International Advisory Committee Prof. -

Austria University of Vienna All Belgium Catholic University Of

Monash University - Exchange Partners Faculties Minimum GPA/WAM Austria University of Vienna All WAM 65 Belgium Catholic University of Leuven BusEco WAM 70 Brazil Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) of Rio de Janeiro All WAM 70 Brazil Universidade de Brasilia All WAM 70 Brazil State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) Brazil All WAM 70 Brazil University of Sao Paulo Arts WAM 70 Canada Bishop's University All WAM 70 Canada Carleton University All WAM 70 Canada HEC Montreal BusEco GPA 3.0 Canada Queen's University Arts, Science, Engineering, BusEco GPA 2.7 Canada Simon Fraser University All WAM 70 Canada University of British Columbia All except BusEco & Law WAM 85 Canada University of Ottawa BusEco WAM 70 Canada University of Waterloo All WAM 70 Canada York University All except BusEco & Law WAM 70 Canada Osgoode Hall Law School (York University) Law WAM 70 - previous 2 yrs Chile La Pontificia Universidad Catholic de Chile All WAM 70 Chile Universidad Diego Portales All WAM 70 Chile Universidad de Chile All WAM 70 China Peking University All WAM 60 China Shanghai Jiao Tong University All WAM 60 China Sichuan University All WAM 60 China Tsinghua University All WAM 60 China Nanjing University All WAM 60 China Fudan University All WAM 60 China Harbin Institute of Technology All WAM 60 China Sun Yat-Sen University All WAM 60 China Univeristy of Science and Technology of China All WAM 60 China Xi'an Jiaotong University All WAM 60 China Zhejinag University All WAM 60 Colombia University of Antioquia All WAM 70 Denmark Copenhagen Business School -

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties?

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties? John E. Thomas, Jr.* Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................ 1882 II. Narco-Terrorism ......................................................................... 1885 A. History: The Buildup to Current Legislation ...................... 1885 B. Four Cases Demonstrate the Status Quo .............................. 1888 1. United States v. Corredor-Ibague ................................. 1889 2. United States v. Jiménez-Naranjo ................................. 1890 3. United States v. Mohammed.......................................... 1891 4. United States v. Khan .................................................... 1892 III. Drug-Terror Nexus: Necessary? ................................................ 1893 A. The Case History Supports the Nexus ................................. 1894 B. The Textual History Complicates the Issue ......................... 1895 C. The Statutory History Exposes Congressional Error ............ 1898 IV. Conspiracy: Legitimate? ............................................................ 1904 A. RICO Provides an Analogy ................................................. 1906 B. Public Policy Determines the Proper Result ........................ 1909 V. Hypothetical Situations with a Less Forgiving Prosecutor ......... 1911 A. Terrorist Selling Drugs to Support Terror ............................ 1911 B. Drug Dealer Using Terror to Support Drug -

FESTIVAL DE FÚTBOL BABYFÚTBOL COLANTA ZONAL NORTE Y BAJO CAUCA DE ANTIOQUIA SEDE GUADALUPE Noviembre 23 a Diciembre 01 De 2019

FESTIVAL DE FÚTBOL BABYFÚTBOL COLANTA ZONAL NORTE Y BAJO CAUCA DE ANTIOQUIA SEDE GUADALUPE Noviembre 23 a diciembre 01 de 2019 EQUIPOS 1. Corregimiento Bellavista de Donmatías 10. Municipio de Gómez Plata 2. Corregimiento de Ochali de Yarumal 11. Municipio de Guadalupe 3. Corregimiento Palomar Caucasia 12. Municipio de Ituango 4. Corregimiento Puerto López de El Bagre 13. Municipio de San Andrés de Cuerquia 5. Corregimiento San Pablo de Santa Rosa de 14. Municipio de San Pedro de los Milagros Osos 6. Municipio de Caucasia 15. Municipio de Taraza 7. Municipio de Donmatías 16. Municipio de Valdivia 8. Municipio de El Bagre 17. Municipio de Yarumal 9. Municipio de Entrerríos 18. Municipio de Zaragoza GRUPOS Grupo A Grupo B 1. Municipio de Guadalupe 6. Corregimiento San Pablo de Santa Rosa de Osos 2. Corregimiento de Ochali de Yarumal 7. Municipio de Gómez Plata 3. Municipio de Taraza 8. Municipio de Caucasia 4. Municipio de Donmatías 9. Municipio de San Pedro de los Milagros 5. Municipio de Valdivia 10. Corregimiento Palomar Caucasia Grupo C Grupo D 11. Municipio de Zaragoza 15. Municipio de El Bagre 12. Corregimiento Bellavista de Donmatías 16. Municipio de Entrerríos 13. Municipio de Yarumal 17. Municipio de San Andrés de Cuerquia 14. Corregimiento Puerto López de El Bagre 18. Municipio de Ituango PROGRAMACIÓN GENERAL “CORPORACIÓN DEPORTIVA LOS PAISITAS” PRIMERA FECHA DOMINGO, 24 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2019 CANCHA MUNICIPAL DE GUADALUPE 11. Municipio de Zaragoza VS 12. Corregimiento Bellavista de C 8:00 a.m. Donmatías 13. Municipio de Yarumal VS 14. Corregimiento Puerto López de C 9:15 a.m.