Citizenship Performance and Urban Social Space in Bogotá, 1985-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehispanic and Colonial Settlement Patterns of the Sogamoso Valley

PREHISPANIC AND COLONIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF THE SOGAMOSO VALLEY by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal B.A. (Anthropology), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2006 M.A. (Anthropology), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal It was defended on April 12, 2016 and approved by Dr. Marc Bermann, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Olivier de Montmollin, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Robert D. Drennan, Distinguished Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal 2016 iii PREHISPANIC AND COLONIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF THE SOGAMOSO VALLEY Sebastian Fajardo Bernal, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This research documents the social trajectory developed in the Sogamoso valley with the aim of comparing its nature with other trajectories in the Colombian high plain and exploring whether economic and non-economic attractors produced similarities or dissimilarities in their social outputs. The initial sedentary occupation (400 BC to 800 AD) consisted of few small hamlets as well as a small number of widely dispersed farmsteads. There was no indication that these communities were integrated under any regional-scale sociopolitical authority. The population increased dramatically after 800 AD and it was organized in three supra-local communities. The largest of these regional polities was focused on a central place at Sogamoso that likely included a major temple described in Spanish accounts. -

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh CAMPUS: OAKLAND (PITTSBURGH) 2021-22 Factsheet for Incoming Exchange Students CONTACT INFORMATION General Office Information Study Abroad Office, University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh 802 William Pitt Union, 3959 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA ☏ +1 412-648-7413 +1 412-383-1766 [email protected] internationalexchanges.pitt.edu Contact for Incoming & Shawn ALFONSO WELLS (Ms.) Exchange and Panther Program Manager Outgoing Students ☏ +1 412-648-7413 [email protected] Academic Calendar & Fall 2021 Semester Spring 2022 Semester International Student Aug. 15 – 16, 2021 (Tentative) Jan. 11 – 5, 2022 (Tentative) Deadlines Check-in Courses duration Aug. 24 – Dec. 4, 2021 Jan. 11 – Apr. 23, 2022 Final Exams Dec. 7 – 12, 2021 Apr. 26 – May 1, 2022 Nomination Deadlines Application Deadlines Year (Fall & Spring) March 1 March 25 Fall (Semester 1) March 1 March 25 Spring (Semester 2) October 1 October 15 See details: http://internationalexchanges.pitt.edu/deadlines-calendar Application Materials & • Online application. • Passport. Requirements • English Language Requirements. Non-native English speakers must meet one of the minimum requirements: IELTS Band Score 6.5, Duolingo 105 or TOELF iBT 80. Students who score less than 100 on the TOEFL iBT or Band 7.0 on the IELTS must take an additional proficiency test upon arrival. • Transcripts. See details: http://internationalexchanges.pitt.edu/eligibility Tuition Costs & Fees Tuition: No tuition costs. Special Fees: For select courses that require special equipment, such the physical education courses or studio art courses, fees maybe charged. For a list of the courses, please see the “Special Course Related Fees” for the following website here: http://www.registrar.pitt.edu/courseclass.html. -

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement JUNE 19, 2020 One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement 11 A.M. CDT, FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 2982_STUDAFF_CommencementProgram_2020_FRONT.indd 1 6/12/20 12:14 PM UNIVERSITY SEAL AND MOTTO Soon after Northwestern University was founded, its Board of Trustees adopted an official corporate seal. This seal, approved on June 26, 1856, consisted of an open book surrounded by rays of light and circled by the words North western University, Evanston, Illinois. Thirty years later Daniel Bonbright, professor of Latin and a member of Northwestern’s original faculty, redesigned the seal, Whatsoever things are true, retaining the book and light rays and adding two quotations. whatsoever things are honest, On the pages of the open book he placed a Greek quotation from the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 14, translating to The Word . whatsoever things are just, full of grace and truth. Circling the book are the first three whatsoever things are pure, words, in Latin, of the University motto: Quaecumque sunt vera whatsoever things are lovely, (What soever things are true). The outer border of the seal carries the name of the University and the date of its founding. This seal, whatsoever things are of good report; which remains Northwestern’s official signature, was approved by if there be any virtue, the Board of Trustees on December 5, 1890. and if there be any praise, The full text of the University motto, adopted on June 17, 1890, is think on these things. from the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians, chapter 4, verse 8 (King James Version). -

Content of Sessions

10:00 - 11:00 a.m. Register: https://bit.ly/2ZUdDpN Session 1a, Indigenous Perspectives: Ethnographic Travels Around Ethnic Groups in Africa and South America Bilingualism conditions in an indigenous bilingual school in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia: education policies and use of languages at an iku school community, Nicolás David Barbosa Varón, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá The iku or arhuaco is an indigenous ethnic group located at Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, northern Colombia. They have historically been characterized by their resistance and resilience to phenomena of cultural threat derived from colonization and the constitution of a country that has been politically and socially adverse towards indigenous cultures and languages. Within the framework of linguistic conservation, it is established that school education is an important element for the maintenance of ethnic languages, in consequence the iku people began, at the end of 20th century, a process of establishing their own education program. Simunurwa is an iku community close to the town center of Pueblo Bello (Cesar Department), so the contact between indigenous and mestizo people is remarkable; nevertheless, the traditional culture and language remain widespread despite economic, political and cultural external influences. This sociolinguistic research, from an ethnographic approach, proposes the analysis of the state of bilingualism at Simunurwa Indigenous Educational Center, considering the linguistic planning and the use of ikun (indigenous language) and Spanish in different speech situations of the school context. It is identified that in Simunurwa exists a linguistic policy favorable to the indigenous tongue so it maintains its place in the multiple speech contexts; however, in the educational field, the ikun language is at disadvantage compared to Spanish, mainly in terms of literacy. -

Salt Deposits in the UK

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NERC Open Research Archive Halite karst geohazards (natural and man-made) in the United Kingdom ANTHONY H. COOPER British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, Great Britain COPYRIGHT © BGS/NERC e-mail [email protected] +44 (-0)115 936 3393 +44 (-0)115 936 3475 COOPER, A.H. 2002. Halite karst geohazards (natural and man-made) in the United Kingdom. Environmental Geology, Vol. 42, 505-512. This work is based on a paper presented to the 8th Multidisciplinary Conference on Sinkholes and the Engineering and Environmental impact of karst, Louisville, Kentucky, April 2001. In the United Kingdom Permian and Triassic halite (rock salt) deposits have been affected by natural and artificial dissolution producing karstic landforms and subsidence. Brine springs from the Triassic salt have been exploited since Roman times, or possibly earlier, indicating prolonged natural dissolution. Medieval salt extraction in England is indicated by the of place names ending in “wich” indicating brine spring exploitation at Northwich, Middlewich, Nantwich and Droitwich. Later, Victorian brine extraction in these areas accentuated salt karst development causing severe subsidence problems that remain a legacy. The salt was also mined, but the mines flooded and consequent brine extraction caused the workings to collapse, resulting in catastrophic surface subsidence. Legislation was enacted to pay for the damage and a levy is still charged for salt extraction. Some salt mines are still collapsing and the re-establishment of the post-brine extraction hydrogeological regimes means that salt springs may again flow causing further dissolution and potential collapse. -

Human Values of Colombian People. Evidence for the Functionalist Theory of Values

Human values of colombian people. Evidence for the functionalist theory of values Human values of colombian people. Evidence for the functionalist theoryof values Valores Humanos de los Colombianos. Evidencia de la Teoría Funcionalista de los Valores Recibido: Febrero de 201228 de mayo de 2010. Rubén Ardila Revisado: Agosto de 20124 de junio de 2012. National University of Colombia, Colombia Aceptado: Octubre de 2012 Valdiney V. Gouveia Universidad Federal de Paraíba, Brasil Emerson Diógenes de Medeiros Universidad Federal de Piauí, Brasil This paper was supported in part by grant of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development to the second author. Authors are grateful to this agency. Correspondence must be addressed to Rubén Ardila, National University of Colombia. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Resumen The objective of this research work has been to get to El objetivo de esta investigación ha sido conocer la orientación know the axiological orientation of Colombians, and axiológica de los colombianos, y reunir evidencias empíricas gather empirical evidence regarding the suitability of the con respecto a la adecuación de la teoría funcionalista de functionalist theory of values in Colombia, testing its content los valores en Colombia, comprobando sus hipótesis de and structure hypothesis and the psychometric properties contenido y estructura y las propiedades psicométricas de of its measurement (Basic Values Questionnaire BVQ). The su medida (el Cuestionario de Valores Básicos, CVB). El BVQ evaluates sexuality, success, social support, knowledge, CVB evalúa sexualidad, éxito, apoyo social, conocimiento, emotion, power, affection, religiosity, health, pleasure, emoción, poder, afectividad, religiosidad, salud, placer, prestige, obedience, personal stability, belonging, beauty, prestigio, obediencia, estabilidad personal, pertenencia, tradition, survival, and maturity. -

GRUPOS INDÍGENAS EN COLOMBIA Indígenas De Colombia Achagua

GRUPOS INDÍGENAS EN COLOMBIA Indígenas de Colombia Achagua, Amorúa, Andoke, Arhuaco, Awa, Bara, Barasana, Barí, Betoye, Bora, Cañamomo, Carapana, Cocama, Chimila, Chiricoa, Coconuco, Coreguaje, Coyaima-Natagaima, Desano, Dujo, Embera, Embera Katío, Embera-Chamí, Eperara-Siapidara, Guambiano, Guanaca, Guane, Guayabero, Hitnu, Hupdu, Inga, Juhup, Kakua, Kamëntsá, Kankuamo, Karijona, Kawiyarí - Cabiyarí, Kofán, Kogui, Kubeo, Kuiba, Kurripaco, Letuama, Makaguaje, Makuna, Masiguare, Matapí, Miraña, Mokaná, Muinane, Muisca, Nasa - Páez, Nonuya, Nukak, Ocaina, Pasto, Piapoco, Piaroa, Piratapuyo, Pisamira, Puinave, Sáliba, Sánha, Senú, Sikuani, Siona, Siriano, Taiwano, Tanimuka, Tariano, Tatuyo, Tikuna, Totoró, Tsiripu, Tucano, Tule, Tuyuka, Uitoto, U‘wa - Tunebo, Wanano, Waunan, Wayuu, Wiwa, Yagua, Yanacona, Yauna, Yuko, Yukuna, Yuri, Yurutí, PUEBLO ACHAGUA ( ajagua, axagua ) Lengua: Pertenece a la familia lingüística Arawak Ubicación Geográfica Achagua Los Achagua estuvieron esparcidos en algunas sabanas del río Meta entre el río Casanare y el río Ariporo. Actualmente se asientan en los resguardos de la Victoria -Umapo- y en el resguardo del Turpial, jurisdicción del municipio de Puerto López, departamento del Meta, donde conviven con los Piapoco. Población Achagua La población estimada es de 283 personas, repartidas en un perímetro de 3.318 hectáreas. Cultura Achagua Los Achagua, uno de los grupos más numerosos y representativos de la región de la Orinoquia en el momento de la conquista, ocupaban una amplia zona que se extendía desde los Estados de Falcón, Aragua y Coro en Venezuela, hasta territorio colombiano. De acuerdo a las fuentes etnohistóricas, los grupos de la región desarrollaron formas comerciales de intercambio. En particular, los Achagua crearon mecanismos de reciprocidad y cooperación que les permitieron explotar junto con los Sicuani y otros pueblos, microambientes diferentes. -

Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano

COLOMBIAN NATIONALISM: FOUR MUSICAL PERSPECTIVES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Ana Maria Trujillo A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music The University of Memphis December 2011 ABSTRACT Trujillo, Ana Maria. DMA. The University of Memphis. December/2011. Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano. Dr. Kenneth Kreitner, Ph.D. This paper explores the Colombian nationalistic musical movement, which was born as a search for identity that various composers undertook in order to discover the roots of Colombian musical folklore. These roots, while distinct, have all played a significant part in the formation of the culture that gave birth to a unified national identity. It is this identity that acts as a recurring motif throughout the works of the four composers mentioned in this study, each representing a different stage of the nationalistic movement according to their respective generations, backgrounds, and ideological postures. The idea of universalism and the integration of a national identity into the sphere of the Western musical tradition is a dilemma that has caused internal struggle and strife among generations of musicians and artists in general. This paper strives to open a new path in the research of nationalistic music for violin and piano through the analyses of four works written for this type of chamber ensemble: the third movement of the Sonata Op. 7 No.1 for Violin and Piano by Guillermo Uribe Holguín; Lopeziana, piece for Violin and Piano by Adolfo Mejía; Sonata for Violin and Piano No.3 by Luís Antonio Escobar; and Dúo rapsódico con aires de currulao for Violin and Piano by Andrés Posada. -

About the Urban Development of Hallstatt

About the Urban Development of Hallstatt CONTENTS 1. STARTING POINT 2 2. TOPOGRAPHY 3 2.1. Topographical survey 3 The Lake 3 The Mountains 3 The Communes of the Lake of Hallstatt 3 The Market Commune of Hallstatt 3 Names of Streets, Meadows and Marshes 4 2.3. The Morphology of the Villages 4 The Market 4 Lahn 4 3. URBAN DEVELOPMENT 6 3.1 The Development of the Traffic Network 6 The Waterway 6 The Paths 6 The Street 7 The Railway 7 The Pipeline, the so called "Sulzstrenn" 7 3.2. The Evolution of the Buildings 9 3.2.1. The Market 9 The Early History and the Age of Romans 9 The Founding in the Middle Ages 9 The Extension in the 16th Century 9 The Stagnation since the Beginning of the 17th Century until the catastrophic conflagration in 175010 The "Amthof" 10 The Court Chapel 11 The Hospital 11 The Hospital Chapel 11 The "Pfannhaus" and the "Pfieseln" 11 The Recession, Starting in 1750 until the Beginning of Tourism 11 The Flourishing of Tourism 12 3.2.2. Lahn 12 The Roman Ages 12 The Modern Times 12 3.3. The Analysis of the Sites and the Structures 15 3.3.1. The Market 15 The Market Place 16 The Landing Place 16 3.3.2. Lahn 17 The Agricultural Area 17 The Industrial Area 17 The Expansion 17 The Condensing 18 4. ANHANG 19 4.1. Commissions Relation dieses hochen Mittels Hoff Raths Herrn v. Quiex die zu Haalstatt abgebrunnenen Sallz Pfannen betreffend. 19 5. -

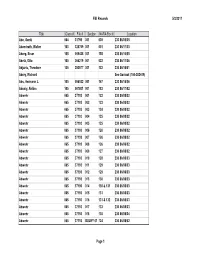

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Second Circular Conference Colombia in the IYL 2015

SECOND ANNOUNCEMENT International Conference \Colombia in the International Year of Light" June 16 - 19, 2015 Bogot´a& Medell´ın,Colombia 1 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Dear Colleagues, The International Conference Colombia in the International Year of Light (IYL- ColConf2015) will be held in Bogot´a,Colombia on 16-17 June 2015, and Medell´ın, Colombia on 18-19 June 2015. IYLColConf2015 is expected to bring together 500- 600 scientists, other professionals, and students engaged to research, development and applications of science and technology of light. You are invited to attend this conference and take part in the discussions about the \state of the art" in this field, in company of world-renowned scientists. Organizers and promoters of this conference include: The Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes), Bogot´a;the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (National University of Colombia), Bogot´aand Medell´ın; the Universidad de Antioquia (University of Antioquia), Medell´ın; the Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales (Colombian Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences); Colombian research groups working on topics related to optical sciences, and academic programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We are honored to host IYLColConf2015 in Bogot´aand Medell´ın,two of the main cities of Colombia, in June 2015. We look forward to seeing you there. Sincerelly yours, On behalf of the Executive Committee, Prof. Jorge Mahecha. Institute of Physics, Universidad de Antioquia. page 2 of 27 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Contents • IYLColConf2015 Committees 3 • General Information and Deadlines 5 • Registration and Support Policy 7 • Further Information 8 • Scientific Program 9 • Conference proceedings 25 • Travel and Transportation 25 • Hotels and Accommodations 25 • Miscellaneous 25 • Sponsors 27 IYLColConf2015 Committees International Advisory Committee Prof. -

Austria University of Vienna All Belgium Catholic University Of

Monash University - Exchange Partners Faculties Minimum GPA/WAM Austria University of Vienna All WAM 65 Belgium Catholic University of Leuven BusEco WAM 70 Brazil Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) of Rio de Janeiro All WAM 70 Brazil Universidade de Brasilia All WAM 70 Brazil State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) Brazil All WAM 70 Brazil University of Sao Paulo Arts WAM 70 Canada Bishop's University All WAM 70 Canada Carleton University All WAM 70 Canada HEC Montreal BusEco GPA 3.0 Canada Queen's University Arts, Science, Engineering, BusEco GPA 2.7 Canada Simon Fraser University All WAM 70 Canada University of British Columbia All except BusEco & Law WAM 85 Canada University of Ottawa BusEco WAM 70 Canada University of Waterloo All WAM 70 Canada York University All except BusEco & Law WAM 70 Canada Osgoode Hall Law School (York University) Law WAM 70 - previous 2 yrs Chile La Pontificia Universidad Catholic de Chile All WAM 70 Chile Universidad Diego Portales All WAM 70 Chile Universidad de Chile All WAM 70 China Peking University All WAM 60 China Shanghai Jiao Tong University All WAM 60 China Sichuan University All WAM 60 China Tsinghua University All WAM 60 China Nanjing University All WAM 60 China Fudan University All WAM 60 China Harbin Institute of Technology All WAM 60 China Sun Yat-Sen University All WAM 60 China Univeristy of Science and Technology of China All WAM 60 China Xi'an Jiaotong University All WAM 60 China Zhejinag University All WAM 60 Colombia University of Antioquia All WAM 70 Denmark Copenhagen Business School