The Colombian Transitional Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A MIXED-USE and WALKABLE BOGOTÁ: a Transit-Oriented Strategy for the City’S First Fixed-Rail Public Transit Corridor

A MIXED-USE AND WALKABLE BOGOTÁ: A Transit-Oriented Strategy for the City’s First Fixed-Rail Public Transit Corridor Cristina Calderón Restrepo A capstone thesis paper submitted to the Executive Director of the Urban & Regional Planning Program at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Professional Studies in Urban & Regional Planning. Faculty Advisor: Harriet Tregoning Academic Advisor: Uwe S. Brandes © Copyright 2018 by Cristina Calderón Restrepo All Rights Reserved 1 ABSTRACT This project explores the creation of an urban planning framework to improve land use near metro stations in Bogotá. This framework will make the new proposed metro stations in Bogotá vibrant community places that attract new investment in housing, office, and retail development. The research looks at lessons-learned from previous transit systems like TransMilenio and how cities like Medellín, Washington, D.C., and Hong Kong have created vibrant and sustainable transit-oriented development (TOD) that Bogotá can replicate in its own way. This research is based on the public proposals for Metro, studies made by the city and multilateral development banks, existing research in other cities, and interviews with leading experts in the field. Through this research I advance new urban development options for Metro stations and their areas of influence. The paper recommends TOD strategies to make transit more democratic and to avoid future gentrification and displacement in station areas. KEYWORDS Transit Oriented Development, Metro, Bogotá, Public Transit, Mixed-Use Development, Health, Pollution, Sustainable Development, Walkable Urbanism, Colombia, Inter-American Development Bank, World Bank, Gentrification, Displacement, TransMilenio, Fixed-Rail RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. -

COLOMBIAN HEARTLANDS Bogota, Medellin, the Cafetera & Cartagena 12 Days Created On: 28 Sep, 2021

Tour Code OACO COLOMBIAN HEARTLANDS Bogota, Medellin, the Cafetera & Cartagena 12 days Created on: 28 Sep, 2021 Day 1 Arrival in Bogota Today we arrive in Bogota, Colombia and transfer to our hotel. Also known as Santa Fe de Bogota, or the 'Athens of the Americas' (owing to Bogotanos' reputation for politeness and civility), Bogota is set at an altitude of over 2600m (8,600 feet) with high ranges of the Cordillera to the east. This captivating urban center has a rich cultural life and beautiful architecture. Like any self-respecting capital city, Bogotá is the country's capital of art, academia, history, culture and government. This is Colombia's beating heart. Overnight in Bogota. Meal Plan: Dinner, if required. Day 2 Bogota: Paloquemao Market, Cerro Monserrate & Gold Museum This morning we will visit the Plaza de Mercado de Paloquemao, the most famous flower and food market in Bogota. This is the focal point where the produce of the Caribbean and Pacific coasts, the fertile Andes and the tropical jungle meld together. The market is divided into sections: flowers; fruit, vegetables and aromatic herbs; and meat and fish. A visit here will engage all of your senses, and provides us with a great insight into Colombian customs and local living in Bogota. Next we take a cable car to Cerro Monserrate. Some amazing views can be had from this great vantage point (weather dependant). Monserrate is crowned with its easily recognizable church and is a place of pilgrimage due to its statue of Senor Caido, the fallen Christ. Cerro de Monserrate is sometimes called the 'mountain-guardian' of Bogota, and has been a place of religious pilgrimage since colonial times. -

Content of Sessions

10:00 - 11:00 a.m. Register: https://bit.ly/2ZUdDpN Session 1a, Indigenous Perspectives: Ethnographic Travels Around Ethnic Groups in Africa and South America Bilingualism conditions in an indigenous bilingual school in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia: education policies and use of languages at an iku school community, Nicolás David Barbosa Varón, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá The iku or arhuaco is an indigenous ethnic group located at Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, northern Colombia. They have historically been characterized by their resistance and resilience to phenomena of cultural threat derived from colonization and the constitution of a country that has been politically and socially adverse towards indigenous cultures and languages. Within the framework of linguistic conservation, it is established that school education is an important element for the maintenance of ethnic languages, in consequence the iku people began, at the end of 20th century, a process of establishing their own education program. Simunurwa is an iku community close to the town center of Pueblo Bello (Cesar Department), so the contact between indigenous and mestizo people is remarkable; nevertheless, the traditional culture and language remain widespread despite economic, political and cultural external influences. This sociolinguistic research, from an ethnographic approach, proposes the analysis of the state of bilingualism at Simunurwa Indigenous Educational Center, considering the linguistic planning and the use of ikun (indigenous language) and Spanish in different speech situations of the school context. It is identified that in Simunurwa exists a linguistic policy favorable to the indigenous tongue so it maintains its place in the multiple speech contexts; however, in the educational field, the ikun language is at disadvantage compared to Spanish, mainly in terms of literacy. -

GRUPOS INDÍGENAS EN COLOMBIA Indígenas De Colombia Achagua

GRUPOS INDÍGENAS EN COLOMBIA Indígenas de Colombia Achagua, Amorúa, Andoke, Arhuaco, Awa, Bara, Barasana, Barí, Betoye, Bora, Cañamomo, Carapana, Cocama, Chimila, Chiricoa, Coconuco, Coreguaje, Coyaima-Natagaima, Desano, Dujo, Embera, Embera Katío, Embera-Chamí, Eperara-Siapidara, Guambiano, Guanaca, Guane, Guayabero, Hitnu, Hupdu, Inga, Juhup, Kakua, Kamëntsá, Kankuamo, Karijona, Kawiyarí - Cabiyarí, Kofán, Kogui, Kubeo, Kuiba, Kurripaco, Letuama, Makaguaje, Makuna, Masiguare, Matapí, Miraña, Mokaná, Muinane, Muisca, Nasa - Páez, Nonuya, Nukak, Ocaina, Pasto, Piapoco, Piaroa, Piratapuyo, Pisamira, Puinave, Sáliba, Sánha, Senú, Sikuani, Siona, Siriano, Taiwano, Tanimuka, Tariano, Tatuyo, Tikuna, Totoró, Tsiripu, Tucano, Tule, Tuyuka, Uitoto, U‘wa - Tunebo, Wanano, Waunan, Wayuu, Wiwa, Yagua, Yanacona, Yauna, Yuko, Yukuna, Yuri, Yurutí, PUEBLO ACHAGUA ( ajagua, axagua ) Lengua: Pertenece a la familia lingüística Arawak Ubicación Geográfica Achagua Los Achagua estuvieron esparcidos en algunas sabanas del río Meta entre el río Casanare y el río Ariporo. Actualmente se asientan en los resguardos de la Victoria -Umapo- y en el resguardo del Turpial, jurisdicción del municipio de Puerto López, departamento del Meta, donde conviven con los Piapoco. Población Achagua La población estimada es de 283 personas, repartidas en un perímetro de 3.318 hectáreas. Cultura Achagua Los Achagua, uno de los grupos más numerosos y representativos de la región de la Orinoquia en el momento de la conquista, ocupaban una amplia zona que se extendía desde los Estados de Falcón, Aragua y Coro en Venezuela, hasta territorio colombiano. De acuerdo a las fuentes etnohistóricas, los grupos de la región desarrollaron formas comerciales de intercambio. En particular, los Achagua crearon mecanismos de reciprocidad y cooperación que les permitieron explotar junto con los Sicuani y otros pueblos, microambientes diferentes. -

Documento FINAL Nota Tecnica Heladas

ACTUALIZACION NOTA TECNICA HELADAS 2012 REALIZADO POR Olga Cecilia González Gómez Carlos Felipe Torres Triana. Contrato N° 201/2012 Subdirección de Meteorología TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. MARCO TEÓRICO …………………………………………………………….……………………………….4 1.1 Definición del fenómeno de heladas ………………………………...............……………………………4 1.2 Clasificación de heladas ……………………………………………………………………………………..4 1.2.1 Helada por advección ………………………………………………………………………………………...4 1.2.2 Helada por evaporación ……………………………………………………………………………………...4 1.2.3 Helada por radiación ………………………………………………………………………………………….4 1.3 Aspectos físicos ………………………………………………………………………………………………5 1.3.1 Balance radiativo ……………………………………………………………………………………………...5 1.3.2 Transmisión de calor …………………………………………………………………………………………6 1.3.3 Variación de la temperatura …………………………………………………………………………………7 1.4. Factores que favorecen las heladas ……………………………………………………………………….8 1.4.1 El vapor de agua ………………………………………………………………………………………………8 1.4.2 El suelo y la vegetación ……………………………………………………………………………………...8 1.4.3 El Viento ………………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 1.4.4 Topografía ………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 1.4.5 Nubosidad y la temperatura vespertina …………………………………………………………………..8 2. COMPORTAMIENTO DE LAS HELADAS EN COLOMBIA ………………………………………………9 2.1 Distribución espacial de las heladas ………………………………………………………………………9 2.2 Distribución temporal de las heladas ……………………………………...…………………….………11 3. REGISTROS HISTÓRICOS O ESTADÍSTICAS ……………………………………………………..…….11 3.1 Promedios de temperatura mínima y temperaturas mínimas absolutas -

MHC Class II Haplotypes of Colombian Amerindian Tribes

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 36, 2, 158-166 (2013) Copyright © 2013, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Research Article MHC Class II haplotypes of Colombian Amerindian tribes Juan J. Yunis1,2,3, Edmond J. Yunis4 and Emilio Yunis3 1Departamento de Patología, Facultad de Medicina e Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Ciudad Universitaria, Bogotá, Colombia. 2Grupo de Identificación Humana e Inmunogenética, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. 3Instituto de Genética, Servicios Médicos Yunis Turbay y Cia, Bogotá, Colombia. 4Brigham and Womens Hospital, Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA. Abstract We analyzed 1041 individuals belonging to 17 Amerindian tribes of Colombia, Chimila, Bari and Tunebo (Chibcha linguistic family), Embera, Waunana (Choco linguistic family), Puinave and Nukak (Maku-Puinave linguistic fami- lies), Cubeo, Guanano, Tucano, Desano and Piratapuyo (Tukano linguistic family), Guahibo and Guayabero (Guayabero Linguistic Family), Curripaco and Piapoco (Arawak linguistic family) and Yucpa (Karib linguistic family). for MHC class II haplotypes (HLA-DRB1, DQA1, DQB1). Approximately 90% of the MHC class II haplotypes found among these tribes are haplotypes frequently encountered in other Amerindian tribes. Nonetheless, striking differ- ences were observed among Chibcha and non-Chibcha speaking tribes. The DRB1*04:04, DRB1*04:11, DRB1*09:01 carrying haplotypes were frequently found among non-Chibcha speaking tribes, while the DRB1*04:07 haplotype showed significant frequencies among Chibcha speaking tribes, and only marginal frequencies among non-Chibcha speaking tribes. Our results suggest that the differences in MHC class II haplotype frequency found among Chibcha and non-Chibcha speaking tribes could be due to genetic differentiation in Mesoamerica of the an- cestral Amerindian population into Chibcha and non-Chibcha speaking populations before they entered into South America. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The experiencing of the Wayuu lucha in a context of uncertainty: Neoliberal multiculturalism, political subjectivities, and preocupación in La Guajira, Colombia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies by Esteban Ferrero Botero Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Postero, Chair Professor Jonathan Friedman Professor Christine Hunefeldt Professor Steven Parish Professor Kristin Yarris 2013 The thesis of Esteban Ferrero Botero is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii DEDICATION For all of us who suffer within and without, consciously or unconsciously, from above and from below. May we all recognize and courageously face the root of our suffering, together. And may we develop true, all-encompassing compassion for ourselves and for others. iv EPIGRAPH Pródiga Guajira en romance y amor, plácida existencia, futuro ensoñador. Naturaleza parida de grandeza preñada en eterno condumio, Su Cerrejón. Singular belleza de ancestros de ilusión, a sus descendientes guardaban cual cofre de valor convincentes, -

![Cronología De La Sabana De Bogotá [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6699/cronolog%C3%ADa-de-la-sabana-de-bogot%C3%A1-pdf-1236699.webp)

Cronología De La Sabana De Bogotá [PDF]

Comparative Archaeology Database University of Pittsburgh URL: http:www.cadb.pitt.edu Cronología de la Sabana de Bogotá Ana María Boada Rivas Investigadora Asociada Universidad de Pittsburgh Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff Fundación Pro-Calima 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Un- ported License. Users of the dataset are requested to credit the source. Contenido Contentido . .ii Agradecimientos . iii 1. Introducción . .1 2. Cronologías del altiplano cundiboyacense . .5 3. Nueva cronología cerámica de la Sabana de Bogotá. 11 4. Periodo Herrera Temprano. 13 Mosquera Rojo Inciso (MRI) . 14 Mosquera Roca Triturada (MRT) . 21 Zipaquirá Desgrasante Tiestos Áspero (ZDTA) . 28 Funza Cuarzo Fino del Herrera Temprano (CF) . 37 5. Periodo Herrera Intermedio . 43 Funza Cuarzo Fino del periodo Herrera Intermedio . 44 Tunjuelo Laminar del periodo Herrera Intermedio (TL) . 58 6. Periodo Herrera Tardío . 61 Funza Cuarzo Fino del periodo Herrera Tardío . 61 Funza Cuarzo Abundante (CA) . 69 Tunjuelo Laminar del periodo Herrera Tardío (TL) . 74 Guatavita Desgrasante Gris del periodo Herrera Tardío (DG) . 88 Desgrasante de Tiestos Sal . 89 7. Periodo Muisca Temprano . 91 Funza Laminar Duro del periodo Muisca Temprano (LD) . 92 Guatavita Desgrasante Gris del periodo Muisca Temprano . .102 Tunjuelo Laminar (TL) y Cuarzo Abundante (CA) del periodo Muisca Temprano . .121 Zipaquirá Desgrasante de Arcillolita Triturada (ZAT) . .123 Guatavita Desgrasante Tiestos del periodo Muisca Temprano (GDT) . .129 Guatavita Desgrasante Tiestos Baño Blanco del periodo Muisca Temprano (GDTBB). .139 8. Periodo Muisca Tardío . .141 Guatavita Desgrasante Gris del periodo Muisca Tardío (GDG) . .142 Guatavita Desgrasante Tiestos del periodo Muisca Tardío (GDT) . .153 Guatavita Desgrasante Tiestos Baño Blanco del periodo Muisca Tardío (GDTBB) . -

9 March 2021 Competition Information Package

BOGOTÁ 2021 ROAD TO TOKYO PARA POWERLIFTING WORLD CUP 1 – 9 March 2021 Competition Information Package World Para Powerlifting Adenauerallee 212-214 Tel. +49 228 2097260 53113 Bonn, Germany Fax +49 228 2097-209 www.WorldParaPowerlifting.org [email protected] Content 1 – 9 March 2021 ............................................................................................................. 1 1 Competition Dates .................................................................................................. 3 2 Competition Entries ................................................................................................ 3 3 Accommodation ..................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Type and cost of rooms: .................................................................................... 3 3.2 Payment procedure ........................................................................................... 4 3.3 Cancellation Policy: ............................................................................................ 4 4 Transportation ........................................................................................................ 4 5 Visa ......................................................................................................................... 4 6 Competition Information ........................................................................................ 5 6.1 Preliminary Competition Programme ............................................................... -

Tunja/Chiquinquirá – Bogotá

PUNTOS DE ATENCIÓN EN LA VÍA DESDE BUCARAMANGA/YOPAL – PARA REFUGIADOS Y MIGRANTES TUNJA/CHIQUINQUIRÁ – BOGOTÁ PUNTO DE ALOJAMIENTO ATENCIÓN PRIMARIA PRIMEROS AUXIIOS ATENCIÓN ATENCIÓN EN SALUD HIDRATACIÓN ESPACIO DE LACTANCIA RESTABLECIMIENTO DE PROTECCIÓN En este mapa encontrarás los servicios que ofrecen organizaciones humanitarias En los diferentes puntos podrás encontrar TEMPORAL EN SALUD EN SALUD PSICOLOGÍA SEXUAL Y REPRODUCTIVA MATERNA CONTACTO FAMILIAR y otros actores a refugiados y migrantes a lo largo de esta ruta, así como la los siguientes servicios gratuitos ubicación de los espacios de atención y sus horarios. ESPACIO PROTECTOR PARA ACCESO A INTERNET Y REFERENCIACIÓN, TRANSPORTE HUMANITARIO ASESORÍA NIÑOS, NIÑAS Y ADOLESCENTES KITS: ALIMENTICIO - BIOSEGURIDAD - HIGIENE - ABRIGO RECARGA DE BATERÍAS INFORMACIÓN Y ORIENTACIÓN PARA EMERGENCIAS MÉDICAS JURÍDICA FUNDACIÓN KARDIOS BRIGADAS ESPACIO DE APOYO ESPACIO DE APOYO ESPACIO DE APOYO ZONA NORTE SUPERCADE SOCIAL CENTRO DISTRITAL DE DERECHOS PUNTO DE ATENCIÓN CENTRO DE CONVIVENCIA M.1 TUNJA Centro 4 5 6 7 8 9 SAN GIL ITINERANTES CHOCONTÁ BOGOTÁ BOGOTÁ INTEGRALES (CEDID) AL MIGRANTE (PAM) SOLIDARIO TRANSITORIO UNIDAD MÓVIL CRCSBC/OIM Cra. 9 # 9 - 79 CHIQUINQUIRÁ Cra. 10 # 17-47 Autopista Norte, Cll 181 # 46 - 33, Barrio Dg. 23 # 69a - 55 BOGOTÁ - Kennedy VILLAVICENCIO YOPAL Nueva Zelandia, Suba. Cra. 13 # 18 - 2 321 497 79 69 CHOCONTÁ Terminal, Salitre Carrera 80 # 43 – 43 sur Calle 17 # 35 - 05 Km. 2.7 vía 312 529 27 50 ACNUR / OIM / Concesión BTS / 312 411 19 44 318 420 18 -

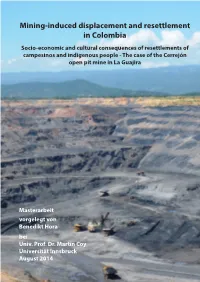

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

DEPARTMENT of CUNDINAMARCA, COLOMBIA - ; R .'

CO-14 fV-iwr iv*?wr. B .i UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROJECT REPORT Colombia Investigations (IR) CO-14 ECONOMIC GEOLOGY OF THE ZIPAQUIRA QUADRANGLE AND. ADJOINING AREA, j- ; % -:. : '..-' ":. .DEPARTMENT OF CUNDINAMARCA, COLOMBIA - ; _ r .' Donald H. MeLaughlin, Jr^ ^, S*. Geological SurvejL ;,: Marino- Arce H.~ , _. Instituta Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras Prepared on behalf-of^ the . i (k^vernment of^ Colombia, and the, ,^~ Agency for International Development, ,O U."S» "Department-of State ; - " " U. S. Geological Survey^ ^ /- OPEN FILE REPORT This .report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for confor mity, with Geological Survey r . _ standards, or nomenclature- . .~ ,- - 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROJECT REPORT Colombia Investigations (IR) CO-14 I ECONOMIC GEOLOGY OF THE ZIPAQUIRA QUADRANGLE AND ADJOINING AREA, DEPARTMENT OF CUDINAMARCA, COLOMBIA by Donald H. McLaughlin I. S. Geological Survey ECONOMIC GEOLOGY OF THE ZIPAQUIRA QUADRANGLE AND ADJOINING AREA, DEPARTMENT OF CUNDINAMARCA, COLOMBIA by Donald H. McLaughlin, Jr. U. S. Geological Survey and Marino Arce H. Institute Nacional de Investigaciones Geol6gico-Mineras CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT............................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 GENERAL GEOLOGY...................................................... 6 Regional tectonic and depositional framework.................... 6 Stratigraphy...................................................