Colombia: Bogota, Eastern Andes and the Magdalena Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basilinna Genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an Evaluation Based on Molecular Evidence and Implications for the Genus Hylocharis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 797-807, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.35769 The Basilinna genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an evaluation based on molecular evidence and implications for the genus Hylocharis El género Basilinna (Aves: Trochilidae): una evaluación basada en evidencia molecular e implicaciones para el género Hylocharis Blanca Estela Hernández-Baños1 , Luz Estela Zamudio-Beltrán1, Luis Enrique Eguiarte-Fruns2, John Klicka3 and Jaime García-Moreno4 1Museo de Zoología, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70- 399, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 2Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70-275, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 3Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA, USA. 4Amphibian Survival Alliance, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected] Abstract. Hummingbirds are one of the most diverse families of birds and the phylogenetic relationships within the group have recently begun to be studied with molecular data. Most of these studies have focused on the higher level classification within the family, and now it is necessary to study the relationships between and within genera using a similar approach. Here, we investigated the taxonomic status of the genus Hylocharis, a member of the Emeralds complex, whose relationships with other genera are unclear; we also investigated the existence of the Basilinna genus. We obtained sequences of mitochondrial (ND2: 537 bp) and nuclear genes (AK-5 intron: 535 bp, and c-mos: 572 bp) for 6 of the 8 currently recognized species and outgroups. -

Bird Ecology, Conservation, and Community Responses

BIRD ECOLOGY, CONSERVATION, AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES TO LOGGING IN THE NORTHERN PERUVIAN AMAZON by NICO SUZANNE DAUPHINÉ (Under the Direction of Robert J. Cooper) ABSTRACT Understanding the responses of wildlife communities to logging and other human impacts in tropical forests is critical to the conservation of global biodiversity. I examined understory forest bird community responses to different intensities of non-mechanized commercial logging in two areas of the northern Peruvian Amazon: white-sand forest in the Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserve, and humid tropical forest in the Cordillera de Colán. I quantified vegetation structure using a modified circular plot method. I sampled birds using mist nets at a total of 21 lowland forest stands, comparing birds in logged forests 1, 5, and 9 years postharvest with those in unlogged forests using a sample effort of 4439 net-hours. I assumed not all species were detected and used sampling data to generate estimates of bird species richness and local extinction and turnover probabilities. During the course of fieldwork, I also made a preliminary inventory of birds in the northwest Cordillera de Colán and incidental observations of new nest and distributional records as well as threats and conservation measures for birds in the region. In both study areas, canopy cover was significantly higher in unlogged forest stands compared to logged forest stands. In Allpahuayo-Mishana, estimated bird species richness was highest in unlogged forest and lowest in forest regenerating 1-2 years post-logging. An estimated 24-80% of bird species in unlogged forest were absent from logged forest stands between 1 and 10 years postharvest. -

Birding the Madeira‐Tapajos Interfluvium 2017

Field Guides Tour Report GREAT RIVERS OF THE AMAZON II: BIRDING THE MADEIRA‐TAPAJOS INTERFLUVIUM 2017 Aug 1, 2017 to Aug 16, 2017 Bret Whitney, Tom Johnson, and Micah Riegner For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Incredible sunsets were met with full checklists, full (and then empty) caipirinhas, and full stomachs back on our riverboat home, the Tumbira. Photo by guide Tom Johnson. An extended voyage into remote areas full of amazing birds but infrequently visited by birders? Yes, please! This two-week tour of the Madeira-Tapajos interfluvium (south of the Amazon) was chock-full of birds and lots of adventure in a comfortable setting with fantastic company. We kicked off this grand adventure in Amazonia in the bustling metropolis of Manaus where we boarded a comfortable and fast speed launch, checking out the meeting of the blackwater Rio Negro and the whitewater Solimoes just downstream from Manaus before blasting off. We shot down the Amazona and then up the Rio Madeira to the riverside town of Borba, cruising past Amazon River Dolphins, Horned Screamers, and Short-tailed Parrots along the way. Borba was our home for three nights, and we used this frontier base as our hub of land-based exploration of the right bank of the Madeira. This was a location notable for the ornithological collections of Natterer, and an area that Bret has visited repeatedly due to its interesting avifauna. Contrasting with a fire-choked season during the tour in 2015, we were fortunate to bird several excellent forest tracts this without issue - well, our endless stream of replacement VW Combi vans notwithstanding! Fortunately, our team on the ground managed our vehicle problems and we were able to continue birding. -

Nature Colombia Trip Report - Eastern Andes & Mid-Magdalena´S Valley 2018

www.naturecolombia.com EASTERN ANDES & MID-MAGDALENA´S VALLEY 3rd March – 8th March 2018 Sword-billed Hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) is characterized by its unusually long bill size; it is the only bird to have a beak longer than the length of its body. As all the pictures in this report, this picture was taken during this trip, in the Hummingbird Observatory Reserve - Bogotá. Nature Colombia Tour Leader: Roger Rodriguez Ardila 2 Nature Colombia Trip Report - Eastern Andes & Mid-Magdalena´s Valley 2018 Colombia is famed for its extraordinary diversity of birds. Thanks to its wide variety of landscapes and climates, Colombia is a megadiverse country with some of the highest biodiversity on the planet. Regardless of size, Colombia holds almost 20% of all birds in the planet (1,944 species, with new species still being discovered). Robert Holt, Lynne and I traveled together for 5 days, visiting some birding sites in the Eastern Andes and the Mid-Magdalena´s Valley looking for some endemic and special birds of this areas. In overall the trip was fast paced, designed to visit as much birding sites as we could of these two very different kind of environments. That also forced us to be in the car for long hours most of the days. We recorded 235 species (47 families), including 11 endemic bird species and 7 near-endemics. This was in spite of the complicated conditions mentioned before. Day Date Morning Afternoon Overnight Blue Suites Hotel - 1 03/03/18 Chingaza National Park Hummingbirds Observatory Bogotá 04/03/18 La Florida Park and El Enchanted Garden and transfer Rio Claro Reserve 2 Tabacal Lagoon to Rio Claro 3 05/03/18 Full day birding at Rio Claro Reserve Rio Claro Reserve 4 06/03/18 Rio Claro Reserve El Paujil Reserve El Paujil Reserve Blue Suites Hotel - 5 07/03/18 El Paujil Reserve Transfer to Bogotá Bogotá TOUR SUMMARY: Day 1. -

A MIXED-USE and WALKABLE BOGOTÁ: a Transit-Oriented Strategy for the City’S First Fixed-Rail Public Transit Corridor

A MIXED-USE AND WALKABLE BOGOTÁ: A Transit-Oriented Strategy for the City’s First Fixed-Rail Public Transit Corridor Cristina Calderón Restrepo A capstone thesis paper submitted to the Executive Director of the Urban & Regional Planning Program at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Professional Studies in Urban & Regional Planning. Faculty Advisor: Harriet Tregoning Academic Advisor: Uwe S. Brandes © Copyright 2018 by Cristina Calderón Restrepo All Rights Reserved 1 ABSTRACT This project explores the creation of an urban planning framework to improve land use near metro stations in Bogotá. This framework will make the new proposed metro stations in Bogotá vibrant community places that attract new investment in housing, office, and retail development. The research looks at lessons-learned from previous transit systems like TransMilenio and how cities like Medellín, Washington, D.C., and Hong Kong have created vibrant and sustainable transit-oriented development (TOD) that Bogotá can replicate in its own way. This research is based on the public proposals for Metro, studies made by the city and multilateral development banks, existing research in other cities, and interviews with leading experts in the field. Through this research I advance new urban development options for Metro stations and their areas of influence. The paper recommends TOD strategies to make transit more democratic and to avoid future gentrification and displacement in station areas. KEYWORDS Transit Oriented Development, Metro, Bogotá, Public Transit, Mixed-Use Development, Health, Pollution, Sustainable Development, Walkable Urbanism, Colombia, Inter-American Development Bank, World Bank, Gentrification, Displacement, TransMilenio, Fixed-Rail RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. -

COLOMBIAN HEARTLANDS Bogota, Medellin, the Cafetera & Cartagena 12 Days Created On: 28 Sep, 2021

Tour Code OACO COLOMBIAN HEARTLANDS Bogota, Medellin, the Cafetera & Cartagena 12 days Created on: 28 Sep, 2021 Day 1 Arrival in Bogota Today we arrive in Bogota, Colombia and transfer to our hotel. Also known as Santa Fe de Bogota, or the 'Athens of the Americas' (owing to Bogotanos' reputation for politeness and civility), Bogota is set at an altitude of over 2600m (8,600 feet) with high ranges of the Cordillera to the east. This captivating urban center has a rich cultural life and beautiful architecture. Like any self-respecting capital city, Bogotá is the country's capital of art, academia, history, culture and government. This is Colombia's beating heart. Overnight in Bogota. Meal Plan: Dinner, if required. Day 2 Bogota: Paloquemao Market, Cerro Monserrate & Gold Museum This morning we will visit the Plaza de Mercado de Paloquemao, the most famous flower and food market in Bogota. This is the focal point where the produce of the Caribbean and Pacific coasts, the fertile Andes and the tropical jungle meld together. The market is divided into sections: flowers; fruit, vegetables and aromatic herbs; and meat and fish. A visit here will engage all of your senses, and provides us with a great insight into Colombian customs and local living in Bogota. Next we take a cable car to Cerro Monserrate. Some amazing views can be had from this great vantage point (weather dependant). Monserrate is crowned with its easily recognizable church and is a place of pilgrimage due to its statue of Senor Caido, the fallen Christ. Cerro de Monserrate is sometimes called the 'mountain-guardian' of Bogota, and has been a place of religious pilgrimage since colonial times. -

N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1

1 FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO CHECK-LIST OF THE BIRDS OF YANACOCHA N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius R 2 Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 4 Andean Teal Anas andium 5 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 7 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 8 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 9 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 10 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus R Sharp-shinned Hawk (Plain- 11 breasted Hawk) Accipiter striatus U 12 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 13 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 14 Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus 15 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 16 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous 17 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus U 18 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula R 19 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma U 20 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens VR 21 Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Attagis gayi 22 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda R 23 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii VR 24 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni FC 25 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis U 26 Noble Snipe Gallinago nobilis 27 Jameson's Snipe Gallinago jamesoni 28 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 29 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagoienas fasciata FC 30 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 31 Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 32 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi R 33 White-throated Quail-Dove Zentrygon frenata U 34 Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata U 35 Barn Owl Tyto alba 36 White-throated Screech-Owl Megascops -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Volume 92 Issue 4 Jul-Aug 2015

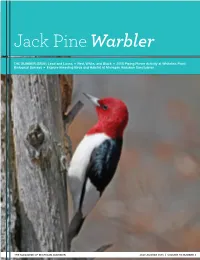

Jack Pine Warbler THE SUMMER ISSUE: Lead and Loons Red, White, and Black 2015 Piping Plover Activity at Whitefish Point Biological Surveys Explore Breeding Birds and Habitat at Michigan Audubon Sanctuaries THE MAGAZINE OF MICHIGAN AUDUBON JULY-AUGUST 2015 | JackVOLUME Pine 92Warbler NUMBER 1 4 Cover Photo Red-headed Woodpecker Photographer: Roger Eriksson The photo was taken from Roger’s vehicle on May 3, 2013 at Tawas Point State Park. Iosco County is a great place to observe this beautiful woodpecker through- out the year. One day this past winter, 54 Red-headed Woodpeckers were seen all around Sand Lake, making CONTACT US Iosco County the Red-headed Woodpecker capital of By mail: Michigan. 2310 Science Parkway, Suite 200 Okemos, MI 48864 The camera body was a Canon EOS-7D attached to a Canon EF 800mm f5.6L IS lens. Shutter speed: 1/1250 By visiting: seconds. Aperture: f 6.3. ISO: 400, +2/3 Exposure Suite 200 compensation. 2310 Science Parkway Okemos, MI 48864 Phone 517-580-7364 Mon.–Fri. 9 AM–5 PM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Contents Jonathan E. Lutz [email protected] Features Columns Departments STAFF 2 8 1 Wendy Tatar Lead and Loons MBS: Celebrating Birders Program Coordinator Executive Director’s Letter [email protected] Kristin Phillips Marketing and Communications Coordinator [email protected] 5 9 4 Biological Surveys Explore Chapter Spotlight: Sable New Members Rachelle Roake Breeding Birds and Habitat Dunes Audubon Society Conservation Science Coordinator at Michigan Audubon [email protected] Sanctuaries 10 Special Thanks for Tawas EDITOR Point Birding Festival Laura Julier [email protected] PRODUCTION 6 11 12–13 Kristin Phillips Red, White, and Black 2015 Piping Plover Activity Calendar Marketing and Communications Coordinator at Whitefish Point Announcements [email protected] ADVERTISING Guidelines available on request. -

Colombia 1 000 Birds Mega Tour II 21St November to 19Th December 2014 (29 Days)

Colombia 1 000 Birds Mega Tour II 21st November to 19th December 2014 (29 days) Lance-tailed Manakin by Dennis Braddy Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Rob Williams Trip Report - RBT Colombia Mega II 2014 2 An early start on day 1 saw us heading to Mundo Nuevo. Our first stop en route produced a flurry of birds including Northern Mountain Cacique, Golden-fronted Whitestart, Barred Becard, Mountain Elaenia and a Green-tailed Trainbearer feeding young at a nest. We continued up to the altitude where the endemic Flame-winged Parakeets breed and breakfasted while we awaited them. We were rewarded with great scope looks at this threatened species. The area also gave us a flurry of other birds including Scarlet-bellied Mountain Tanager, Rufous-breasted Chat- Tyrant, Pearled Treerunner and Smoke-coloured Pewee. We continued up to the edge of the paramo and birded a track inside Chingaza National Park. Activity was low but we persisted and were rewarded with a scattering of birds including Glossy, Masked and Bluish Flowerpiercers, Slaty Brush Finch, Glowing and Coppery-bellied Pufflegs, and Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant. The endemic Bronze-tailed Thornbill only gave frustrating brief flyby views. Great looks however were had of the endemic Pale-bellied Tapaculo, singing from surprisingly high up in a bush. The track back down gave us Rufous Wren, Superciliated and Black-capped Hemispingus and Tourmaline Sunangel. Further down the road a Buff- breasted Mountain Tanager and some Beryl-spangled Tanagers were found before we headed back to La Calera. After lunch in a local restaurant we headed to the Siecha gravel pits. -

University Babeù-Bolyai) from Cluj-Napoca (Romania

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii i comunicri. tiinele Naturii, Tom. XXV/2009 ISSN 1454-6914 THE EXOTIC BIRDS’ COLLECTION OF THE ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM (UNIVERSITY BABE-BOLYAI) FROM CLUJ-NAPOCA (ROMANIA) ANGELA PETRESCU, DELIA CEUCA Abstract. We present the bird collection catalogue of the world fauna from the patrimony of the Zoological Museum of Cluj (founded in 1859). The studied collection includes 221 specimens belonging to 172 species, 59 families, 18 orders. Especially, we mention a small hummingbird collection made of 45 specimens, 38 species; some endemic species, three from Brazil (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) and Apteryx oweni (New Zealand). Also, the collection includes other distinguished species as: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Keywords: catalogue, collection, exotic bird, museum, Cluj (Romania). Rezumat. Colecia de psri exotice a Muzeului Zoologic (Universitatea Babe-Bolyai) din Cluj (România). Prezentm catalogul coleciei de psri din fauna mondial din patrimoniul Muzeului de Zoologie din Cluj (infiinat în 1859). Colecia studiat; cuprinde 221 de exemplare încadrate în 172 de specii, 59 de familii, 18 ordine. Remarcm în mod deosebit o mic colecie de colibri alctuit din 45 de exemplare, 38 de specii; câteva endemite, trei din Brazilia (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) i Apteryx oweni (Noua Zeeland). Colecia conine i alte specii deosebite ca: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Cuvinte cheie: catalog, colecie, psari, fauna mondial, muzeu, Cluj (România). INTRODUCTION The Zoological Museum of Cluj belongs to the ,,Babe-Bolyai’’ University and it was founded in 1860; it was only one part of the Museum of Transylvanian Society.