Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Giant Hummingbird from Paramo De Chingaza, Colombia.-On 10 October 1981, During an Ornithological Survey at 3250 M Elev

GENERAL NOTES 661 E. nigrivestis is timed to coincide with flowering of P. huigrensis (and other plants) which bloom seasonally at lower elevations. The general ecology of E. nigrivestis is similar to that recorded for the closely related species, the Glowing Puffleg (E. vextitus)(Snow and Snow 1980). Snow and Snow (1980) observed E. vestitus feeding principally at plants of similar general morphology (straight tubular corollas 10-20 mm in length) in similar taxonomic groups (Cnvenclishia; Ericaceae more often than Palicourea; Rubiaceae for E. vestitus). Territoriality in E. vestitus was pronounced while this was only suggested in the male E. nigrivestis we observed, perhaps a seasonal effect. Finally E. vestitus, like E. nigrivestis, did not occur in tall forested habitats at similar elevations (Snow and Snow [1980] study at 2400-2500 m). The evidence presented here suggests that the greatly restricted range of E. nigrivestis is not due to dietary specializations. Male nectar sources are from a broad spectrum of plants, and the principal food plant of both sexes, P. huigrensis, is a widespread Andean species. Nesting requirements of E. nigrivestis may still be threatened with extinction through habitat destruction, especially if the species requires specific habitats of natural vegetation at certain times of year, such as that found on nude ridge crests. The vegetation on nudes in particular is rapidly disappearing because nudes provide flat ground for cultivation in otherwise pre- cipitous terrain. In light of its restricted range and the threat of habitat destruction resulting from such close proximity to a major urban center, Quito, we consider E. -

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands

Ecuador & The Galapagos Islands Naturetrek Tour Report 14 - 30 January 2008 Report compiled by Lelis Navarrete Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador & The Galapagos Islands Tour Leader: Lelis Navarrete Participants: Richard Ball Ann Ball Avril Wells Elizabeth Savage Anthony Bourne Margaret Williams Richard Ratcliffe Helen Lewis John Lewis Mary Brunning Alan Brunning Aileen Alderton Bridget Howard Terry Bate Clive Bate Day 1 Monday 14th January Only Ann and Richard were in the Mercure Hotel waiting for the group but unfortunately the British Airways plane had some problems with the brakes and the captain decided that they would change planes before starting from Heathrow airport, as a result the connection with American Airline flight was missed in Miami, the group had to stay overnight in the Marriott Hotel in Miami to get the flights from the following day. Day 2 Tuesday 15th January Terry and Clive arrived around 8:30 to Mercure Hotel and the rest arrived close to mid-night. Day 3 Wednesday 16th January A very early start to catch our flight to Galapagos Islands, the weather conditions had us leaving half an hour than the scheduled time but we arrive in Baltra airport slightly before 11:00 AM, then transfer to the “Cachalote” and sail to Itabaca Channel for a short stop to get supplies, later on we sailed to Islas Plazas arriving into South Plaza near 3:30 PM for our first land visit; slightly after 10:00 PM we sailed to San Cristobal Island. -

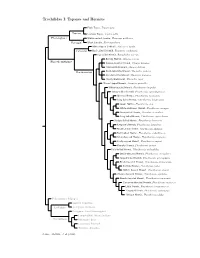

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Bird Ecology, Conservation, and Community Responses

BIRD ECOLOGY, CONSERVATION, AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES TO LOGGING IN THE NORTHERN PERUVIAN AMAZON by NICO SUZANNE DAUPHINÉ (Under the Direction of Robert J. Cooper) ABSTRACT Understanding the responses of wildlife communities to logging and other human impacts in tropical forests is critical to the conservation of global biodiversity. I examined understory forest bird community responses to different intensities of non-mechanized commercial logging in two areas of the northern Peruvian Amazon: white-sand forest in the Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserve, and humid tropical forest in the Cordillera de Colán. I quantified vegetation structure using a modified circular plot method. I sampled birds using mist nets at a total of 21 lowland forest stands, comparing birds in logged forests 1, 5, and 9 years postharvest with those in unlogged forests using a sample effort of 4439 net-hours. I assumed not all species were detected and used sampling data to generate estimates of bird species richness and local extinction and turnover probabilities. During the course of fieldwork, I also made a preliminary inventory of birds in the northwest Cordillera de Colán and incidental observations of new nest and distributional records as well as threats and conservation measures for birds in the region. In both study areas, canopy cover was significantly higher in unlogged forest stands compared to logged forest stands. In Allpahuayo-Mishana, estimated bird species richness was highest in unlogged forest and lowest in forest regenerating 1-2 years post-logging. An estimated 24-80% of bird species in unlogged forest were absent from logged forest stands between 1 and 10 years postharvest. -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands - including Sacha Lodge Extension Naturetrek Tour Report 10 August – 1 September 2015 Galapagos Penguin Marbled Ray Giant Tortoise Giant Tortoise Sally Lightfoot Crab Report kindly compiled by tour clients Margaret and Malcolm Rittman Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands - including Sacha Lodge Extension Tour leaders: Galapagos - Juan Tapia Quito – Esteban Romero and George This report has been compiled by tour participants Margaret and Malcolm Rittman. Fifteen of us were on the Galapagos trip, and eight took the extension to Sacha Lodge. The daily details record highlights of the day, and a full sightings list, excluding marine life and plants, can be found at the end of the report. Day 1 Monday 10th August UK to Quito After the long journey from home to Quito, we were met by Esteban, our Quito guide, who took us to the Hotel Dann Carlton. On the journey he told us about the social and economic history of the country and how it had made a u-turn from the brink of bankruptcy, although there was still much poverty to be seen. Day 2 Tuesday 11th August Quito Weather: Hot and mostly sunny After a good night’s sleep and a good breakfast, Esteban met us with a bus and took us for a cultural trip around Quito, visiting a number of churches and cathedrals, the Presidential Palace and the main plaza. We had free time in the afternoon and options included staying in the city, going even higher on the cable car, or visiting the botanical gardens or a cultural museum. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

Galápagos Natural History Extravaganza

GALÁPAGOS NATURAL HISTORY EXTRAVAGANZA 21 NOVEMBER – 02 DECEMBER 2021 20 NOVEMBER – 01 DECEMBER 2022 19 – 30 NOVEMBER 2023 Red-footed Booby is one of three booby species likely to be found on this trip. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Galapagos: Natural History Extravaganza Just 483 years ago the first man stepped onto the Galápagos Islands and marveled at this living laboratory. Today we continue to be awestruck by this constantly changing archipelago. As the Nazca Plate moves and new islands are formed, evolution is illustrated up close and personal. Visiting the Galápagos archipelago is a dream for all naturalists. From Quito we will fly to the island of Baltra. We then will make our way to our home for the next eight days, the Samba, a spacious and luxuriously designed motor sailing yacht with wide open and shaded sun decks, a fully stocked bar, and a library. The abundant marine life that visits these waters year-round, the Marine Iguanas that rule the rocky coastlines, and of course a unique group of birds make it easy to understand why this trip is a must for birders and natural history buffs. Some of the Galápagos specials that we hope to find on this trip include Galapagos Penguin, Waved Albatross, Galapagos Shearwater, Wedge-rumped and Elliot’s Storm Petrels, Magnificent Frigatebird, Nazca, Red-footed, and Blue-footed Boobies, Lava Heron, Galapagos Hawk, Lava Gull, Galapagos Martin, Galapagos Flycatcher, Vermilion Flycatcher, Galapagos, Floreana, San Cristobal, and Espanola Mockingbirds, Vegetarian Finch, Woodpecker Finch, Common Cactus Finch, Green Warbler-Finch, Large and Small Tree Finches, Small and Medium Ground Finches, and Mangrove Finch. -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Biota Neotropica ISSN 1806-129X English Vol 8 N 3

biota neotropica ISSN 1806-129X english vol 8 n 3 Biota Neotropica is a scientific journal of the Program BIOTA/FAPESP - The Virtual Institute of Biodiversity that publishes the results of original research work, associated or not to the program, that involve characterization, conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in the Neotropical region. Biota Neotropica is an eletronic journal which is available free at the following site http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br This hardcopy of Biota Neotropica has been deposited in reference libraries to fulfill the requirements of the Botanical and Zoological Nomenclatural Codes. Biota Neotrop., vol. 8, no. 3, Jul./Set. 2008 Biota Neotropica, Biota/Fapesp – O Instituto Virtual da Biodiversidade vol. 8, n. 3 (2008) Campinas, Centro de Referência em Informação Ambiental, 2008. Quarterly Portuguese and English publication ISSN: 1806-129X (English Version-Printed) Biodiversity – Periodical CDD-639-9 Desktop Publishing www.cubomultimidia.com.br http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br editora editora editora editora editora editora Biota Neotrop., vol. 8, no. 3, Jul./Set. 2008 Editorial Biodiversity and climate change in the Neotropical region. The isolation of South America from Central America and Africa during the Tertiary Period left a strong imprint on the biota of the Neotropics. For almost 100 million years Neotropical flora, fauna and microorganisms evolved in completely isolation. The emergence of a continuous land bridge, 3 Ma years ago, between Central and South America is well documented and is demonstrated by the arrival of temperate elements in South American highlands and concurrent appearance of South American taxa in Central America. There is strong evidence of displacement of the Neotropical fauna, especially mammals, by northern immigrants, but the same is not observed in relation to plants. -

Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F

1 Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F. Cisneros-Heredia 4 5 Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Laboratorio de Zoología 6 Terrestre & Museo de Zoología, Quito 170901, Ecuador 7 8 King’s College London, Department of Geography, London, UK 9 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 Introduction 15 Movement of propagules of a species from its current range to a new area—i.e., extra-range 16 dispersal—is a natural process that has been fundamental to the development of biogeographic 17 patterns throughout Earth’s history (Wilson et al. 2009). Individuals moving to new areas usually 18 confront a different set of biotic and abiotic variables, and most dispersed individuals do not 19 survive. However, if they are capable of surviving and adapting to the new conditions, they may 20 establish self-sufficient populations, colonise the new areas, and even spread into nearby 21 locations (Mack et al. 2000). In doing so, they will produce ecological transformations in the 22 new areas, which may lead to changes in other species’ populations and communities, speciation 23 and the formation of new ecosystems (Wilson et al. 2009). 24 25 Human extra-range dispersals since the Pleistocene have produced important distribution 26 changes across species of all taxonomic groups. Along our prehistory and history, we have aided 27 other species’ extra-range dispersals either by deliberate translocations or by ecological 28 facilitation due to habitat changes or modification of ecological relationships (Boivin et al. 29 2016).