Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-Conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

A Giant Hummingbird from Paramo De Chingaza, Colombia.-On 10 October 1981, During an Ornithological Survey at 3250 M Elev

GENERAL NOTES 661 E. nigrivestis is timed to coincide with flowering of P. huigrensis (and other plants) which bloom seasonally at lower elevations. The general ecology of E. nigrivestis is similar to that recorded for the closely related species, the Glowing Puffleg (E. vextitus)(Snow and Snow 1980). Snow and Snow (1980) observed E. vestitus feeding principally at plants of similar general morphology (straight tubular corollas 10-20 mm in length) in similar taxonomic groups (Cnvenclishia; Ericaceae more often than Palicourea; Rubiaceae for E. vestitus). Territoriality in E. vestitus was pronounced while this was only suggested in the male E. nigrivestis we observed, perhaps a seasonal effect. Finally E. vestitus, like E. nigrivestis, did not occur in tall forested habitats at similar elevations (Snow and Snow [1980] study at 2400-2500 m). The evidence presented here suggests that the greatly restricted range of E. nigrivestis is not due to dietary specializations. Male nectar sources are from a broad spectrum of plants, and the principal food plant of both sexes, P. huigrensis, is a widespread Andean species. Nesting requirements of E. nigrivestis may still be threatened with extinction through habitat destruction, especially if the species requires specific habitats of natural vegetation at certain times of year, such as that found on nude ridge crests. The vegetation on nudes in particular is rapidly disappearing because nudes provide flat ground for cultivation in otherwise pre- cipitous terrain. In light of its restricted range and the threat of habitat destruction resulting from such close proximity to a major urban center, Quito, we consider E. -

Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands

Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands Darwin Anegada BAP 2006 Page We dedicate this document to the people of Anegada; the stewards of Anegada’s biodiversity and to Raymond Walker of the BVI National Parks Trust who tragically died after a very short illness during the course of this project. This report should be cited as: McGowan A., A.C.Broderick, C.Clubbe, S.Gore, B.J.Godley, M.Hamilton, B.Lettsome, J.Smith-Abbott, N.K.Woodfield. 2006. Darwin Initiative Action Plan for the Coastal Biodiversity of Anegada, British Virgin Islands. 13 pp. Available online at: http://www.seaturtle.org/mtrg/projects/anegada/ Darwin Anegada BAP 2006 Page 2 1. Introduction It well known that Anegada has globally important biodiversity. Indeed, biodiversity is the basis for most livelihoods; supporting fisheries and leading to the attractiveness that is such a draw to visitors. Over the last three years (2003-2006), a project was undertaken on Anegada with a wide range of activities focussing towards this Biodiversity Action Plan. From the outset it was known that the island hosts a globally important coral reef system, regionally significant populations of marine turtles, is of regional importance to birds and supports globally important endemic plants. The project arose following the encouragement of Anegada community members and subsequent extensive consultation between Dr. Godley (University of Exeter) and heads of BVI Conservation and Fisheries Department (CFD) and BVI National Parks Trust (NPT) who requested that funding be sourced for a project which: 1. Allowed the coastal biodiversity of Anegada to be assessed; 2. -

Rare Birds of California Now Available! Price $54.00 for WFO Members, $59.99 for Nonmembers

Volume 40, Number 3, 2009 The 33rd Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2007 Records Daniel S. Singer and Scott B. Terrill .........................158 Distribution, Abundance, and Survival of Nesting American Dippers Near Juneau, Alaska Mary F. Willson, Grey W. Pendleton, and Katherine M. Hocker ........................................................191 Changes in the Winter Distribution of the Rough-legged Hawk in North America Edward R. Pandolfino and Kimberly Suedkamp Wells .....................................................210 Nesting Success of California Least Terns at the Guerrero Negro Saltworks, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2005 Antonio Gutiérrez-Aguilar, Roberto Carmona, and Andrea Cuellar ..................................... 225 NOTES Sandwich Terns on Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico Enriqueta Velarde and Marisol Tordesillas ...............................230 Curve-billed Thrasher Reproductive Success after a Wet Winter in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona Carroll D. Littlefield ............234 First North American Records of the Rufous-tailed Robin (Luscinia sibilans) Lucas H. DeCicco, Steven C. Heinl, and David W. Sonneborn ........................................................237 Book Reviews Rich Hoyer and Alan Contreras ...........................242 Featured Photo: Juvenal Plumage of the Aztec Thrush Kurt A. Radamaker .................................................................247 Front cover photo by © Bob Lewis of Berkeley, California: Dusky Warbler (Phylloscopus fuscatus), Richmond, Contra Costa County, California, 9 October 2008, discovered by Emilie Strauss. Known in North America including Alaska from over 30 records, the Dusky is the Old World Warbler most frequent in western North America south of Alaska, with 13 records from California and 2 from Baja California. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Kurt A. Radamaker of Fountain Hills, Arizona: Aztec Thrush (Ridgwayia pinicola), re- cently fledged juvenile, Mesa del Campanero, about 20 km west of Yecora, Sonora, Mexico, 1 September 2007. -

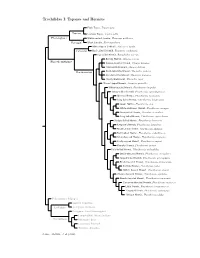

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

List of and Notes on the Birds of the Iles Des Saintes, French West Indies

LIST OF AND NOTES ON THE BIRDS OF THE ILES DES SAINTES, FRENCH WEST INDIES CHARLES VAURIE LES Saintes,a small archipelagothat lies south of Guadeloupe,has seldolnbeen visited by ornithologists.No list of its birdsseems to have beenpublished, although, to besure, 25 specieshave been mentioned froin theseislands by Noble (1916), Bond (1936, 1956), Danforth(1939), or Pinchonand Bon Saint-Come(1951). Three of thesewere recorded on doubtfulevidence and, pendingconfirmation, should be deletedfrom the list. Nineteen of the remaining 22 and an additional five were observedby me on 2-5 July 1960,when Mrs. Vaurie and I visitedthe FrenchWest Indiesfor the AmericanMuseum of Natural History. The speciesmentioned by Noble and Danforth were incorporatedin their reportson the birdsof Guadeloupe,those cited by Bondor Pinchonand Bon Saint-Comein generalworks on the birds of the West Indies. The birds reportedso far are listedbelow with a few notes. I aln grateful to James Bond for his very helpful advice, Eugene Eisenmannfor readingthe manuscript,and to the Gendarmerieof Basse Terre and Terre-de-haut for arranging our visit as there is no hotel in Les Saintes. Les Saintesare of volcanicorigin and are separatedfrom the Basse Terre in Guadeloupeby a stormychannel seven miles wide. They con- sist of two relativelylarge islandscalled Terre-de-bas and Terre-de-haut, the only islandsinhabited, and of six small islandsor islets, some of which appear to be the sites of sea-bird colonies. One of these, called La Redonde,lies only 300 metersoff Terre-de-hautbut, unfortunately, is quite inaccessibleas it risesperpendicularly out of the sea to a height of 46 metersand is poundedby huge waves that rise to nearly half its height. -

THE RAVENS Newsletter Southwestern New Mexico Audubon Society Is a Chapter of National Audubon Society, Inc

THE RAVENS Newsletter Southwestern New Mexico Audubon Society is a Chapter of National Audubon Society, Inc. swnmaudubon.org January — February 2018 Vol. 51, No. 1 JANUARY 5 PROGRAM FEBRUARY 2 PROGRAM Puffbirds, Jacamars, and Marmosets: GOLDEN EAGLES: 4 Months as a Nature Guide in Brazil Natural History & Stories From the Field SWNM Audubon Society will Megan Ruehmann is the featured speaker present a program by Jarrod at the Friday Feb. 2 monthly Audubon Swackhamer who recently program. The program will begin at 7:00 pm spent three and a half months in room 219 of WNMU’s Harlan Hall at 12th as a nature guide at Cristali- and Alabama streets. no Lodge in a 44-square mile For one of our largest and wide-ranging private rainforest reserve in raptors in the United States, observations the southern Amazon of Golden eagles come infrequently and state of Mato Grosso, are always a special treat for birders. This Brazil. National Geo- species, which has the same protection as the Bald eagle graphic Traveler rat- under the Bald and Golden eagle Protection Act, is at the forefront of conservation issues in the western United ed it as one of 25 best States. Megan will examine their natural history, current eco-lodges in the world. research topics, and take a look at a couple stories from He also spent a couple of the field, including our local celebrity Golden eagle “Thor”. weeks in the biodiverse Megan is a wildlife biologist by training and has made coastal Atlantic Forest. Blue and Yellow Macaws ornithology her focus for over 15 years. -

Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Jay F. Storz Publications Papers in the Biological Sciences 11-2012 Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds Michael T. Grispo University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Chandrasekhar Natarajan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Joana Projecto-Garcia University of Nebraska–Lincoln Hideaki Moriyama University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Roy E. Weber Aarhus University, Denmark See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz Grispo, Michael T.; Natarajan, Chandrasekhar; Projecto-Garcia, Joana; Moriyama, Hideaki; Weber, Roy E.; and Storz, Jay F., "Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds" (2012). Jay F. Storz Publications. 61. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jay F. Storz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Michael T. Grispo, Chandrasekhar Natarajan, Joana Projecto-Garcia, Hideaki Moriyama, Roy E. Weber, and Jay F. Storz This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ bioscistorz/61 Published in Journal of Biological Chemistry 287:45 (November 2, 2012), pp. 37647-37658; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375600 Copyright © 2012 The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc. -

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

Bolivia: the Andes and Chaco Lowlands

BOLIVIA: THE ANDES AND CHACO LOWLANDS TRIP REPORT OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2017 By Eduardo Ormaeche Blue-throated Macaw www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Bolivia, October/November 2017 Bolivia is probably one of the most exciting countries of South America, although one of the less-visited countries by birders due to the remoteness of some birding sites. But with a good birding itinerary and adequate ground logistics it is easy to enjoy the birding and admire the outstanding scenery of this wild country. During our 19-day itinerary we managed to record a list of 505 species, including most of the country and regional endemics expected for this tour. With a list of 22 species of parrots, this is one of the best countries in South America for Psittacidae with species like Blue-throated Macaw and Red-fronted Macaw, both Bolivian endemics. Other interesting species included the flightless Titicaca Grebe, Bolivian Blackbird, Bolivian Earthcreeper, Unicolored Thrush, Red-legged Seriema, Red-faced Guan, Dot-fronted Woodpecker, Olive-crowned Crescentchest, Black-hooded Sunbeam, Giant Hummingbird, White-eared Solitaire, Striated Antthrush, Toco Toucan, Greater Rhea, Brown Tinamou, and Cochabamba Mountain Finch, to name just a few. We started our birding holiday as soon as we arrived at the Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, birding the grassland habitats around the terminal. Despite the time of the day the airport grasslands provided us with an excellent introduction to Bolivian birds, including Red-winged Tinamou, White-bellied Nothura, Campo Flicker, Chopi Blackbird, Chotoy Spinetail, White Woodpecker, and even Greater Rhea, all during our first afternoon.