Masterarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociolinguistics (ENG510)

Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Sociolinguistics (ENG510) ___________________________________________________________________________________ ©Copyright Virtual University of Pakistan 1 Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Table of Contents Lesson No. Lesson Title Topics Pg. No. INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLINGUISTICS What is Sociolinguistics? 001 8-9 Some Definitions of Sociolinguistics 002 9 Lesson No. 1 Sociolinguistics and Linguistics 003 9-10 Sociolinguistics and the Sociology of Language 004 10 Sociolinguistics and Other Disciplines 005 10-11 SOCIOLINGUISTIC PHENOMENA Sociolinguistic Phenomena and an Imaginary World 006 12-13 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real but Exotic World 007 13-14 Lesson No. 2 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real and Familiar World 008 15 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and We 009 15-16 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and the Changing World 010 16 SOCIOLINGUISTICS AND VARIETIES OF LANGUAGE The Question of Varieties of Language in Sociolinguistics 011 17-18 Lesson No. 3 What Are Linguistics Items? 012 18 The Terms- Variety and Lect 013 18 Types and Significance of Varieties of Language 014 19 Attitude towards Language Varieties 015 19 SPEECH COMMUNITIES What Are Speech Communities? 016 20 Some Definitions of Speech Communities 017 21 Lesson No. 4 Intersecting Communities 018 21-22 Rejecting the Idea of Speech Communities 019 23 Networks and Repertoires 020 23-24 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- I Sociolinguistic Constraints on language Contact 021 25 Wave Model of Language Contact and Change 022 26 Lesson No. 5 Spatial Diffusion by Gravity 023 27 Access to the Codes 024 27-28 Rigidity of the Social Matrix 025 29-30 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- II Variables and Variants 026 31 Types of Variables and Variants 027 31-32 Lesson No. -

Degree Thesis English (61-90) Credits

Degree Thesis English (61-90) credits Keeping Mum: An Exploration of Contemporary Kinship Terminology in British, American and Swedish Cultures Linguistics, 15 credits Halmstad 2021-06-21 Gerd Bexell HALMSTAD UNIVERSITY Abstract Keeping Mum: An Exploration of Contemporary Kinship Terminology in British, American and Swedish Cultures The aim of this paper is to briefly clarify the categorization and usage of kinship terms in American and British English in comparison with the Swedish kinship terms, both considering the vocative use and the referential function. There will also be a comparison with previous studies. The Swedish language contains considerably more detailed definitions for kinship. By choosing mostly informants with experience of both language cultures, this paper will investigate and explore whether English speakers themselves experience this as a lack of kinship vocabulary, and in what circumstances supplementary explanation is needed to clarify the identities of referents and addressees. It will further be established how and when the use of such terms can give rise to misunderstandings or confusion. Kinship terms will also be considered in connection with the present social and cultural environment. Seemingly, the use of kin terms has changed over recent decades and there appears to be etymological, lexicological and semantic causes for such misunderstandings. This essay research was conducted using interviews in which informants relate their experiences of language changes as well as regional variations with respect to how family members and relatives are addressed or referred to. Kinship terms are insightful and important within the field of genealogy and have implications for diverse disciplines such as law, church history, genetics, anthropology and popular custom. -

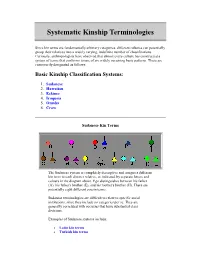

Systematic Kinship Terminologies

Systematic Kinship Terminologies Since kin terms are fundamentally arbitrary categories, different cultures can potentially group their relatives into a widely varying, indefinite number of classifications. Curiously, anthropologists have observed that almost every culture has constructed a system of terms that conforms to one of six widely occurring basic patterns. These are customarily designated as follows: Basic Kinship Classification Systems: 1. Sudanese 2. Hawaiian 3. Eskimo 4. Iroquois 5. Omaha 6. Crow Sudanese Kin Terms The Sudanese system is completely descriptive and assigns a different kin term to each distinct relative, as indicated by separate letters and colours in the diagram above. Ego distinguishes between his father (A), his father's brother (E), and his mother's brother (H). There are potentially eight different cousin terms. Sudanese terminologies are difficult to relate to specific social institutions, since they include no categories per se. They are generally correlated with societies that have substantial class divisions. Examples of Sudanese systems include: Latin kin terms Turkish kin terms Old English kin terms Return to Top Hawaiian Kin Terms The Hawaiian system is the least descriptive and merges many different relatives into a small number of categories. Ego distinguishes between relatives only on the basis of sex and generation. Thus there is no uncle term; (mother's and father's brothers are included in the same category as father). All cousins are classified in the same group as brothers and sisters. Lewis Henry Morgan, a 19th century pioneer in kinship studies, surmised that the Hawaiian system resulted from a situation of unrestricted sexual access or "primitive promiscuity" in which children called all members of their parental generation father and mother because paternity was impossible to acertain. -

Full-Text PDF (Final Published Version)

Racz, P., Passmore, S., & Jordan, F. (2019). Social practice and shared history, not social scale, structure cross-cultural complexity in kinship systems. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/tops.12430 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Wiley at https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Topics in Cognitive Science (2019) 1–22 © 2019 The Authors Topics in Cognitive Science published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of Cognitive Science Society ISSN: 1756-8765 online DOI: 10.1111/tops.12430 This article is part of the topic “The Cultural Evolution of Cognition,” Andrea Bender, Sieghard Beller and Fiona Jordan (Topic Editors). For a full listing of topic papers, see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1756-8765/earlyview Social Practice and Shared History, Not Social Scale, Structure Cross-Cultural Complexity in Kinship Systems Peter Racz,a,b Sam Passmore,b Fiona M. Jordanb aCognitive Development Center, Central European University bEvolution of Cross-Cultural Diversity Lab, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol Received 31 July 2018; received in revised form 10 April 2019; accepted 12 April 2019 Abstract Human populations display remarkable diversity in language and culture, but the variation is not without limit. -

Perspectives: an Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle De González, and Thomas Mcilwraith

Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith 2017 American Anthropological Association American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN: 978–1-931303–55–2 http://www.perspectivesanthro.org This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. Family and Marriage Mary Kay Gilliland, Central Arizona College [email protected] LEARNING OBJECTIVES Family and marriage may at first seem to be famil- • Describe the variety of human iar topics. Families exist in all societies and they are part families cross-culturally with of what makes us human. However, societies around the examples. world demonstrate tremendous variation in cultural under- • Discuss variation in parental rights standings of family and marriage. Ideas about how people and responsibilities. are related to each other, what kind of marriage would be • Distinguish between matrilineal, ideal, when people should have children, who should care patrilineal, and bilateral kinship for children, and many other family related matters differ systems. cross-culturally. While the function of families is to fulfill • Identify the differences between basic human needs such as providing for children, defin- kinship establish by blood and kinship ing parental roles, regulating sexuality, and passing property established by marriage. and knowledge between generations, there are many vari- • Evaluate the differences between ations or patterns of family life that can meet these needs. -

Course No. 102..Sociology of Family, Marriage and Kinship

Directorate of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU JAMMU STUDY MATERIAL For M.A. SOCIOLOGY (SEMESTER-IST) TITLE : SOCIOLOGY OF FAMILY, KINSHIP AND MARRIAGE SESSION 2020 COURSE No. SOC-C-102 LESSON No. 1-20 Course Co-ordinator : Teacher Incharge : PROF. ABHA CHAUHAN DR. NEHA VIJ H.O.D., Deptt. of Sociology P. G. Sociology University of Jammu. University of Jammu. http:/wwwdistanceeducationju.in Printed and Published on behalf of the Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu by the Director, DDE University of Jammu, Jammu. 1 SCRIPT WRITERS * Prof. B.K. Nagla * Prof. Madhu Nagla * Prof. J.R. Panda * Prof. Ashish Saxena * Prof. Abha Chauhan * Prof. Vishav Raksha * Prof. Neeru Sharma * Dr. Hema Gandotra * Dr. Neharica Subhash * Dr. Nisha Sharma * Dr. Kuljeet Singh © Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu 2020 • All rights reserved . No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the DDE , University of Jammu. • The script writer shall be responsible for the lesson/script submitted to the DDE and any plagiarism shall be his / her entire responsibility. Printed by : Sushil Printers /2020/650 2 Syllabus of Sociology M.A. lst Semester To be held in the year Dec. 2019, 2020 & 2021 (Non-CBCS) Course No. SOC-C-102 Title : Sociology of Family, Kinship and Marriage Credits : 6 Max. Marks : 100 Duration of examination : 2 & 1/2 hrs. (a) Semester examination : 80 (b) Sessional assessment : 20 Objectives : To demonstrate to the students the universally acknowledged social importance of Family and Kinship structure and familiarize them with the rich diversity in the types of networks of relationship created by genealogical links of marriage and other social ties. -

Internal Co-Selection and the Coherence of Kinship Typologies

Biological Theory https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-021-00379-6 THEMATIC ISSUE ARTICLE: EVOLUTION OF KINSHIP SYSTEMS Kin Against Kin: Internal Co‑selection and the Coherence of Kinship Typologies Sam Passmore1 · Wolfgang Barth2 · Kyla Quinn2 · Simon J. Greenhill2,3 · Nicholas Evans2 · Fiona M. Jordan1 Received: 4 December 2020 / Accepted: 12 April 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Across the world people in diferent societies structure their family relationships in many diferent ways. These relationships become encoded in their languages as kinship terminology, a word set that maps variably onto a vast genealogical grid of kinship categories, each of which could in principle vary independently. But the observed diversity of kinship terminology is considerably smaller than the enormous theoretical design space. For the past century anthropologists have captured this variation in typological schemes with only a small number of model system types. Whether those types exhibit the internal co-selection of parts implicit in their use is an outstanding question, as is the sufciency of typologies in capturing variation as a whole. We interrogate the coherence of classic kinship typologies using modern statistical approaches and systematic data from a new database, Kinbank. We frst survey the canonical types and their assumed patterns of internal and external co-selection, then present two data-driven approaches to assess internal coherence. Our frst analysis reveals that across parents’ and ego’s (one’s own) generation, typology has limited predictive value: knowing the system in one generation does not reliably predict the other. Though we detect limited co-selection between generations, “disharmonic” systems are equally common. -

Developments in Polynesian Ethnology

Developments in Polynesian Ethnology Developments in Polynesian Ethnology Edited by Alan Howard and Robert Borofsky Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824881962 (PDF) 9780824881955 (EPUB) This version created: 20 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. ©1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved For Jan and Nancy CONTENTS Title Page ii Copyright 3 Dedication iv Acknowledgments vi 1. Introduction ALAN HOWARD AND ROBERT BOROFSKY 1 2. Prehistory PATRICK V. KIRCH 14 3. Social Organization ALAN HOWARD AND JOHN KIRKPATRICK 52 4. Socialization and Character Development JANE RITCHIE AND JAMES RITCHIE 105 5. Mana and Tapu BRADD SHORE 151 6. Chieftainship GEORGE E. MARCUS 187 7. Art and Aesthetics ADRIENNE L. KAEPPLER 224 8. The Early Contact Period ROBERT BOROFSKY AND ALAN HOWARD 257 9. Looking Ahead ROBERT BOROFSKY AND ALAN HOWARD 290 Bibliography 307 Contributors 407 Notes 410 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A VARIETY of people contributed to the preparation of this book. -

IE Kinship Terms As an Interdisciplinary Topic Reconstruction of Social Realities –Anthropological Views and Methodological Considerations1

IE kinship terms as an interdisciplinary topic Reconstruction of social realities –anthropological views and methodological considerations1 Veronika Milanova University of Vienna ([email protected]) Draft. Not for quotations! In the recent years I’ve become more anthropologically- oriented. And I’ve tried to squeeze out of these Sumerian literary texts whatever they can reveal about the Sumerian society and about the Sumerian culture, in general, and psychological aspects of the Sumerian culture. Unfortunately for me or perhaps fortunately, in some respect, the authors of the Sumerian literary documents were not scholarly-oriented sociologists. They were visionary poets and emotional bards. So whatever you want to learn about the society, you have to read between the lines and work inferentially and indirectly. S.N. Kramer. The Sumerian woman (talk, Chicago, Oct., 16 1975)2 1 I would like to express my gratitude to the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) for financing my PhD project (Doc-Stipendium) and my thesis adviser Melanie Malzahn for facilitating my harmonic academic advance and providing me with the right proportion of control and freedom. I am also greatly indebted to the anthropologists who have counselled me or simply discussed topics of Kinship Studies with me: Wolfgang Kraus (University of Vienna), Robert Parkin (Oxford University), Vladimir A. Popov (Kunstkammer, St. Petersburg), Patrick Heady (Max Plank Institute for Social Anthropology) and Akira Takada (Kyoto University). And last but not least, I am grateful to the assyriologist Michael Jursa (University of Vienna), who also has a high competence in sociological and anthropological questions, for the final expertise of this paper. -

Kinship Practices, Kinship Systems (As Normative Structures) Can Be Organized According to a More Limited Set of Rules, Categories, and Possible Arrangements

Anthropology 1 • The principle of organizing individuals into social groups, roles, and categories based on parentage and marriage. • Ensures continuity and learning between generations • Involves the care and survival of children • Provides for the orderly transmission of property and social possessions • systematic means of inheritance and succession • Defines the universe of people that can be counted on for aid • Determines • economic and social relationships between members of a kin group • structures of sentiment 1 • Although cultures show enormous variability in kinship practices, kinship systems (as normative structures) can be organized according to a more limited set of rules, categories, and possible arrangements. • Membership in a kinship group is not voluntary. • It is determined by the rules of kinship in that culture. • CONSANGUINEAL • related biologically, by ‘blood’ • the primary focus of this type of relationship is on parent/child affiliation • AFFINAL • related by marriage, contract or law • custom or common law • this relationship focuses primarily on spousal relationships and the creation of new family bonds. • FICTIVE • kinship that is recognized in absence of blood or marriage. • Who you can marry? • Who you cannot? • Who decides? Who will choose your marriage partner? 2 3 • A human universal • Forbids sexual relations between certain categories of close relations • No sex equates as well to no marriage 4 • Endogamy • must marry within your group • Religion • Caste • Class • Race • Ethnicity • etc. • Exogamy • must -

GIPE-001784-Contents.Pdf

PRIMITIVE SOCIET'Y BY ROBERT H. LOWIE, PH.D. ASSOCIATE CURATOR, ANTHROPOLOGY, AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY. AUTHOR OP CuUUTt and Ethnoloyu. LoNDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS, LTD., BROADWAY HousB. 68-74. CARTER LAMB; E.C. 1921 Printed io Great BritaiD by MACKAY II; Co., LTD, CHATHAM. PREFACE NTHROPOLOGISTS are hard put to It when asked to A recommend a book that shall give the layman a brief .umrr.ary of what iB now known regarding their Bcience as a whole or anyone of its branches. They are usually obliged to ronfcss that such an up-to-date synthesis ~s is likely to satisfy the questioner does not exist. In no department of anthropology hus the wallt of a modern summary made itself more painfully felt than in that of social organization. Sociologists, historians, and students of comparative I u risprudence all require the data the unthropologist might supply, but for lack of a general guide they have been content to Hnd inspiration in Morgan's Ancient Sotiety, a book written when scientiflc ethnography was in its infuncy. Since 1877 anthropologists have not merely amassed a wealth of concrete material but have developed new methods and points of view thut render Morgan hopelessly antiquated. His work remains an important pioneer elTort by a man of estimable Intelligence and exemplary industry, but to get one's knowledge of primitive society therefrom nowadays is like getting one's biology from some pre-Darwinian naturalist. It is em phlltico\ly a book for the historian of anthropology and not for the goneral reader. As I discovered during a year's lerturing at the Vniversity of COliforni", Ule college student who takes anthropological courses "ulTors o.s grievollslYfrom the want of an introductory statement on primitive social organization as the interested layman or the investigator of neighboring branches of knowledge. -

Kinship, Marriage and Family

Kebede Lemu Bekelcha, Aregash Eticha Sefera., GJAH, 2019 2:12 Review Article GJAH (2019) 2:12 Global Journal of Arts and Humanities (ISSN:2637-4765) Kinship, Marriage and Family Kebede Lemu Bekelcha1, Aregash Eticha Sefera2 Department of Social Anthropology, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Bule Hora University Introduction This paper focuses mainly on marriage, family and kinship. An- *Correspondence to Author: thropologists traditionally have a strong interest in families, along Kebede Lemu Bekelcha with larger systems of kinship and marriage. These terms are core in anthropology discipline. They are socially constructed Department of Social Anthropology, and have different meanings across culture. All these three con- Faculty of Social Sciences and Hu- cepts are discussed in this paper accordingly with necessary ex- manities, Bule Hora University amples. How to cite this article: Kebede Lemu Bekelcha, Aregash Eticha Sefera. Kinship, Marriage and Family . Global Journal of Arts and Humanities, 2019, 2:12 eSciPub LLC, Houston, TX USA. Website: https://escipub.com/ GJAH:https://escipub.com/global-journal-of-arts-and-humanities// 1 Kebede Lemu Bekelcha, Aregash Eticha Sefera., GJAH, 2019 2:12 Kinship relatives—people related by birth. Affines are “in-laws”—people related by marriage. Among Studies of kinship and households have long your consanguineous relatives are your been a hallmark of sociocultural anthropology. parents, siblings, grandparents, parents’ When people form an organized, cooperative siblings, and cousins. Your affines include your group based on their kinship relationships, sister’s husband, wife’s mother, and father’s anthropologists call it a kin group (Peoples and sister’s husband. In many societies, people Bailey, 2012:165).