Order and the Literary Rendering of Chaos: Children’S Literature As Knowledge, Culture, and Social Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Legibility: Practice/Prospect in Contemporary Anthropology”

Fall 2018, Volume 59 No. 3 ~ Call for Papers ~ SWAA 2019 Annual Conference, April 19-20, 2019 in Garden Grove, CA “Legibility: Practice/Prospect in Contemporary Anthropology” President’s Message The concept of legibility is not new to anthropology. Scholars have understood it as a project of high modernism – a project of making state-subjects legible and thus decipherable and easy to manage (Scott 1998). Other scholars have explored the concept in terms of the legibility of state bureaucracies (Das and Poole 2004) or the “legibility effect” of governance that classifies and regulates collectives of people (Trouillot 2001). The 2019 SWAA Annual Conference takes on the task of expanding and thinking through legibility with original and critical anthropological and anthropology-allied research. It also expands upon the concept of legibility to address the prospects that exists within it. Inspired by a recent call for “ethnography attuned to its times” (Fortun 2012) and the possibilities that exist in and through collaborative relationships (See Hamdy and Nye 2016), this conference speaks to the moment we are living in now. If legibility is about decipherability and clarity, how do we make our research legible through scholarly production and pedagogies? How do we make our discipline legible to a broader public through collaboration and other means? This conference seeks to think through legibility as a concept to help us better understand what it means to decipher and make something legible be it communities, individuals, multi- species relationships, economic processes, an archaeological site, evolutionary history, the human genome, our primate relatives, or the archaeological record. -

15-Minute-Break-Catalogue Part-II

Research exhibition on labor Выставка-исследование and leisure in two parts о труде и отдыхе в двух частях October 9—November 15, 2020 9 октября — 15 ноября 2020 Part 2 Часть 2 Дорогие друзья! Мы очень рады, что при поддержке Фонда президентских грантов, междисциплинарного центра Research Arts и галереи «Триумф» нам удалось реализовать в стенах музея вторую часть выставочного проекта «Перерыв 15 минут». Если первая часть была посвящена труду и его изменению в современном мире, то во второй рассматривается время, исключенное из труда. Через инсталляции, видео, аудио, живопись, графику, современную скульптуру и фотографию художники обращаются ко времени активного отдыха и восстановления сил, времени ожидания и лени, времени погружения в собственные размышления и созерцательности. Выставку дополнили экспонаты из собрания Всероссийского музея декоративного искусства — предметы и композиции из кости и дерева, металла и камня, стекла, керамики и ткани, авторы которых в разные эпохи обращались к иллюстрированию всевозможных способов отдохнуть. Елена Титова Директор Всероссийского музея декоративного искусства Dear Friends! We are delighted that, with support of the Presidential Grants for Civil Society Development Foundation, Research Arts Interdisciplinary Center and Triumph Gallery, we are now able to present the second part of 15 Minute Break, hosted by our museum. Whereas the first part addressed labor and the changes it undergoes in the modern world, the second installment examines the time exempted from labor. The artists’ installations, video, audio, paintings, drawings, contemporary sculpture and photography contemplate the time of active leisure and replenishment of energy, Владимир Филатов the time of idle anticipation and laziness, the time of immersion Блюдо «Море» 1967 into own thoughts and contemplation. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Sociolinguistics (ENG510)

Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Sociolinguistics (ENG510) ___________________________________________________________________________________ ©Copyright Virtual University of Pakistan 1 Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Table of Contents Lesson No. Lesson Title Topics Pg. No. INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLINGUISTICS What is Sociolinguistics? 001 8-9 Some Definitions of Sociolinguistics 002 9 Lesson No. 1 Sociolinguistics and Linguistics 003 9-10 Sociolinguistics and the Sociology of Language 004 10 Sociolinguistics and Other Disciplines 005 10-11 SOCIOLINGUISTIC PHENOMENA Sociolinguistic Phenomena and an Imaginary World 006 12-13 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real but Exotic World 007 13-14 Lesson No. 2 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real and Familiar World 008 15 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and We 009 15-16 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and the Changing World 010 16 SOCIOLINGUISTICS AND VARIETIES OF LANGUAGE The Question of Varieties of Language in Sociolinguistics 011 17-18 Lesson No. 3 What Are Linguistics Items? 012 18 The Terms- Variety and Lect 013 18 Types and Significance of Varieties of Language 014 19 Attitude towards Language Varieties 015 19 SPEECH COMMUNITIES What Are Speech Communities? 016 20 Some Definitions of Speech Communities 017 21 Lesson No. 4 Intersecting Communities 018 21-22 Rejecting the Idea of Speech Communities 019 23 Networks and Repertoires 020 23-24 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- I Sociolinguistic Constraints on language Contact 021 25 Wave Model of Language Contact and Change 022 26 Lesson No. 5 Spatial Diffusion by Gravity 023 27 Access to the Codes 024 27-28 Rigidity of the Social Matrix 025 29-30 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- II Variables and Variants 026 31 Types of Variables and Variants 027 31-32 Lesson No. -

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

Degree Thesis English (61-90) Credits

Degree Thesis English (61-90) credits Keeping Mum: An Exploration of Contemporary Kinship Terminology in British, American and Swedish Cultures Linguistics, 15 credits Halmstad 2021-06-21 Gerd Bexell HALMSTAD UNIVERSITY Abstract Keeping Mum: An Exploration of Contemporary Kinship Terminology in British, American and Swedish Cultures The aim of this paper is to briefly clarify the categorization and usage of kinship terms in American and British English in comparison with the Swedish kinship terms, both considering the vocative use and the referential function. There will also be a comparison with previous studies. The Swedish language contains considerably more detailed definitions for kinship. By choosing mostly informants with experience of both language cultures, this paper will investigate and explore whether English speakers themselves experience this as a lack of kinship vocabulary, and in what circumstances supplementary explanation is needed to clarify the identities of referents and addressees. It will further be established how and when the use of such terms can give rise to misunderstandings or confusion. Kinship terms will also be considered in connection with the present social and cultural environment. Seemingly, the use of kin terms has changed over recent decades and there appears to be etymological, lexicological and semantic causes for such misunderstandings. This essay research was conducted using interviews in which informants relate their experiences of language changes as well as regional variations with respect to how family members and relatives are addressed or referred to. Kinship terms are insightful and important within the field of genealogy and have implications for diverse disciplines such as law, church history, genetics, anthropology and popular custom. -

Interview with Layla Abdelrahim Conducted by Bellamy

AbdelRahim, Layla Backwoods journal #2; 2018 1 The Storyteller Who Ate the World: Interview with Layla AbdelRahim conducted by Bellamy Fitzpatrick for Backwoods journal Summer, 2018 http://layla.miltsov.org/ https://www.routledge.com/authors/i10144-layla-abdelrahim In this interview, Layla AbdelRahim expands on the analysis of the predatory and parasitic foundation of civilized economies. She explains how narratives, whether fictional or scientific, encode templates for socio-economic praxis and clarifies the concept of rewilding that she develops in her books Children’s Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation (Routledge 2015; 2018) and Wild Children – Domesticated Dreams: Civilization and the Birth of Education (Fernwood 2013). Bellamy Fitzpatrick Question 1. One of the main themes of your writing is that the stories we tell ourselves, and perhaps more importantly our children, are of the highest importance, that they shape the ways we think and view the world on levels we don’t even notice because they are so normalized to us. Can you talk a bit about how you became interested in this topic with your radical analysis, and then further on how you see civilized stories as crucially different from indigenous ones? Layla AbdelRahim Answer 1. Storytelling in general, and especially recorded stories, provide an efficient mechanism for the transmission of cultural choices. After all, even in oral traditions, stories have proven to be effective in recording past experiences, which they transmit along with warnings, instructions, and prohibitions. Thus, stories can serve as an ethnographic or historical record and concomitantly influence our actions. I became aware of the insidious power of stories when I was working in journalism in the late 1980s. -

![Bright (2017) Screenplay by Max Landis [Shooting Draft 02.29.2016]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9123/bright-2017-screenplay-by-max-landis-shooting-draft-02-29-2016-1729123.webp)

Bright (2017) Screenplay by Max Landis [Shooting Draft 02.29.2016]

BRIGHT Written by Max Landis 12/28/15 Current Revisions by David Ayer 02/29/16 red and blue lights flash in the dark rushing down streets you recognize a glimpse of magic, just a spark the monsters are familiar but the castles are amiss you've been here before but not quite like this For JRR Tolkien and David Ayer, who bring worlds to life. INT. WARD’S HOUSE - BEDROOM - DAY SCOTT WARD can’t sleep. He scowls in defiance at the golden midday sun scorching through the blinds. Plain but handsome, with an ‘I’m in charge here’ buzzcut. A thoughtful man, but no genius, he’s stymied by the daylight. We note the ANGRY BRUISING on his 200-pushups-a-day chest. Ward tries to fall back asleep. No dice. He shifts his weight and peels his Glock off his sweaty back. Sighs and starts counting the cracks in his bedroom ceiling... SMASH TO: EXT. LIQUOR STORE - WARD’S FLASHBACK - DAY A GANGBANGER in a black hoodie bursts out the door with a shotgun! WARD stands there in LAPD uniform. Reaches for his holster -- Breaks leather. Steps into a textbook shooting stance. Muzzle coming on target. Too Late... The GANGBANGER spins aims fires -- KABOOM! INT. WARD’S HOUSE - BEDROOM - DAY Ward gasps awake. His fingertips skim the ugly green and purple bruises on his chest. I’m still alive... INT. WARD’S HOUSE - KITCHEN - DAY Ward shuffles into the kitchen -- Sees SHERRI, his age, inspecting dishes in the sink, looking for the easiest one to wash. Pretty in a champagne room kind of way. -

Beyond the Symbolic and Towards the Collapse

Beyond the Symbolic and towards the Collapse Layla AbdelRahim 2008 Contents 1. Beyond the Symbolic ........................... 3 2. The Collapse ................................ 7 2 1. Beyond the Symbolic John Zerzan is one of the most interesting contemporary thinkers in the United States, at least. Like everything else in life, in order to fully appreciate Zerzan’s contribution to epistemology or the philosophy of civilization, first, one has to read his work and hear his conferences — for, here, I only present my personal interpretation of his theory — and second, consider the context through which his voice and energy resonate. His contribution becomes even more impressive in light of the processes of Western institutionalization of Thought and commodification of Knowledge — a totalitarian context that tolerates no challenge (philosophical or otherwise) that would threaten “the American way of life”. The notion that there is an “American way of life” is not new. It appears withthe colonization and the extermination of aboriginal cultures and life in the Americas. Already in the 17th century, American writers and politicians used the expression to designate their justification for killing and de-territorializing the native human and non-human populations because the colonialists believed in their “inalienable” right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” at the expense of forced labor and other people’s life, liberty and pursuit of happiness — a stance fully revealed with slavery, feudalism and now with underpaid, forced wage-labor in the sup- posedly “post”-industrial economy. Zerzan traces the roots of this cultural system to the logic and practice of domestication and agriculture, i.e. -

“Anarchists Are More Animal Than Human”: Rationality, Savagery, and the Violence of Property

“Anarchists Are More Animal than Human”: Rationality, Savagery, and the Violence of Property Benjamin Abbott When I first read Chris Hedges’ now infamous denunciation of “Black Bloc anarchists” in the Occupy Wall Street movement, I felt as if I had stepped back in time to the turn of the twentieth century. Hedges’ charges of senseless aggression motivated by primal passions and bent only on universal destruction would fit seamlessly into an 1894 issue of the New York Herald-Tribune or Los Angeles Times. However, as Doreen Massey reminds us, such attempts to assign contemporaries to the past denies how we share space in the world and implies belief in a teleological narrative of progress. Invoking tropes of animality to rhetorically construct political opponents as – to use Chandan Reddy's words – “the enemies of modern political society” remains a key persuasive strategy as well as an enduring technology of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism here in the twenty-first century. Even a cursory look at language of the war on terror and its production of the Islamic terrorist as national bête noire demonstrates this. Though I would like to simply dismiss Hedges’ anti-anarchist piece as an anomalous echo of discredited reactionary hyperbole, I instead interpret it as representative of a thriving modern phenomenon. The Occupy Wall Street movement has prompted a proliferation and reemphasis of the preexisting discourse of anarchists as the inhuman and unreasonably violent enemies of humanity.1 This essay takes the Hedges article as a point of departure to explore earlier expressions of this discourse specifically through the lens of property. -

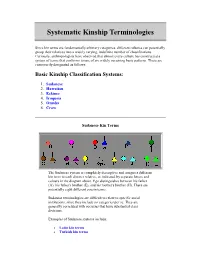

Systematic Kinship Terminologies

Systematic Kinship Terminologies Since kin terms are fundamentally arbitrary categories, different cultures can potentially group their relatives into a widely varying, indefinite number of classifications. Curiously, anthropologists have observed that almost every culture has constructed a system of terms that conforms to one of six widely occurring basic patterns. These are customarily designated as follows: Basic Kinship Classification Systems: 1. Sudanese 2. Hawaiian 3. Eskimo 4. Iroquois 5. Omaha 6. Crow Sudanese Kin Terms The Sudanese system is completely descriptive and assigns a different kin term to each distinct relative, as indicated by separate letters and colours in the diagram above. Ego distinguishes between his father (A), his father's brother (E), and his mother's brother (H). There are potentially eight different cousin terms. Sudanese terminologies are difficult to relate to specific social institutions, since they include no categories per se. They are generally correlated with societies that have substantial class divisions. Examples of Sudanese systems include: Latin kin terms Turkish kin terms Old English kin terms Return to Top Hawaiian Kin Terms The Hawaiian system is the least descriptive and merges many different relatives into a small number of categories. Ego distinguishes between relatives only on the basis of sex and generation. Thus there is no uncle term; (mother's and father's brothers are included in the same category as father). All cousins are classified in the same group as brothers and sisters. Lewis Henry Morgan, a 19th century pioneer in kinship studies, surmised that the Hawaiian system resulted from a situation of unrestricted sexual access or "primitive promiscuity" in which children called all members of their parental generation father and mother because paternity was impossible to acertain. -

Full-Text PDF (Final Published Version)

Racz, P., Passmore, S., & Jordan, F. (2019). Social practice and shared history, not social scale, structure cross-cultural complexity in kinship systems. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/tops.12430 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Wiley at https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Topics in Cognitive Science (2019) 1–22 © 2019 The Authors Topics in Cognitive Science published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of Cognitive Science Society ISSN: 1756-8765 online DOI: 10.1111/tops.12430 This article is part of the topic “The Cultural Evolution of Cognition,” Andrea Bender, Sieghard Beller and Fiona Jordan (Topic Editors). For a full listing of topic papers, see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1756-8765/earlyview Social Practice and Shared History, Not Social Scale, Structure Cross-Cultural Complexity in Kinship Systems Peter Racz,a,b Sam Passmore,b Fiona M. Jordanb aCognitive Development Center, Central European University bEvolution of Cross-Cultural Diversity Lab, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol Received 31 July 2018; received in revised form 10 April 2019; accepted 12 April 2019 Abstract Human populations display remarkable diversity in language and culture, but the variation is not without limit.