Degree Thesis English (61-90) Credits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Familial Generations Tutorial

UCLA Mathematical Anthropology and Cultural Theory Title FAMILIAL GENERATIONS TUTORIAL Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5m51s6k6 Author Denham, Woodrow W Publication Date 2011-09-15 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: SERIES: MACT LECTURE NOTES AND WORKING PAPERS FAMILIAL GENERATIONS TUTORIAL VERSION 1.0, SEPTEMBER 15, 2011 WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D. RETIRED INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: SERIES: LECTURE NOTES AND WORKING PAPERS ISSN 1544-5879 DENHAM: FAMILIAL GENERATIONS TUTORIAL WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: SERIES: MACT LECTURE NOTES AND WORKING PAPERS FAMILIAL GENERATIONS TUTORIAL WOODROW W. DENHAM Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Disambiguation ........................................................................................................................... 3 Basics .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Generations and kin types ..................................................................................................4 Descent generations ...........................................................................................................6 -

Popov Proof.Pages

THE STUDY OF KINSHIP SYSTEMS AND TERMINOLOGIES IN RUSSIA AND THE SOVIET UNION A SHORT HISTORY AND THE CURRENT STATE OF A DISCIPLINE AT THE INTERSECTION OF ETHNOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY Popov, Vladimir A. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology Russian Academy of Sciences St. Petersburg RUSSIA Dziebel, German V. GSW Worldwide New York, New York USA The paper traces the origin of kinship studies as a subdiscipline of ethnography in Russia and the former Soviet Union. It identifies three long-term trends in the study of kinship (typological, ethnosociological and ethnocultural) in the region and highlights the importance of evolutionary thinking and the conceptual distinction between content and manifestation in the study of kin terminological systems. It presents several illustrative studies that demonstrate how Russian and Soviet scholars have tackled these trends and conceptual principles in practice. Teaching or writing a historiography of the pre-Soviet, Soviet and post-Soviet Russian and East European social sciences to a Western audience is a challenging task. A diverse set of barriers – linguistic, cultural and political – have compounded over generations to produce a situation where influential Russian thinkers from the remote and recent past (such as the evolutionary biologist Kropotkin or the ethnologist and geographer Gumilev) are virtually unknown in the West because of the perceived (importantly, sometimes in Russia, sometimes in the West) density, foreigness or political bias of their ideas; others (such as Potebnia, Veselovsky, Bakhtin, Lotman, Chayanov, Vygotsky, and Shklovsky) get belatedly recognized in the West due to the valiant efforts of some English-speaking academics, but they still remain poorly integrated into general Western curricula. -

Sociolinguistics (ENG510)

Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Sociolinguistics (ENG510) ___________________________________________________________________________________ ©Copyright Virtual University of Pakistan 1 Sociolinguistics-ENG510 VU Table of Contents Lesson No. Lesson Title Topics Pg. No. INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLINGUISTICS What is Sociolinguistics? 001 8-9 Some Definitions of Sociolinguistics 002 9 Lesson No. 1 Sociolinguistics and Linguistics 003 9-10 Sociolinguistics and the Sociology of Language 004 10 Sociolinguistics and Other Disciplines 005 10-11 SOCIOLINGUISTIC PHENOMENA Sociolinguistic Phenomena and an Imaginary World 006 12-13 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real but Exotic World 007 13-14 Lesson No. 2 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and a Real and Familiar World 008 15 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and We 009 15-16 Sociolinguistic Phenomena and the Changing World 010 16 SOCIOLINGUISTICS AND VARIETIES OF LANGUAGE The Question of Varieties of Language in Sociolinguistics 011 17-18 Lesson No. 3 What Are Linguistics Items? 012 18 The Terms- Variety and Lect 013 18 Types and Significance of Varieties of Language 014 19 Attitude towards Language Varieties 015 19 SPEECH COMMUNITIES What Are Speech Communities? 016 20 Some Definitions of Speech Communities 017 21 Lesson No. 4 Intersecting Communities 018 21-22 Rejecting the Idea of Speech Communities 019 23 Networks and Repertoires 020 23-24 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- I Sociolinguistic Constraints on language Contact 021 25 Wave Model of Language Contact and Change 022 26 Lesson No. 5 Spatial Diffusion by Gravity 023 27 Access to the Codes 024 27-28 Rigidity of the Social Matrix 025 29-30 LANGUAGE CONTACT AND VARIATION- II Variables and Variants 026 31 Types of Variables and Variants 027 31-32 Lesson No. -

Publications Were Issued in Latin Or German

August 23–28, 2016 St. Petersburg, Russia EACS 2016 21st Biennial Conference of the European Association for Chinese Studies Book of ABStractS 2016 EACS- The European Association for Chinese Studies The European Association for Chinese Studies (EACS) is an international organization representing China scholars from all over Europe. Currently it has more than 700 members. It was founded in 1975 and is registered in Paris. It is a non-profit orga- nization not engaging in any political activity. The purpose of the Association is to promote and foster, by every possible means, scholarly activities related to Chinese Studies in Europe. The EACS serves not only as the scholarly rep- resentative of Chinese Studies in Europe but also as contact or- ganization for academic matters in this field. One of the Association’s major activities are the biennial con- ferences hosted by various centres of Chinese Studies in diffe- rent European countries. The papers presented at these confer- ences comprise all fields from traditional Sinology to studies of modern China. In addition, summer schools and workshops are organized under the auspices of the EACS. The Association car- ries out scholarly projects on an irregular basis. Since 1995 the EACS has provided Library Travel Grants to support short visits for research in major sinological libraries in Western Europe. The scheme is funded by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation and destined for PhD students and young scholars, primarily from Eastern European countries. The EACS furthers the careers of young scholars by awarding a Young Scholar Award for outstanding research. A jury selects the best three of the submitted papers, which are then presented at the next bi-an- nual conference. -

Kinship Terminology from a Cultural Perspective: Japanese Versus? Hungarian

日本語とジェンダー 第14号(2014) 【研究例会 IN ハンガリー 発表】 Kinship Terminology from a Cultural Perspective: Japanese versus? Hungarian Judit Hidasi This article is part of a longer study in progress on the relationship of language use and society with regards to kinship terminology. The article first gives some frame to the study by briefly introducing the concept of kinship, next different descent patterns in societies to be followed by categorization patterns of kinship terminology (Morgan) in Hungarian and Japanese. It is assumed that kin terms are valuable clues to the nature of a kinship system in a society as well as to the social statuses and roles of kinsmen, of the roles of men and women. Changes in kinship terminology also reflect to a certain extent changes of a given society. What is kinship? Kinship refers to the culturally defined relationships between individuals who are commonly thought of as having family ties. All societies use kinship as a basis for forming social groups and for classifying people. However, there is a great amount of variability in kinship rules and patterns around the world. In order to understand social interaction, attitudes, and motivations in most societies, it is essential to know how their kinship systems function. In many societies, kinship is the most important social organizing principle along with gender and age. Kinship also provides a means for transmitting status and property from generation to generation. It is not a mere coincidence that inheritance rights usually are based on the closeness of kinship links. Kinship connections are based on two categories of bonds: those created by marriage (affinal relatives: husband, wife, mother-in-law, father-in-law, brother-in-law, sister-in-law) and those that result from descent (consanguinal that is ’blood’ relatives: mother, father, grandparents, children, grandchildren, uncles, aunts and cousins), which is a socially recognized link between ancestors and descendants. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

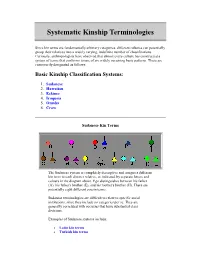

Systematic Kinship Terminologies

Systematic Kinship Terminologies Since kin terms are fundamentally arbitrary categories, different cultures can potentially group their relatives into a widely varying, indefinite number of classifications. Curiously, anthropologists have observed that almost every culture has constructed a system of terms that conforms to one of six widely occurring basic patterns. These are customarily designated as follows: Basic Kinship Classification Systems: 1. Sudanese 2. Hawaiian 3. Eskimo 4. Iroquois 5. Omaha 6. Crow Sudanese Kin Terms The Sudanese system is completely descriptive and assigns a different kin term to each distinct relative, as indicated by separate letters and colours in the diagram above. Ego distinguishes between his father (A), his father's brother (E), and his mother's brother (H). There are potentially eight different cousin terms. Sudanese terminologies are difficult to relate to specific social institutions, since they include no categories per se. They are generally correlated with societies that have substantial class divisions. Examples of Sudanese systems include: Latin kin terms Turkish kin terms Old English kin terms Return to Top Hawaiian Kin Terms The Hawaiian system is the least descriptive and merges many different relatives into a small number of categories. Ego distinguishes between relatives only on the basis of sex and generation. Thus there is no uncle term; (mother's and father's brothers are included in the same category as father). All cousins are classified in the same group as brothers and sisters. Lewis Henry Morgan, a 19th century pioneer in kinship studies, surmised that the Hawaiian system resulted from a situation of unrestricted sexual access or "primitive promiscuity" in which children called all members of their parental generation father and mother because paternity was impossible to acertain. -

Kinship and Descent

Please read: A personal appeal from Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales [[Hide]] [[Show]] Wikipedia Forever Our shared knowledge. Our shared treasure. Help us protect it. [[Show]] Wikipedia Forever Our shared knowledge. Our shared treasure. Help us protect it. Kinship From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation,, search For other uses, see Kinship (disambiguation).. Close relationships Types of relationships Boyfriend ·· Bromance ·· Casual ·· Cicisbeo ·· Cohabitation ·· Concubinage ·· Courtesan ·· Domestic partnership ·· Family ·· Friendship ·· Girlfriend ·· Husband ·· Kinship ·· Marriage ·· Mistress (lover) ·· Monogamy ·· Non- monogamy ·· Pederasty ·· Polyamory ·· Polyfidelity ·· Polygamy ·· Romantic friendship ·· Same-sex relationship ·· Significant other ·· Soulmate ·· Widowhood ·· Wife Major relationship events Mating ·· Courtship ·· Bonding ·· Divorce ·· Infidelity ·· Relationship breakup ·· Romance ·· Separation ·· Wedding Feelings and emotions Affinity ·· Attachment ·· Compersion ·· Intimacy ·· Jealousy ·· Limerence ·· Love ·· Passion ·· Platonic love ·· Polyamory ·· Psychology of sexual monogamy Human practices Bride price ((Dower ·· Dowry)) ·· Hypergamy ·· Infidelity ·· Sexuality Relationship abuse Child abuse ·· Elder abuse ·· Infidelity ·· Spousal abuse ·· Teen dating violence v •• d •• e Kinship is a relationship between any entities that share a genealogical origin, through either biological, cultural, or historical descent. In anthropology the kinship system includes people related both by descent and marriage, while -

Full-Text PDF (Final Published Version)

Racz, P., Passmore, S., & Jordan, F. (2019). Social practice and shared history, not social scale, structure cross-cultural complexity in kinship systems. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/tops.12430 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Wiley at https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12430 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Topics in Cognitive Science (2019) 1–22 © 2019 The Authors Topics in Cognitive Science published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of Cognitive Science Society ISSN: 1756-8765 online DOI: 10.1111/tops.12430 This article is part of the topic “The Cultural Evolution of Cognition,” Andrea Bender, Sieghard Beller and Fiona Jordan (Topic Editors). For a full listing of topic papers, see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1756-8765/earlyview Social Practice and Shared History, Not Social Scale, Structure Cross-Cultural Complexity in Kinship Systems Peter Racz,a,b Sam Passmore,b Fiona M. Jordanb aCognitive Development Center, Central European University bEvolution of Cross-Cultural Diversity Lab, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol Received 31 July 2018; received in revised form 10 April 2019; accepted 12 April 2019 Abstract Human populations display remarkable diversity in language and culture, but the variation is not without limit. -

Perspectives: an Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle De González, and Thomas Mcilwraith

Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith 2017 American Anthropological Association American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN: 978–1-931303–55–2 http://www.perspectivesanthro.org This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. Family and Marriage Mary Kay Gilliland, Central Arizona College [email protected] LEARNING OBJECTIVES Family and marriage may at first seem to be famil- • Describe the variety of human iar topics. Families exist in all societies and they are part families cross-culturally with of what makes us human. However, societies around the examples. world demonstrate tremendous variation in cultural under- • Discuss variation in parental rights standings of family and marriage. Ideas about how people and responsibilities. are related to each other, what kind of marriage would be • Distinguish between matrilineal, ideal, when people should have children, who should care patrilineal, and bilateral kinship for children, and many other family related matters differ systems. cross-culturally. While the function of families is to fulfill • Identify the differences between basic human needs such as providing for children, defin- kinship establish by blood and kinship ing parental roles, regulating sexuality, and passing property established by marriage. and knowledge between generations, there are many vari- • Evaluate the differences between ations or patterns of family life that can meet these needs. -

Course No. 102..Sociology of Family, Marriage and Kinship

Directorate of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU JAMMU STUDY MATERIAL For M.A. SOCIOLOGY (SEMESTER-IST) TITLE : SOCIOLOGY OF FAMILY, KINSHIP AND MARRIAGE SESSION 2020 COURSE No. SOC-C-102 LESSON No. 1-20 Course Co-ordinator : Teacher Incharge : PROF. ABHA CHAUHAN DR. NEHA VIJ H.O.D., Deptt. of Sociology P. G. Sociology University of Jammu. University of Jammu. http:/wwwdistanceeducationju.in Printed and Published on behalf of the Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu by the Director, DDE University of Jammu, Jammu. 1 SCRIPT WRITERS * Prof. B.K. Nagla * Prof. Madhu Nagla * Prof. J.R. Panda * Prof. Ashish Saxena * Prof. Abha Chauhan * Prof. Vishav Raksha * Prof. Neeru Sharma * Dr. Hema Gandotra * Dr. Neharica Subhash * Dr. Nisha Sharma * Dr. Kuljeet Singh © Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu 2020 • All rights reserved . No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the DDE , University of Jammu. • The script writer shall be responsible for the lesson/script submitted to the DDE and any plagiarism shall be his / her entire responsibility. Printed by : Sushil Printers /2020/650 2 Syllabus of Sociology M.A. lst Semester To be held in the year Dec. 2019, 2020 & 2021 (Non-CBCS) Course No. SOC-C-102 Title : Sociology of Family, Kinship and Marriage Credits : 6 Max. Marks : 100 Duration of examination : 2 & 1/2 hrs. (a) Semester examination : 80 (b) Sessional assessment : 20 Objectives : To demonstrate to the students the universally acknowledged social importance of Family and Kinship structure and familiarize them with the rich diversity in the types of networks of relationship created by genealogical links of marriage and other social ties. -

Componential Analysis of Kin Terms ― Some Problems and Their Solutions

Vladimir Pericliev 129 Journal of Universal Language 15-1 March 2014, 137-168 1) Componential Analysis of Kin Terms ― Some Problems and their Solutions Vladimir Pericliev Institute of Mathematics and Informatics, Bulgaria Abstract Componential analysis of kinship vocabulary has a long tradition, but a look at the practicing of the method reveals two basic problems. The first pertains to ensuring “consistent” kin term definitions (i.e., definitions with necessary and sufficient components), and the second to the discovery and handling of multiple solutions to kinship systems. The paper introduces a computer program implemented to handle these two problems, and in general, designed to study kinship vocabulary. The program guarantees consistent componential models and the discovery of all alternative models, as well as introduces simplicity constraints to reduce the usually huge number of alternatives to a unique or just a couple of models. We illustrate the problems with examples from the literature and apply the program to a complex kinship vocabulary (Serbo-Croatian) to show its operation. Keywords: componential analysis, kinship terms, the KINSHIP program Vladimir Pericliev Institute of Mathematics and Informatics, bl. 8 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria Phone: (+3592)9792877; Email: [email protected] Received January 24, 2014; Revised February 20, 2014; Accepted February 27, 2014. 130 Componential Analysis of Kin Terms ― Some Problems and their Solutions 1. Introduction The idea of “system” is fundamental in linguistics, and componential analysis is the method for exposing the systems of linguistic entities. In componential analysis, the meaning of the entities forming a system is described as a conjunction of smaller components that are necessary and jointly sufficient to distinguish each entity in the system from all others.