Genotyping by Sequencing Reveals the Interspecific C. Maxima / C. Reticulata Admixture Along the Genomes of Modern Citrus Variet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

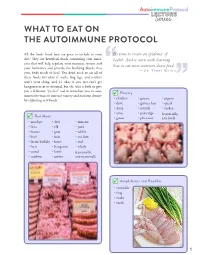

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

An Orangelo Is a Citrus Fruit That Is a Cross Between an Orange and What Other Fruit?

An orangelo is a citrus fruit that is a cross between an orange and what other fruit? Continue This article contains a list of links related to reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it has no in-line links. Please help improve this article by entering more accurate quotes. (May 2015) (Learn how and when to delete this template message) OrangeloHybrid parentageCitrus paradisi × Citrus sinensisOriginPuerto Rico An orangelo (Spanish chironja - C. paradisi × C. sinensis) is a hybrid citrus fruit that is believed to originate in Puerto Rico. The fruit, a cross between grapefruit and orange, spontaneously appeared in the shade of trees grown on coffee plantations in the Puerto Rican Highlands. In 1956, Carlos G. Moscoso of the Horticultural and Agricultural Expansion Service at the University of Puerto Rico noticed trees that grew fruit that were larger and brighter than other trees on plantations. The Rootstock trials led to the development of a hybrid commonly known as chironia. In Puerto Rican Spanish, the name portmanteau is orange (Puerto Rico Spanish: porcelain) and grapefruit (toronja). Orangelos are often eaten in the same way as grapefruit (cut in half and eaten with a grapefruit spoon), but sweeter and brighter in color than grapefruit, and easier to clean. They are round to pear-shaped, with 9-13 segments. References a b Morton, J. (1987). Orange. hort.purdue.edu. received on January 17, 2017. I don't know what to do. fruitsinfo.com. Received on January 17, 2017. Chironja's external references to the Citrus Variety Collection. PUERTO RICAN CHIRONJA - A new type of citrus Chironja on citrus ID Puerto Rico chironja-new all-purpose citrus fruits This article related to fruit is a stub. -

Survey of Phenolic Compounds Produced in Citrus

USDA ??:-Z7 S rveyof Phenolic United States Department of Agriculture C mpounds Produced IliIIiI Agricultural Research In Citrus Service Technical Bulletin Number 1856 December 1998 United States Department of Agriculture Survey of Phenolic Compounds Agricultural Produced in Citrus Research Service Mark Berhow, Brent Tisserat, Katherine Kanes, and Carl Vandercook Technical Bulletin Number 1856 December 1998 This research project was conducted at USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Fruit and Vegetable Chem istry laboratory, Pasadena, California, where Berhow was a research chemist, TIsserat was a research geneticist, Kanes was a research associate, and Vandercook, now retired, was a research chemist. Berhow and Tisserat now work at the USDA-ARS National Center for AgriCUltural Utilization Research, Peoria, Illinois, where Berhow is a research chemist and Tisserat is a research geneticist. Abstract Berhow, M., B. Tisserat, K. Kanes, and C. Vandercook. 1998. Survey of Mention of trade names or companies in this publication is solely for the Phenolic Compounds Produced in Citrus. U.S. Department ofAgriculture, purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommenda Agricultural Research Service, Technical Bulletin No. 1856, 158 pp. tion or endorsement by the U. S. Department ofAgriculture over others not mentioned. A survey of phenolic compounds, especially flavanones and flavone and flavonol compounds, using high pressure liquid chromatography was While supplies last, single copies of this publication may be obtained at no performed in Rutaceae, subfamily Aurantioideae, representing 5 genera, cost from- 35 species, and 114 cultivars. The average number of peaks, or phenolic USDA, ARS, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research compounds, occurring in citrus leaf, flavedo, albedo, and juice vesicles 1815 North University Street were 21, 17, 15, and 9.3, respectively. -

Joimalofagmoiltdraiesea

JOIMALOFAGMOILTDRAIESEARCH VOL. XIX WASHINGTON, D. C, JULY 15, 1920 No. 8 RELATIVE SUSCEPTIBILITY TO CITRUS-CANKER OF DIFFERENT SPECIES AND HYBRIDS OF THE GENUS CITRUS, INCLUDING THE WILD RELATIVES » By GEORGE I*. PELTIER, Plant Pathologist, Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, and Agent, Bureau of Plant Industry, United States Department of Agriculture, and WILLIAM J. FREDERICH, Assistant Pathologist, Bureau of Plant Industry, United States Department of Agriculture 2 INTRODUCTION In a preliminary report (6)3 the senior author briefly described the results obtained under greenhouse conditions for a period of six months on the susceptibility and resistance to citrus-canker of a number of plants including some of the wild relatives, Citrus fruits, and hybrids of the genus Citrus. Since that time the plants reported on have been under close observation; a third experiment has been started, and many inoculations have been made in the isolation field in southern Alabama during the summers of 1917, 1918, and 1919. Many more plants have been successfully inoculated; others have proved to be extremely sus- ceptible; while some of those tested still show considerable resistance. The results obtained up to November 1, 1919, are described in tjhis report. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS In the greenhouse, the methods used and the conditions governing the inoculations described in the preliminary report were closely fol- lowed. The same strain of the organism was used and was applied in the 1 Published with the approval of the Director of the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station. The paper is based upon cooperative investigations between the Office of Crop Physiology and Breeding Investi- gations, Bureau of Plant Industry, United States Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Plant Pathology, Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station. -

Improvement of Subtropical Fruit Crops: Citrus

IMPROVEMENT OF SUBTROPICAL FRUIT CROPS: CITRUS HAMILTON P. ÏRAUB, Senior Iloriiciilturist T. RALPH ROBCNSON, Senior Physiolo- gist Division of Frnil and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Tndusiry MORE than half of the 13 fruit crops known to have been cultivated longer than 4,000 years,according to the researches of DeCandolle (7)\ are tropical and subtropical fruits—mango, oliv^e, fig, date, banana, jujube, and pomegranate. The citrus fruits as a group, the lychee, and the persimmon have been cultivated for thousands of years in the Orient; the avocado and papaya were important food crops in the American Tropics and subtropics long before the discovery of the New World. Other types, such as the pineapple, granadilla, cherimoya, jaboticaba, etc., are of more recent introduction, and some of these have not received the attention of the plant breeder to any appreciable extent. Through the centuries preceding recorded history and up to recent times, progress in the improvement of most subtropical fruits was accomplished by the trial-error method, which is crude and usually expensive if measured by modern standards. With the general accept- ance of the Mendelian principles of heredity—unit characters, domi- nance, and segregation—early in the twentieth century a starting point was provided for the development of a truly modern science of genetics. In this article it is the purpose to consider how subtropical citrus fruit crops have been improved, are now being improved, or are likel3^ to be improved by scientific breeding. Each of the more important crops will be considered more or less in detail. -

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Presentation

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Citrus species & Citrus Relatives Hundreds of varieties available. CITRON Citrus medica • The citron is believed to be one of the original kinds of citrus. • Trees are small and shrubby with an open growth habit. The new growth and flowers are flushed with purple and the trees are sensitive to frost. • Ethrog or Etrog citron is a variety of citron commonly used in the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles. The flesh is pale yellow and acidic, but not very juicy. The fruits hold well on the tree. The aromatic fruit is considerably larger than a lemon. • The yellow rind is glossy, thick and bumpy. Citron rind is traditionally candied for use in holiday fruitcake. Ethrog or Etrog citron CITRON Citrus medica • Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron is a unique citrus grown mainly as a curiosity. The six to twelve inch fruits are apically split into a varying number of segments that are reminiscent of a human hand. • The rind is yellow and highly fragrant at maturity. The interior of the fruit is solid rind with no flesh or seeds. • Fingered citron fruits usually mature in late fall to early winter and hold moderately well on the tree, but not as well as other citron varieties. Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron NAVEL ORANGES Citrus sinensis • ‘Washington navel orange’ is also known • ‘Lane Late Navel’ was the first of a as the Bahia. It was imported into the number of late maturing Australian United States in 1870. navel orange bud sport selections of Washington navel imported into • These exceptionally delicious, seedless, California. -

WO 2013/077900 Al 30 May 2013 (30.05.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/077900 Al 30 May 2013 (30.05.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A23G 3/00 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (21) International Application Number: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, PCT/US20 12/028 148 KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (22) International Filing Date: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 7 March 2012 (07.03.2012) OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (25) Filing Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 13/300,990 2 1 November 201 1 (21. 11.201 1) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, (72) Inventor; and TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant : CROWLEY, Brian [US/US]; 104 Palisades DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, Avenue, #2B, Jersey City, New Jersey 07306 (US). -

Nuclear Species-Diagnostic SNP Markers Mined from 454 Amplicon Sequencing Reveal Admixture Genomic Structure of Modern Citrus Varieties

RESEARCH ARTICLE Nuclear Species-Diagnostic SNP Markers Mined from 454 Amplicon Sequencing Reveal Admixture Genomic Structure of Modern Citrus Varieties Franck Curk1,2, Gema Ancillo2, Frédérique Ollitrault2, Xavier Perrier3, Jean- Pierre Jacquemoud-Collet3, Andres Garcia-Lor2, Luis Navarro2*, Patrick Ollitrault2,4* 1 Unité Mixte de Recherche Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes (UMR Agap), Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (Inra), Centre Inra de Corse, F-20230, San Giuliano, Corsica, France, 2 Centro de Protección Vegetal y Biotecnología, Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias (Ivia), 46113, Moncada, Valencia, Spain, 3 Unité Mixte de Recherche Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes (UMR Agap), Centre de coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (Cirad), TA A-108/02, 34398, Montpellier, Cedex 5, France, 4 Unité Mixte de Recherche Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes (UMR Agap), Centre de coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (Cirad), Station de Roujol, 97170, Petit-Bourg, Guadeloupe, France OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (LN); [email protected] (PO) Citation: Curk F, Ancillo G, Ollitrault F, Perrier X, Jacquemoud-Collet J-P, Garcia-Lor A, et al. (2015) Nuclear Species-Diagnostic SNP Markers Mined from 454 Amplicon Sequencing Reveal Admixture Abstract Genomic Structure of Modern Citrus Varieties. PLoS Most cultivated Citrus species originated from interspecific hybridisation between four an- ONE 10(5): e0125628. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0125628 cestral taxa (C. reticulata, C. maxima, C. medica, and C. micrantha) with limited further inter- specific recombination due to vegetative propagation. This evolution resulted in admixture Academic Editor: David D Fang, USDA-ARS- SRRC, UNITED STATES genomes with frequent interspecific heterozygosity. -

Perennial Edible Fruits of the Tropics: an and Taxonomists Throughout the World Who Have Left Inventory

United States Department of Agriculture Perennial Edible Fruits Agricultural Research Service of the Tropics Agriculture Handbook No. 642 An Inventory t Abstract Acknowledgments Martin, Franklin W., Carl W. Cannpbell, Ruth M. Puberté. We owe first thanks to the botanists, horticulturists 1987 Perennial Edible Fruits of the Tropics: An and taxonomists throughout the world who have left Inventory. U.S. Department of Agriculture, written records of the fruits they encountered. Agriculture Handbook No. 642, 252 p., illus. Second, we thank Richard A. Hamilton, who read and The edible fruits of the Tropics are nnany in number, criticized the major part of the manuscript. His help varied in form, and irregular in distribution. They can be was invaluable. categorized as major or minor. Only about 300 Tropical fruits can be considered great. These are outstanding We also thank the many individuals who read, criti- in one or more of the following: Size, beauty, flavor, and cized, or contributed to various parts of the book. In nutritional value. In contrast are the more than 3,000 alphabetical order, they are Susan Abraham (Indian fruits that can be considered minor, limited severely by fruits), Herbert Barrett (citrus fruits), Jose Calzada one or more defects, such as very small size, poor taste Benza (fruits of Peru), Clarkson (South African fruits), or appeal, limited adaptability, or limited distribution. William 0. Cooper (citrus fruits), Derek Cormack The major fruits are not all well known. Some excellent (arrangements for review in Africa), Milton de Albu- fruits which rival the commercialized greatest are still querque (Brazilian fruits), Enriquito D. -

These Fruiting Plants Will Tolerate Occasional Temperatures at Or Below Freezing

These fruiting plants will tolerate occasional temperatures at or below freezing. Although many prefer temperatures not below 40 degrees F., all will fruit in areas with winter temperatures that get down to 32 degrees F. Some plants may need frost protection when young. Some will survive temperatures into the mid or low 20’s F. or below. Most of these plants have little or no chilling requirements. Chill Hours • As the days become shorter and cooler in fall, some plants stop growing, store energy, and enter a state of dormancy which protects them from the freezing temperatures of winter. (deciduous plants lose their leaves ) Once dormant, a deciduous fruit tree will not resume normal growth, including flowering and fruit set, until it has experienced an amount of cold equal to its minimum “chilling requirement” followed by a certain amount of heat. • A simple and widely used method is the Hours Below 45°F model which equates chilling to the total number of hours below 45°F during the dormant period, autumn leaf fall to spring bud break. These hours are termed “chill hours”. • Chill hour requirements may vary How a fruit tree actually accumulates winter from fruit type to fruit type or chilling is more complex . Research indicates even between cultivars or varieties fruit tree chilling: of the same type of fruit. 1) does not occur below about 30-34°F, 2) occurs also above 45°F to about 55°F, • Chill hour requirements may be as 3) is accumulated most effectively in the 35-50°F high as 800 chill hours or more or range, as low as 100 chill hours or less. -

The Citrus Notes of Fragrance, 2012

The Citrus Notes of Fragrance Glen O. Brechbill Fragrance Books Inc. www.perfumerbook.com New Jersey - USA 2012 Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com The Citrus Notes “To my late much loved father Ray and beloved mother Helen Roberta without them non of this work would have been possible” II THE CITRUS NOTES OF FRAGRANCE © This book is a work of non-fiction. No part of the book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Please note the enclosed book is based on Fragrance Ingredients by House ©. Designed by Glen O. Brechbill Library of Congress Brechbill, Glen O. The Citrus Notes of Fragrance / Glen O. Brechbill P. cm. 220 pgs. 1. Fragrance Ingredients Non Fiction. 2. Written odor descriptions to facillitate the understanding of the olfactory language. 1. Essential Oils. 2. Aromas. 3. Chemicals. 4. Classification. 5. Source. 6. Art. 7. Twenty one thousand fragrances. 8. Science. 9. Creativity. I. Title. Certificate Registry # Copyright © 2012 by Glen O. Brechbill All Rights Reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com The Citrus Notes of Fragrance About the Book What is this book about one asks? other then trace amounts. Its a The fragrance, which you are pur- To put it as simply as possible it is shame that this legislation is slowly chasing, includes the following nat- about the major citrus notes that are destroying the classic fragrances ural or essential oils. -

Genetic Variation of Fruit Characteristics in Kiyomi

GENETIC VARIABILITY OF FRUIT CHARACTERISTICS IN KIYOMI TANGOR PROGENIES OF CITRUS NICOLA KIM COMBRINK Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the MSc Plant Breeding degree in the faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Department of Plant Breeding at the University of the Free State November 2011 Promoter: Prof. Maryke Labuschagne Co-promoter: Zelda Bijzet i CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 REFERENCES 3 2. LITERATURE REVIEW: THE GENETIC IMPROVEMENT OF CITRUS 5 INTRODUCTION 5 THE HISTORY OF CITRUS BREEDING 6 CONTROLLED POLLINATIONS AND RAISING SEEDLINGS FOR BREEDING PURPOSES 6 EVALUATION OF F1 HYBRIDS 8 BREEDING OBJECTIVES 8 Breeding for fruit quality 9 Breeding for industrial purposes 9 Breeding for resistance to pests and diseases 10 Breeding for hardy cultivars 10 Breeding for improved rootstocks 10 OBSTACLES IN CITRUS BREEDING 10 Incompatibility 11 Sterility 12 Poly-embryony / Nucellar embryony / Apomixis 12 Heterozygosity 14 The juvenile period 14 GENETIC VARIABILITY IN CITRUS 14 HYBRIDISATION IN CITRUS 15 INHERITANCE OF CHARACTERISTICS 16 THE ESTIMATION OF HERITABILITY IN FRUIT TREE BREEDING 17 Repeatability 18 The intraclass correlation coefficient 19 SELECTION OF PARENTS 21 INBREEDING IN CITRUS 21 POLYPLOIDY IN CITRUS 22 MUTATIONS IN CITRUS 23 THE USE OF BIOTECHNOLOGY TO ASSIST CITRUS BREEDING 24 CONCLUSIONS 28 ii REFERENCES 28 3. GENOTYPIC VARIATION OF RIND COLOUR IN KIYOMI TANGOR FAMILIES 33 INTRODUCTION 33 MATERIALS AND METHODS 35 Experimental site 35 Selection of families 35 Determination of sample size 37 Data collection 40 Data analysis 41 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 42 CONCLUSIONS 60 REFERENCES 62 4. GENOTYPIC VARIATION IN FRUIT SIZE AND SHAPE IN KIYOMI FAMILIES 64 INTRODUCTION 64 MATERIALS AND METHODS 67 Selection of families 67 Sampling of trees and fruit for evaluation 68 Data collection 69 Data analysis 69 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 69 CONCLUSIONS 87 REFERENCES 89 5.