The Muscovite State and Its Personnel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1 Ivan Sablin University of Heidelberg Kuzma Kukushkin Peter the Great Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University Abstract Focusing on the term zemskii sobor, this study explored the historiographies of the early modern Russian assemblies, which the term denoted, as well as the autocratic and democratic mythologies connected to it. Historians have discussed whether the individual assemblies in the sixteenth and seventeenth century could be seen as a consistent institution, what constituencies were represented there, what role they played in the relations of the Tsar with his subjects, and if they were similar to the early modern assemblies elsewhere. The growing historiographic consensus does not see the early modern Russian assemblies as an institution. In the nineteenth–early twentieth century, history writing and myth-making integrated the zemskii sobor into the argumentations of both the opponents and the proponents of parliamentarism in Russia. The autocratic mythology, perpetuated by the Slavophiles in the second half of the nineteenth century, proved more coherent yet did not achieve the recognition from the Tsars. The democratic mythology was more heterogeneous and, despite occasionally fading to the background of the debates, lasted for some hundred years between the 1820s and the 1920s. Initially, the autocratic approach to the zemskii sobor was idealistic, but it became more practical at the summit of its popularity during the Revolution of 1905–1907, when the zemskii sobor was discussed by the government as a way to avoid bigger concessions. Regionalist approaches to Russia’s past and future became formative for the democratic mythology of the zemskii sobor, which persisted as part of the romantic nationalist imagery well into the Russian Civil War of 1918–1922. -

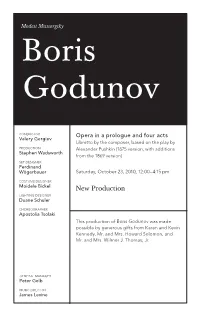

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012 Department of History Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843-4236 (979) 845-7166 e-mail: [email protected] DEGREES RECEIVED: B.A. University of California at Santa Cruz 1971 Highest Honors in History, College Honors M.A. Boston College 1972 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, American history to 1900 Ph.D. Boston College 1976 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, Comparative early modern European history, American history to Reconstruction ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Lecturer Boston College 1975-76 Assistant Professor Pembroke State University 1977-79 University Honors Professor Pembroke State University 1978-79 Assistant Professor Texas A&M University 1979-85 Associate Professor Texas A&M University 1985-2002 Visiting Scholar Harvard University 1987-88 Professor Texas A&M University 2002- Eppright Professor Texas A&M University 2005-2008 Fasken Chair Texas A&M University 2012- Fulbright Visiting Professor University of Aberdeen, Scotland 2013 TEACHING FIELDS: UNDERGRADUATE Russian Civilization Medieval and Early Modern Russian History Early Modern Europe Rise of the European Middle Class Imperial Russia, 1801-1917 History of the Soviet Union Eastern Europe Since 1453 Western Civilization 2 TEACHING FIELDS: GRADUATE Early Modern Russia Early Modern Europe Medieval Russia Imperial Russia The Russian Revolution and Civil War Historiography SUPERVISION OF INDEPENDENT GRADUATE WORK: Chair M.A. Committee Ann Todd Baum Completed, 1985 Chair M.A. Committee Cassandra Bell Completed, 1991 Chair M.A. Committee James Vargas Completed, 1993 Chair M.A. Committee Lisa Tauferner Completed, 2007 Chair M.A. Committee Mark Douglass Completed, 2009 Chair M.A. -

Historic Centre of the City of Yaroslavl”

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1170.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Historical Centre of the City of Yaroslavl DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 15th July 2005 STATE PARTY: RUSSIAN FEDERATION CRITERIA: C (ii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (ii): The historic town of Yaroslavl with its 17th century churches and its Neo-classical radial urban plan and civic architecture is an outstanding example of the interchange of cultural and architectural influences between Western Europe and Russian Empire. Criterion (iv): Yaroslavl is an outstanding example of the town-planning reform ordered by Empress Catherine The Great in the whole of Russia, implemented between 1763 and 1830. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Situated at the confluence of the Volga and Kotorosl rivers some 250km northeast of Moscow, the historic city of Yaroslavl developed into a major commercial centre as of the 11th century. It is renowned for its numerous 17th-century churches and is an outstanding example of the urban planning reform Empress Catherine the Great ordered for the whole of Russia in 1763. While keeping some of its significant historic structures, the town was renovated in the neo-classical style on a radial urban master plan. It has also kept elements from the 16th century in the Spassky Monastery, one of the oldest in the Upper Volga region, built on -

The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin's Narrative

European Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, 143–157 © 2018 Academia Europæa doi:10.1017/S1062798718000650 The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin’s Narrative DMITRY SHLAPENTOKH DW 332, Indiana University South Bend, 1700 Mishawaka Avenue, South Bend, IN 46615, USA. Email: [email protected] Alexander Dugin (b. 1962) is one of the best-known philosophers and public intellectuals of post-Soviet Russia. While his geopolitical views are well-researched, his views on Russian history are less so. Still, they are important to understand his Weltanschauung and that of like-minded Russian intellectuals. For Dugin, the ‘Time of Troubles’–the period of Russian history at the beginning of the seven- teenth century marked by dynastic crisis and general chaos – constitutes an expla- natory framework for the present. Dugin implicitly regarded the ‘Time of Troubles’ in broader philosophical terms. For him, the ‘Time of Troubles’ meant not purely political and social upheaval/dislocation, but a deep spiritual crisis that endangered the very existence of the Russian people. Russia, in his view, has undergone several crises during its long history. Each time, however, Russia has risen again and achieved even greater levels of spiritual wholeness. Dugin believed that Russia was going through a new ‘Time of Troubles’. In the early days of the post-Soviet era, he believed that it was the collapse of the USSR that had led to a new ‘Time of Troubles’. Later, he changed his mind and proclaimed that the Soviet regime was not legitimate at all and, consequently, that the ‘Time of Troubles’ started a century ago in 1917. -

In Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and the Alexander Palace Association the ALEXANDER PALACE

THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE \ ~ - , •I I THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REpORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE Mission I: February 9-15, 1995 Mission II: June 26-29,1995 Mission III: July 22-26, 1996 THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association June 1997 Enfilade, circa 1945 showing war damage (courtesy Tsarskoe Selo Museum) The research and compilation of this report have been made possible by generous grants from the following contributors Delta Air Lines The Samuel H. Kress Foundation The Charles and Betti Saunders Foundation The Trust for Mutual Understanding Cover: The Alexander Palace, February 1995. Photograph by Kirk Tuck & Michael Larvey. Acknowledgements The World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, and Henry Joyce wish to extend their gratitude to all who made possible the series of international missions that resulted in this document. The World Monuments Fund's initial planning mission to St. Petersburg in 1995 was organized by the office of Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and the members of the Alexander Palace Association. The planning team included representatives of the World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, and the Alexander Palace Association, accompanied by Henry Joyce. This preliminary report and study tour was made possible by grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Trust for Mutual Understanding. -

Download Free Sampler

Thank you for downloading this free sampler of: WRITING THE TIME OF TROUBLES False Dmitry in Russian Literature MARCIA A. MORRIS Series: The Unknown Nineteenth Century August 2018 | 192 pp. 9781618118639 | $99.00 | Hardback SUMMARY . Is each moment in history unique, or do essential situations repeat themselves? The traumatic events associated with the man who reigned as Tsar Dmitry have haunted the Russian imagination for four hundred years. Was Dmitry legitimate, the last scion of the House of Rurik, or was he an upstart pretender? A harbinger of Russia’s doom or a herald of progress? Writing the Time of Troubles traces the proliferation of fictional representations of Dmitry in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russia, showing how playwrights and novelists reshaped and appropriated his brief and equivocal career as a means of drawing attention to and negotiating the social anxieties of their own times. ABOUT THE AUTHOR . Marcia A. Morris is Professor of Slavic Languages at Georgetown University. She is the author of Saints and Revolutionaries: The Ascetic Hero in Russian Literature, The Literature of Roguery in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Russia, and Russian Tales of Demonic Possession: Translations of Savva Grudtsyn and Solomonia. 20% off with the promotional code MORRIS at www.academicstudiespress.com Free sampler. Copyrighted material. WRITING THE TIME OF TROUBLES False Dmitry in Russian Literature Free sampler. Copyrighted material. The Unknown Nineteenth Century Series Editor JOE PESCHIO (University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee) Editorial Board ANGELA BRINTLINGER (Ohio State University, Columbus) ALYSSA GILLESPIE (University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana) MIKHAIL GRONAS (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire) IGOR PILSHCHIKOV (Tallinn University, Moscow State University) DAVID POWELSTOCK (Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts) ILYA VINITSKY (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) Free sampler. -

Advertising 1

advertising 1. В английском тексте вместо * ставь 123. Текст 123 выделен желтым 2. В русском тексте 123 обрати внимание фраза 2 скорректирована. Ее так же необходимо изменить 3. Сами цифры 123 должны быть меньшего размера чем текст в обоих версиях 4. Фраза в англ версии спикинг на коннектинг вчерашний файл прикладываю 5. Пункт V-Tell phone numbers of…. Его надо сократить убрав последних два предложения про выбор номера и визитки 6. Проверь орфографию и дублирования всякие. Это крайня я версия ее в печать Жду V - T E L L . R U 1. Из перечня стран, указанного на сайте v-tell.ru 2. В пределах доступных в системе номеров 3. При наличии номера страны вызывающего абонента TO PARTICIPANTS, GUESTS AND ORGANIZERS OF THE ST. PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC FORUM DEAR FRIENDS, It is a great pleasure to welcome you to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, which this year is taking place under the theme Achieving a New Balance in the Global Economic Arena. For the first time in the last several years, the global economy is showing signs of recovery. The Forum will discuss how to consolidate the emerging trends and assess the risks and challenges related to the introduction of new technologies. The sweeping changes taking place today require effective measures by the international community to enhance the international governance architecture in order to take coordinated steps to ensure that all population groups benefit from the fruits of globalization and thereby guarantee sustainable and balanced development. Over these years, the Forum has gained substantial authority as a recognized global discussion platform open for direct and engaged dialogue on the relevant issues we face today. -

The Fourth German-Russian Week of the Young Researcher

THE FOURTH GERMAN-RUSSIAN WEEK OF THE YOUNG RESEARCHER “GLOBAL HISTORY. GERMAN-RUSSIAN PERSPECTIVES ON REGIONAL STUDIES” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 Impressum “The Fourth German-Russian Week of the Young Researcher” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 Editors: Dr. Gregor Berghorn, DAAD / DWIH Moscow Dr. Jörn Achterberg, DFG Office Russia / CIS Julia Ilina (DFG) Layout by: “MaWi group” AG / Moskauer Deutsche Zeitung Photos by: DWIH, DFG, SPSU Moscow, December 2014 Printed by: LLC “Tverskoy Pechatny Dvor” Supported by Federal Foreign Office THE FOURTH GERMAN-RUSSIAN WEEK OF THE YOUNG RESEARCHER “GLOBAL HISTORY. GERMAN-RUSSIAN PERSPECTIVES ON REGIONAL STUDIES” Saint Petersburg, October 6–10, 2014 ТABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Preface Prof. Dr. Stefan Rinke, Polina Rysakova, Dr. Gregor Berghorn / Dr. Jörn Achterberg 3 Freie Universität Berlin 37 Saint Petersburg State University 58 Prof. Dr. Aleksandr Kubyshkin, Ivan Sablin, Welcoming Addresses Saint Petersburg State University 38 National Research University “Higher School of Economics”, St. Petersburg 59 Prof. Dr. Nikolai Kropachev, Contributions of Young German and Russian Andrey Shadursky, Rector of the Saint Petersburg State University 4 Researchers Saint Petersburg State University 60 Dr. Heike Peitsch, Anna Shcherbakova, Consul General of the Federal Republic of Germany Monika Contreras Saiz, Institute of Latin America, RAS, Moscow 61 in St. Petersburg 6 Freie Universität Berlin 40 Natalia Toganova, Prof. Dr. Margret Wintermantel, Franziska Davies, Institute of World Economy and International President of the DAAD 9 Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich 41 Relations (IMEMO RAN), Moscow 62 Prof. Dr. Peter Funke, Jürgen Dinkel, Max Trecker, Vice-President of the DFG 13 Justus-Liebig-University Giessen 42 Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich 64 Dr. -

517 the Rise of Michael the Archangel – the Time of Troubles, Part 6, the Election of Mikhail Romanov Delivers Russia from the Time of Troubles

#517 The Rise of Michael the Archangel – The Time of Troubles, part 6, The Election of Mikhail Romanov delivers Russia from The Time of Troubles [This continues the story of The Time of Troubles.] Poland rules Russia. It was King Sigismund III of Poland who supported the first False Dmitri and the second False Dmitri. Polish troops entered Moscow in 1610 in defense of the second False Dmitri, but he was killed. In the meantime during that year, a group of seven boyars threw down Vasili Shuisky and ratified a treaty with the Polish king, inviting his son Ladislas IV to the Russian throne. The Poles ruled through a powerless council of boyars until 1612. In the meantime, King Sigismund III decided that he wanted to rule there himself (instead of having his son on the throne). He succeeded only in uniting the Russians against the Polish invaders, and Russian forces under Prince Dimitri Pozharsky finally retook Moscow in October 1612. Dmitry Pozharsky is asked to lead The Poles surrender the Moscow Kremlin the volunteer army against the Poles. to Prince Pozharsky in 1612. Painting by Vasily Savinsky (1882). Painting by Ernest Lissner. The Election of Michael Romanov. After the Poles were defeated, there was no one of royal birth to take the throne. In 1613, the Zemskii Sobor (a national council dominated by the boyars) unanimously elected as tsar 17-year-old Michael Romanov. The name Romanov had been taken from Roman Yuriev, the father of Anastasia Romanovna, who was the first wife of Ivan the Terrible. Michael Romanov was the grandnephew of Anastasia. -

7 Pushkin's Boris Godunov

7 PUSHKIN’S BORIS GODUNOV A chance encounter with Musorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov as a teenager was the beginning of a love aff air with Pushkin’s 1825 history play, and with the composer of its most famous operatic transposition, that has lasted to the present day. It worked itself out through a dissertation, a book, several decades of delivering lecture-recitals on the Russian “realistic” art song (Dargomyzhsky and Musorgsky), and in 2006 culminated on a fascinating production of the play planned by Vsevolod Meyerhold, with music by Sergei Prokofi ev, for the 1937 (“Stalinist”) Pushkin Jubilee. Th at production (along with much else in the fi rst year of the Great Terror) never made it to opening night. It was my good fortune, in 2007, to co-manage at Princeton University a “re- invention” of this aborted 1936 production of Pushkin’s drama (see Chapter 20). Th e central textbook for that all-campus project, acquainting Princeton’s director and cast with the author, period, history, and play, was a recent volume by Chester Dunning (with contributions from myself and two Russian Pushkinists): Th e Uncensored Boris Godunov: Th e Case for Pushkin’s Original “Comedy” (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006). Th e volume as a whole defended the unpublished 1825 version of the play and Pushkin’s excellence as an historian (not only as a playwright) during the mid-1820s. Dunning’s book also contained a new acting English translation of the 1825 play by Antony Wood. Th e excerpt below, from my chapter 5, continues the debate around Bakhtin’s carnival, suggests the genre of a “tragicomedy of history,” and revises an idea about the working of time already sounding at the end of “Tatiana”: if indeed there can be reversible and irreversible heroes in a history play, then Pushkin creates his Pretender as the former, his Tsar Boris as the latter. -

The Time of Troubles, Part 4, Dealing with False Dmitri

#515 The Rise of Michael the Archangel – The Time of Troubles, part 4, Dealing with False Dmitri [This continues the story of The Time of Troubles.] Key Understanding: The Time of Troubles in Russia in the early 1600’s was a part of the fulfillment of Daniel 12:1. Daniel 12:1 (KJV) And at that time SHALL MICHAEL [the Archangel] STAND UP, the great prince which standeth for the children of thy people: and there shall be A TIME OF TROUBLE, such as never was since there was a nation even to that same time: and at that time thy people shall be delivered, every one that shall be found written in the book. Answering the cry of the Russian people, a young man claiming to be Dmitri, the son of Ivan IV, had surfaced, ready to take the throne that was “rightfully” his. False Dmitri spent a short time in Moscow in 1601, where he was pursued by the law because of his claims. He fled to Poland to plan his return. In Poland, the pretender became Roman Catholic and promised the Jesuits to Catholicize Russia upon seizing power, in exchange for their aid in his one-man invasion. In 1604, while Boris Godunov was still tsar, False Dmitri headed eastward to Kiev, joined along the way by bands of Cossacks, eager to topple Godunov’s position. Pushed back at once by the defending armies of the tsar, he eventually arrived at Moscow with a force of 1500 Cossacks, adventurers, Polish mercenaries, and others eager to march into the city.