Download Free Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of a Superpower, Foundation of the Russian Empire

Russian History: The Rise of a Superpower, Foundation of the Russian Empire Part II. From the Reinforcement of Tsardom to the Congress of Vienna By Julien Paolantoni Region: Russia and FSU Global Research, March 08, 2018 Theme: History 15 December 2012 Relevant article selected from the GR archive, first published on GR in December 2012 Introduction Part 1 of this series Russian History: From the Early East Slavs to the Grand Duchy of Moscow was aimed at explaining the foundation of the Russian state, by discussing its early influences in the cultural and political fields. As the subject of the present part is to provide insight on how Russia reached the status of superpower, it is necessary to briefly get back to the reign of Ivan III. Although the reign of the tsars started officially with Ivan IV, Ivan III (“Ivan the Great”) played a critical role in the centralization of the Russian state, after having defeated the Mongol army in 1480. Meanwhile, the extension of the Russian land was eased by the death of Casimir IV, the king of Poland, in 1492 and the fact that Casimir’s son, Alexander, was willing to cooperate with the Russians, so he wedded Ivan’s daughter Helena soon after accessing the throne of Lithuania, as an attempt to avoid open conflict with his powerful neighbor. Unfortunately for him, Ivan III’s clear determination to appropriate as much of Lithuania as possible, finally obliged Alexander to wage war against his father-in-law in 1499. It was a complete disaster for Lithuania and in 1503 Alexander eventually purchased peace by ceding to Ivan III Novgorod-Seversky, Chernigov and seventeen other cities. -

Akathist-Hymn-To-Our-Lady-Of-Kazan

Akathist Hymn to the Virgin of Kazan Our Lady of Kazan According to tradition, the original icon of Our Lady of Kazan was brought to Russia from Constantinople in the 13th century. After the establishment of the Khanate of Kazan (c. 1438) the icon disappeared from the historical record for more than a century. Metropolitan Hermogenes' chronicle, written at the request of Tsar Feodor in 1595, describes the recovery of the icon. According to this account, after a fire destroyed Kazan in 1579, the Virgin appeared to a 10-year-old girl, Matrona, revealing the location where the icon lay hidden. The girl told the archbishop about the dream but she was not taken seriously. However, on 8 July 1579, after two repetitions of the dream, the girl and her mother recovered the icon on their own, buried under a destroyed house where it had been hidden to save it from the Tatars. Other churches were built in honour of the revelation of the Virgin of Kazan, and copies of the image were displayed at the Kazan Cathedral of Moscow (constructed in the early 17th century), at Yaroslavl, and at St. Petersburg. Russian military commanders Dmitry Pozharsky (17th century) and Mikhail Kutuzov (19th century) credited i invocation of the Virgin Mary through the icon with helping the country to repel the Polish invasion of 1612, the Swedish invasion of 1709, and Napoleon's invasion of 1812. The Kazan icon achieved immense popularity, and there were nine or ten separate miracle-attributed copies of the icon around Russia. On the night of June 29, 1904, the icon was stolen from the Kazan Convent of the Theotokos in Kazan where it had been kept for centuries (the building was later blown up by the communist authorities. -

Summarized by © Lakhasly.Com He Managed to Hang on to The

He managed to hang on to the throne for four years despite a series of upheavals, starting with uprisings by various boyar rivals. Shuisky also survived a widespread rebellion of peasants, serfs, slaves, and other dispossessed groups led by the Cossack Ivan Bolotnikov, which aimed to overthrow the entire social order and lasted until 1607. Meanwhile, a second False Dmitry crossed the frontier with Polish backing. When Shuisky turned to Sweden for help—giving up Russia’s claim to disputed territory in return—Poland, a rival of both Sweden and Russia, entered the war directly. Amid this swirling, destructive confusion, Shuisky was driven from the throne in 1610 and a small group of boyars took control in Moscow. Russia then hit bottom. That summer, besieged by two armies, one Polish and the other a Russian force loyal to the second False Dmitry, a hastily convened group of boyars in Moscow elected the son of the Polish king to be Russia’s czar; in return the Poles quickly disposed of the second False Dmitry. Yet, as it turned out, there was a sufficiently robust sense of identity and potential unity for Muscovy to generate its own revival, especially when faced with the threat of domination by ‘heretics’. The decisive factors were Orthodoxy as the national religion, symbolized by the Patriarch, and the resourcefulness of local communities in organizing resistance. When one boyar clan prepared to welcome the Polish royal heir Władisław as constitutional monarch in a personal union with the Polish crown, Patriarch Germogen reacted by insisting that no one should swear loyalty to a Catholic ruler. -

Birthright Democracy: Nationhood and Constitutional Self-Government in History

BIRTHRIGHT DEMOCRACY: NATIONHOOD AND CONSTITUTIONAL SELF-GOVERNMENT IN HISTORY By Ethan Alexander-Davey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2013 Date of final oral examination: 8/16/13 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Richard Avramenko, Political Science Daniel Kapust, Political Science James Klausen, Political Science Howard Schweber, Political Science Johann Sommerville, History i Abstract How did constitutionally limited government and democracy emerge in the West? Many scholars from many different perspectives have attempted to answer this question. I identify the emergence of these forms of self-government with early modern nationalism. Broadly speaking, nationalism of the right sort provides indispensable resources both for united popular resistance against autocratic rule, and for the formation and legitimation of national systems self- governance. Resistance and self-government both require a national consciousness that includes a myth of national origin, a national language, a common faith, and, crucially, native traditions of self-government, and stories of heroic ancestors who successfully defended those traditions against usurpers and tyrants. It is through national consciousness that abstract theories of resistance and self-government become concrete and tenable. It is though national fellowship that the idea of a political nation, possessing the right to make rulers accountable to its will, comes into existence and is sustained over time. My arguments basically fall under two headings, historical and theoretical. By an examination of the nationalist political thought of early modern European countries, I intend to establish important historical connections between the rise of nationalism and the emergence of self-government. -

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1 Ivan Sablin University of Heidelberg Kuzma Kukushkin Peter the Great Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University Abstract Focusing on the term zemskii sobor, this study explored the historiographies of the early modern Russian assemblies, which the term denoted, as well as the autocratic and democratic mythologies connected to it. Historians have discussed whether the individual assemblies in the sixteenth and seventeenth century could be seen as a consistent institution, what constituencies were represented there, what role they played in the relations of the Tsar with his subjects, and if they were similar to the early modern assemblies elsewhere. The growing historiographic consensus does not see the early modern Russian assemblies as an institution. In the nineteenth–early twentieth century, history writing and myth-making integrated the zemskii sobor into the argumentations of both the opponents and the proponents of parliamentarism in Russia. The autocratic mythology, perpetuated by the Slavophiles in the second half of the nineteenth century, proved more coherent yet did not achieve the recognition from the Tsars. The democratic mythology was more heterogeneous and, despite occasionally fading to the background of the debates, lasted for some hundred years between the 1820s and the 1920s. Initially, the autocratic approach to the zemskii sobor was idealistic, but it became more practical at the summit of its popularity during the Revolution of 1905–1907, when the zemskii sobor was discussed by the government as a way to avoid bigger concessions. Regionalist approaches to Russia’s past and future became formative for the democratic mythology of the zemskii sobor, which persisted as part of the romantic nationalist imagery well into the Russian Civil War of 1918–1922. -

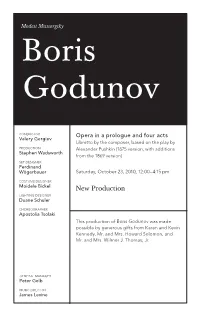

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012 Department of History Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843-4236 (979) 845-7166 e-mail: [email protected] DEGREES RECEIVED: B.A. University of California at Santa Cruz 1971 Highest Honors in History, College Honors M.A. Boston College 1972 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, American history to 1900 Ph.D. Boston College 1976 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, Comparative early modern European history, American history to Reconstruction ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Lecturer Boston College 1975-76 Assistant Professor Pembroke State University 1977-79 University Honors Professor Pembroke State University 1978-79 Assistant Professor Texas A&M University 1979-85 Associate Professor Texas A&M University 1985-2002 Visiting Scholar Harvard University 1987-88 Professor Texas A&M University 2002- Eppright Professor Texas A&M University 2005-2008 Fasken Chair Texas A&M University 2012- Fulbright Visiting Professor University of Aberdeen, Scotland 2013 TEACHING FIELDS: UNDERGRADUATE Russian Civilization Medieval and Early Modern Russian History Early Modern Europe Rise of the European Middle Class Imperial Russia, 1801-1917 History of the Soviet Union Eastern Europe Since 1453 Western Civilization 2 TEACHING FIELDS: GRADUATE Early Modern Russia Early Modern Europe Medieval Russia Imperial Russia The Russian Revolution and Civil War Historiography SUPERVISION OF INDEPENDENT GRADUATE WORK: Chair M.A. Committee Ann Todd Baum Completed, 1985 Chair M.A. Committee Cassandra Bell Completed, 1991 Chair M.A. Committee James Vargas Completed, 1993 Chair M.A. Committee Lisa Tauferner Completed, 2007 Chair M.A. Committee Mark Douglass Completed, 2009 Chair M.A. -

Historic Centre of the City of Yaroslavl”

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1170.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Historical Centre of the City of Yaroslavl DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 15th July 2005 STATE PARTY: RUSSIAN FEDERATION CRITERIA: C (ii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (ii): The historic town of Yaroslavl with its 17th century churches and its Neo-classical radial urban plan and civic architecture is an outstanding example of the interchange of cultural and architectural influences between Western Europe and Russian Empire. Criterion (iv): Yaroslavl is an outstanding example of the town-planning reform ordered by Empress Catherine The Great in the whole of Russia, implemented between 1763 and 1830. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Situated at the confluence of the Volga and Kotorosl rivers some 250km northeast of Moscow, the historic city of Yaroslavl developed into a major commercial centre as of the 11th century. It is renowned for its numerous 17th-century churches and is an outstanding example of the urban planning reform Empress Catherine the Great ordered for the whole of Russia in 1763. While keeping some of its significant historic structures, the town was renovated in the neo-classical style on a radial urban master plan. It has also kept elements from the 16th century in the Spassky Monastery, one of the oldest in the Upper Volga region, built on -

Abrief History

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RUSSIA i-xxiv_BH-Russia_fm.indd i 5/7/08 4:03:06 PM i-xxiv_BH-Russia_fm.indd ii 5/7/08 4:03:06 PM A BRIEF HISTORY OF RUSSIA MICHAEL KORT Boston University i-xxiv_BH-Russia_fm.indd iii 5/7/08 4:03:06 PM A Brief History of Russia Copyright © 2008 by Michael Kort The author has made every effort to clear permissions for material excerpted in this book. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kort, Michael, 1944– A brief history of Russia / Michael Kort. p. cm.—(Brief history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8160-7112-8 ISBN-10: 0-8160-7112-8 1. Russia—History. 2. Soviet Union—History. I. Title. DK40.K687 2007 947—dc22 2007032723 The author and Facts On File have made every effort to contact copyright holders. The publisher will be glad to rectify, in future editions, any errors or omissions brought to their notice. We thank the following presses for permission to reproduce the material listed. Oxford University Press, London, for permission to reprint portions of Mikhail Speransky’s 1802 memorandum to Alexander I from The Russia Empire, 1801–1917 (1967) by Hugh Seton-Watson. -

The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin's Narrative

European Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, 143–157 © 2018 Academia Europæa doi:10.1017/S1062798718000650 The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin’s Narrative DMITRY SHLAPENTOKH DW 332, Indiana University South Bend, 1700 Mishawaka Avenue, South Bend, IN 46615, USA. Email: [email protected] Alexander Dugin (b. 1962) is one of the best-known philosophers and public intellectuals of post-Soviet Russia. While his geopolitical views are well-researched, his views on Russian history are less so. Still, they are important to understand his Weltanschauung and that of like-minded Russian intellectuals. For Dugin, the ‘Time of Troubles’–the period of Russian history at the beginning of the seven- teenth century marked by dynastic crisis and general chaos – constitutes an expla- natory framework for the present. Dugin implicitly regarded the ‘Time of Troubles’ in broader philosophical terms. For him, the ‘Time of Troubles’ meant not purely political and social upheaval/dislocation, but a deep spiritual crisis that endangered the very existence of the Russian people. Russia, in his view, has undergone several crises during its long history. Each time, however, Russia has risen again and achieved even greater levels of spiritual wholeness. Dugin believed that Russia was going through a new ‘Time of Troubles’. In the early days of the post-Soviet era, he believed that it was the collapse of the USSR that had led to a new ‘Time of Troubles’. Later, he changed his mind and proclaimed that the Soviet regime was not legitimate at all and, consequently, that the ‘Time of Troubles’ started a century ago in 1917. -

In Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and the Alexander Palace Association the ALEXANDER PALACE

THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE \ ~ - , •I I THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REpORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE Mission I: February 9-15, 1995 Mission II: June 26-29,1995 Mission III: July 22-26, 1996 THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association June 1997 Enfilade, circa 1945 showing war damage (courtesy Tsarskoe Selo Museum) The research and compilation of this report have been made possible by generous grants from the following contributors Delta Air Lines The Samuel H. Kress Foundation The Charles and Betti Saunders Foundation The Trust for Mutual Understanding Cover: The Alexander Palace, February 1995. Photograph by Kirk Tuck & Michael Larvey. Acknowledgements The World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, and Henry Joyce wish to extend their gratitude to all who made possible the series of international missions that resulted in this document. The World Monuments Fund's initial planning mission to St. Petersburg in 1995 was organized by the office of Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and the members of the Alexander Palace Association. The planning team included representatives of the World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, and the Alexander Palace Association, accompanied by Henry Joyce. This preliminary report and study tour was made possible by grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Trust for Mutual Understanding. -

Advertising 1

advertising 1. В английском тексте вместо * ставь 123. Текст 123 выделен желтым 2. В русском тексте 123 обрати внимание фраза 2 скорректирована. Ее так же необходимо изменить 3. Сами цифры 123 должны быть меньшего размера чем текст в обоих версиях 4. Фраза в англ версии спикинг на коннектинг вчерашний файл прикладываю 5. Пункт V-Tell phone numbers of…. Его надо сократить убрав последних два предложения про выбор номера и визитки 6. Проверь орфографию и дублирования всякие. Это крайня я версия ее в печать Жду V - T E L L . R U 1. Из перечня стран, указанного на сайте v-tell.ru 2. В пределах доступных в системе номеров 3. При наличии номера страны вызывающего абонента TO PARTICIPANTS, GUESTS AND ORGANIZERS OF THE ST. PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC FORUM DEAR FRIENDS, It is a great pleasure to welcome you to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, which this year is taking place under the theme Achieving a New Balance in the Global Economic Arena. For the first time in the last several years, the global economy is showing signs of recovery. The Forum will discuss how to consolidate the emerging trends and assess the risks and challenges related to the introduction of new technologies. The sweeping changes taking place today require effective measures by the international community to enhance the international governance architecture in order to take coordinated steps to ensure that all population groups benefit from the fruits of globalization and thereby guarantee sustainable and balanced development. Over these years, the Forum has gained substantial authority as a recognized global discussion platform open for direct and engaged dialogue on the relevant issues we face today.