Boris Godunov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

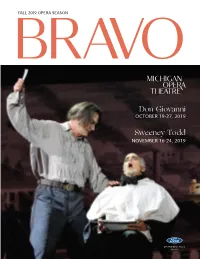

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Musorgsky's Boris Godunov

22 JANUARY 2019 Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov PROFESSOR MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER Today we are going to look at what is possibly the most famous of Russian operas – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Its route to international celebrity is very clear – the great impresario Serge Diaghilev staged it in Paris in 1908, with the star bass Fyodor Chaliapin in the main role. The opera the Parisians saw would have taken Musorgsky by surprise. First, it was staged in a heavily reworked edition made by Rimsky-Korsakov after Musorgsky’s death, where only about 20% of the bars in the original were left unchanged. But that was still a modest affair compared to the steps Diaghilev took on his own initiative. The production had a Russian cast singing the opera in Russian, and Diaghilev was worried that the Parisians would lose patience with scenes that were more wordy, since they would follow none of it, so he decided simply to cut these scenes, even though this meant that some crucial turning points in the drama were lost altogether. He then reordered the remaining scenes to heighten contrasts, jumbling the chronology. In effect, the opera had become a series of striking tableaux rather than a drama with a coherent plot. But as pure spectacle, it was indeed impressive, with astonishing sets provided by the painter Golovin and with the excitement generated by Chaliapin as Boris. For all its shortcomings, it was this production that brought Musorgsky’s masterwork to the world’s attention. 1908, the year of the Paris production was nearly thirty years after Musorgsky’s death, and nearly and forty years after the opera was completed. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

Le-Vite-Dei-Cesenati-10.Pdf

LE VITE DEI CESENATI X A cura di Pier Giovanni Fabbri e Alberto Gagliardo Redazione: Giancarlo Cerasoli, Franco Dell’Amore, Rita Dell’Amore, Paola Errani, Pier Giovanni Fabbri, Alberto Gagliardo. Segretario di redazione: Claudio Medri Consulenza fotografica: Guia Lelli Mami Autori e redattori ringraziano Leonardo Belli, Gessica Boni, Paolo Cascarano (Ana- grafe Ricerche, Comune di Milano), Claudia Colecchia (Fototeca dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte, Trieste), Andrea Daltri (Archivio Storico dell’Università di Bologna), Caterina Del Vivo (Archivio Storico del Gabinetto G.P. Vieusseux, Firenze), Adriana Faedi, Cesare Fantino (Biblioteca Basilica di Santa Maria delle Vigne, Genova), Lu- cia Gandini (Biblioteca di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte, Roma), Barbara Gariboldi (Archivio Storico Civico, Milano), Leila Gentile (Biblioteca Universitaria, Bologna), Ivano Giovannini, Elisabetta Gnecco (Ufficiale dello Stato Civile, Comune di Ge- nova), Antonella Imolesi (Biblioteca Comunale A. Saffi, Forlì), Francesca Mambelli, Marcella Culatti (Fondazione Federico Zeri, Bologna), Elena Mantelli (Biblioteca San Carlo al Corso, Milano), Silvia Mirri (Biblioteca Comunale, Imola), Norma Monta- nari, Claudia Morgan (Fototeca dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte, Trieste), Barbara Mussetto (Biblioteca Casanatense, Roma), Elisabetta Papone (Centro di Documen- tazione per la Storia, l’Arte l’Immagine, Comune di Genova), Massimiliano Pavoni (Biblioteca Mozzi Borgetti, Macerata), Raffaella Ponte (Archivio storico, Comune di Genova), Francesca Sandrini (Museo Glauco Lombardi, Parma), Giampiero Savini, Claudio Schenone (Archivio Storico, Comune di Genova), Bruna Tabarri, Riccardo Vlahov (tecnico e storico della fotografia); il personale dell’Archivio Storico Diocesa- no di Cesena, della Biblioteca Malatestiana di Cesena, degli Archivi di Stato di Cesena e di Forlì. Altri ringraziamenti sono stati espressi nei testi. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #952

Issue No. 952, 28 October 2011 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 1. 'IAEA Report Can Stymie Iran-P5+1 Talks' 2. German Wavers over Sale of Sub to Israel: Report 3. Armenian Nuclear Specialists Move to Iran for Better Life 4. Seoul, US Cautiously Move on 6-Party Talks 5. N. Korea Remains Serious Threat: US Defence Chief 6. Seoul, Beijing Discuss NK Issues 7. Pentagon Chief Doubts N. Korea Will Give Up Nukes 8. U.S.’s Panetta and South Korea’s Kim Warn Against North Korean Aggression 9. Pakistan Tests Nuclear-Capable Hatf-7 Cruise Missile 10. Libya: Stockpiles of Chemical Weapons Found 11. U.S. Has 'Nuclear Superiority' over Russia 12. Alexander Nevsky Sub to Be Put into Service in Late 2012 13. New Subs Made of Old Spare Parts 14. Successful Test Launch for Russia’s Bulava Missile 15. Topol Ballistic Missiles May Stay in Service until 2019 16. U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 17. Army Says Umatilla Depot's Chemical Weapons Mission Done 18. Iran Dangerous Now, Imagine It Nuclear 19. START Treaty: Never-Ending Story 20. The "Underground Great Wall:" An Alternative Explanation 21. What’s Down There? China’s Tunnels and Nuclear Capabilities 22. Visits Timely and Important 23. Surgical Strikes Against Key Facilities would Force Iran to Face Military Reality 24. KAHLILI: Iran Already Has Nuclear Weapons Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

EMR 12029 Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Nevsky Russia under the Mongolian yoke / Arise, you Russian people / The Battle On Ice The Field of the Dead / Alexander’s Entry Into Pskov Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester Arr.: John Glenesk Mortimer Sergeï Prokofiev EMR 12029 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + nd 1 Piccolo 2 2 Trombone + 8 Flute 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 1 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Timpani 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 1st Percussion (Xylophone / Glockenspiel / Snare Drum 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) Wood Block) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 2nd Percussion (Cymbals / Bass Drum / Triangle) 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 1 3rd Percussion (Tam-Tam / Tambourine / Suspended 2 B Tenor Saxophone Cymbal) 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) Special Parts 2 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 1st B Trombone 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 2nd B Trombone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 2 1st F & E Horn 1 B Baritone 2 2nd F & E Horn 1 E Tuba 2 3rd F & E Horn 1 B Tuba Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Cinemagic 39 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 Terminator (Fiedel) 5’34 EMR 12074 EMR 9718 2 Robocop 3 (Poledouris) 3’39 EMR 12131 EMR 9719 3 Rio Bravo (Tiomkin) 4’22 EMR 12085 EMR 9720 4 The Poseidon (Badelt) 4’02 EMR 12116 EMR 9721 5 Another Brick In The Wall (Waters) 4’14 EMR 12068 EMR 9722 6 Alexander Nevsky (Prokofiev) 9’48 EMR 12029 - 7 I’m Dreaming Of Home (Rombi) 4’38 EMR 12115 EMR 9723 8 Spartacus (Vengeance) (LoDuca) 4’13 EMR 12118 EMR 9724 9 The Crimson Pirate (Alwyn) 5’08 EMR 12041 EMR 9725 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe

Vita Mathematica 18 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Vita Mathematica Volume 18 Edited by Martin MattmullerR More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/4834 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Author Hugo Steinhaus (1887–1972) Translator Abe Shenitzer Brookline, MA, USA Editors Robert G. Burns York University Dept. Mathematics & Statistics Toronto, ON, Canada Irena Szymaniec Wrocław, Poland Aleksander Weron The Hugo Steinhaus Center Wrocław University of Technology Wrocław, Poland Vita Mathematica ISBN 978-3-319-21983-7 ISBN 978-3-319-21984-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-21984-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954183 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1.