Boris Godunov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musorgsky's Boris Godunov

22 JANUARY 2019 Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov PROFESSOR MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER Today we are going to look at what is possibly the most famous of Russian operas – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Its route to international celebrity is very clear – the great impresario Serge Diaghilev staged it in Paris in 1908, with the star bass Fyodor Chaliapin in the main role. The opera the Parisians saw would have taken Musorgsky by surprise. First, it was staged in a heavily reworked edition made by Rimsky-Korsakov after Musorgsky’s death, where only about 20% of the bars in the original were left unchanged. But that was still a modest affair compared to the steps Diaghilev took on his own initiative. The production had a Russian cast singing the opera in Russian, and Diaghilev was worried that the Parisians would lose patience with scenes that were more wordy, since they would follow none of it, so he decided simply to cut these scenes, even though this meant that some crucial turning points in the drama were lost altogether. He then reordered the remaining scenes to heighten contrasts, jumbling the chronology. In effect, the opera had become a series of striking tableaux rather than a drama with a coherent plot. But as pure spectacle, it was indeed impressive, with astonishing sets provided by the painter Golovin and with the excitement generated by Chaliapin as Boris. For all its shortcomings, it was this production that brought Musorgsky’s masterwork to the world’s attention. 1908, the year of the Paris production was nearly thirty years after Musorgsky’s death, and nearly and forty years after the opera was completed. -

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, Ed

Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, ed. Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, Madison, Milwaukee and London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968. xxiii, 391 pp. $7.50. This attractively-presented volume is yet another instance of the work of publishers in making available in a more accessible form primary sources which it was hitherto necessary to seek among dusty collections of the Hakluyt Society publications. Here we have in a single volume accounts of the travels of Richard Chancellor, Anthony Jenkinson and Thomas Randolph, together with the better-known and more extensive narrative contained in Giles Fletcher's Of the Russe Commonwealth and Sir Jerome Horsey's Travels. The most entertaining component of this volume is certainly the series of descriptions culled from George Turberville's Tragicall Tales, all written to various friends in rhyming couplets. This was apparently the sixteenth-century equivalent of the picture postcard, through apparently Turberville was not having a wonderful time! English merchants evidently enjoyed high favour at the court of Ivan IV, but Horsey's account reflects the change of policy brought about by the accession to power of Boris Godunov. Although the English travellers were very astute observers, naturally there are many inaccuracies in their accounts. Horsey, for instance, mistook the Volkhov for the Volga, and most of these good Anglicans came away from Russia with weird ideas about the Orthodox Church. The editors have, by their introductions and footnotes, provided an invaluable service. However, in the introduction to the text of Chancellor's account it is stated that his observation of the practice of debt-bondage is interesting in that "the practice of bondage by loan contract did not reach its full development until the economic collapse at the end of the century and the civil wars that followed". -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:40 PM - 4:00 PM Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J. Taylor Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons Taylor, Joshua J., "Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 4. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/4 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century What does it mean to be Russian? In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian nobility was engrossed with French culture. According to Dr. Marina Soraka and Dr. Charles Ruud, “Russian nobility [had a] weakness for the fruits of French civilization.”1 When Peter the Great came into power in 1682-1725, he forced Western ideals and culture into the very way of life of the aristocracy. “He wanted to Westernize and modernize all of the Russian government, society, life, and culture… .Countries of the West served as the emperor’s model; but the Russian ruler also tried to adapt a variety of Western institutions to Russian needs and possibilities.”2 However, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in 1812, he threw the pro- French aristocracy in Russia into an identity crisis. -

Boris Godunov

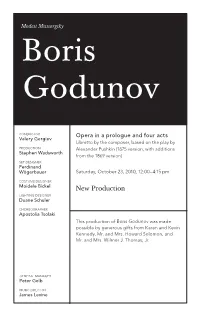

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

The World of Child Psychology in Early Mussorgsky's Works

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 10, NO. 4, 3436-3449 OPEN ACCESS The World of Child Psychology in Early Mussorgsky’s Works Iza A. Nemirovskayaa, Lyudmila S. Bakshia, Olga V. Gromovaa, Irina A. Korsakovaa, and Alexander S. Bazikovb aMoscow state Institute of music named after A. G Schnitke, Moscow, RUSSIA; bGnessin Russian Academy of Music, Moscow, RUSSIA ABSTRACT The world of a child as a topic gave birth to a number of Mussorgsky`s decisions concerning figurative modes, music style systems, principles of composition and music poetics. The master captured the microcosm of passions, that originally inhabit the soul of a child, and his works presented an embodiment of the deep, ontological nature of any human personality with its typical mixture of good and evil. In his musical works about children the composer also showed us some fundamental laws of psychology: some child entertainments, that are not quite harmless, conceal future repulsive character traits of an adult; and evident aggressiveness of a person is often a result of a former child having been unjustly insulted. All this makes it possible for us to speak of Mussorgsky as a composer and a child psychologist. KEYWORDS ARTICLE HISTORY Mussorgsky, childhood, psychology, poetics Received 3 May 2016 Revised 13 July 2016 Accepted 22 July 2016 Introduction The interest of Mussorgsky to the world of a child was intrinsic to his soul capable of understanding children and evoking their love in response. Lonely in his soul, he had a trusting heart, openness and sincerity that are characteristic to children. A.N. -

Understanding the Cultural and Nationalistic Impacts of the Moguchaya Kuchka

Musical Offerings Volume 10 Number 2 Fall 2019 Article 1 10-7-2019 Understanding the Cultural and Nationalistic Impacts of the moguchaya kuchka Austin M. Doub Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Russian Literature Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Doub, Austin M. (2019) "Understanding the Cultural and Nationalistic Impacts of the moguchaya kuchka," Musical Offerings: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2019.10.2.1 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol10/iss2/1 Understanding the Cultural and Nationalistic Impacts of the moguchaya kuchka Document Type Article Abstract This paper explores Russian culture beginning in the mid nineteenth-century as the leading group of composers and musicians known as the moguchaya kuchka, or The Mighty Five, sought to influence Russian culture and develop a "pure" school of Russian music amid rampant westernization. Comprised of César Cui, Alexander Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, this group of inspired musicians opposed westernization and supported Official Nationalismy b the incorporation of folklore, local village traditions, and promotion of their Tsar as a supreme political leader. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

Reuven Tsur the End of Boris

Reuven Tsur The End of Boris Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation Closure and the Grotesque In this article I will consider the effects of two alternative endings of Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godounov, and the possible interactions of these endings with a solemn and a grotesque quality, respectively.1 An early version (1869) ends with the scene of Boris’ death. Mussorgsky later revised this version (1874) adding, among other things, a final scene in the Kromy Forest, shifting the focus away from Boris and giving the opera a powerful new shape. In this scene we witness a mob of vagabonds who get hold of one of Boris’ boyars, deride him and threaten to tear him into pieces. They perform such mock- rituals as a mock-coronation, and a mock-wedding with the oldest woman in the mob. After Mussorgsky’s death, Rimsky-Korsakov re-orchestrated and revised Boris Godunov “in a heroic endeavour to make the opera more audience-friendly”. Among other changes, Rimsky-Korsakov reversed the order of the last two scenes, ending the opera, again, with Boris’ death. For nearly a century, only Rimsky-Korsakov’s version was performed, Mussorgsky’s version was even lost, and only recently rediscovered by David Lloyd-Jones. Why is one ending more “audience-friendly” than the other? And why do some of our contemporaries (musicians and audiences), and apparently Mussorgsky himself prefer precisely the ending that is supposed to be less “audience-friendly”? The last two scenes, the death scene and the Kromy Forest scene, display opposite stylistic modes. The former is in the high-mimetic, the latter in the low-mimetic mode. -

GURPS Classic Russia

RUSSIA Empire. Enigma. Epic. By S. John Ross Additional Material by Romas Buivydas, Graeme Davis, Steffan O'Sullivan and Brian J. Underhill Edited by Spike Y Jones and Susan Pinsonneault, with Mike Hurst Cover by Gene Seabolt, based on a concept by S. John Ross Illustrated by Heather Bruton, Eric Hotz and Ramón Perez GURPS System Design by Steve Jackson Scott Haring, Managing Editor Page Layout and Typography by Amy J. Valleau Graphic Design and Production by Carol M. Burrell and Gene Seabolt Production Assistance by David Hanshaw Print Buying by Monica Stephens Art Direction by Carol M. Burrell Woody Eblom, Sales Manager Playtesters: Captain Button, Graeme Davis, Kenneth Hite, Dean Kimes, Marshall Ryan Maresca, Michael Rake Special Thanks to: Tim Driscoll, for laughing at the good bits; Scott Maykrantz, for bringing "opinionated" to the level of art; Dan Smith, for his encouragement and unique good humor; Moose Jasman, for studying Russian history at just the right time; and to Ivan Grozny, for being such a criminally insane, despotic villain — every book needs one. This book is dedicated to the memory of Reader's Haven, the finest bookshop ever to go out of business in Havelock, North Carolina, and to the garners there, for "putting the quarter into John." GURPS and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. GURPS Russia, Pyramid and Illuminati Online and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. GURPS Russia is copyright © 1998 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated.