Reuven Tsur the End of Boris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, Ed

Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, ed. Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, Madison, Milwaukee and London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968. xxiii, 391 pp. $7.50. This attractively-presented volume is yet another instance of the work of publishers in making available in a more accessible form primary sources which it was hitherto necessary to seek among dusty collections of the Hakluyt Society publications. Here we have in a single volume accounts of the travels of Richard Chancellor, Anthony Jenkinson and Thomas Randolph, together with the better-known and more extensive narrative contained in Giles Fletcher's Of the Russe Commonwealth and Sir Jerome Horsey's Travels. The most entertaining component of this volume is certainly the series of descriptions culled from George Turberville's Tragicall Tales, all written to various friends in rhyming couplets. This was apparently the sixteenth-century equivalent of the picture postcard, through apparently Turberville was not having a wonderful time! English merchants evidently enjoyed high favour at the court of Ivan IV, but Horsey's account reflects the change of policy brought about by the accession to power of Boris Godunov. Although the English travellers were very astute observers, naturally there are many inaccuracies in their accounts. Horsey, for instance, mistook the Volkhov for the Volga, and most of these good Anglicans came away from Russia with weird ideas about the Orthodox Church. The editors have, by their introductions and footnotes, provided an invaluable service. However, in the introduction to the text of Chancellor's account it is stated that his observation of the practice of debt-bondage is interesting in that "the practice of bondage by loan contract did not reach its full development until the economic collapse at the end of the century and the civil wars that followed". -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Boris Godunov

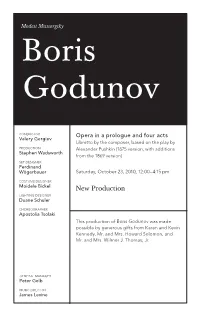

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

GURPS Classic Russia

RUSSIA Empire. Enigma. Epic. By S. John Ross Additional Material by Romas Buivydas, Graeme Davis, Steffan O'Sullivan and Brian J. Underhill Edited by Spike Y Jones and Susan Pinsonneault, with Mike Hurst Cover by Gene Seabolt, based on a concept by S. John Ross Illustrated by Heather Bruton, Eric Hotz and Ramón Perez GURPS System Design by Steve Jackson Scott Haring, Managing Editor Page Layout and Typography by Amy J. Valleau Graphic Design and Production by Carol M. Burrell and Gene Seabolt Production Assistance by David Hanshaw Print Buying by Monica Stephens Art Direction by Carol M. Burrell Woody Eblom, Sales Manager Playtesters: Captain Button, Graeme Davis, Kenneth Hite, Dean Kimes, Marshall Ryan Maresca, Michael Rake Special Thanks to: Tim Driscoll, for laughing at the good bits; Scott Maykrantz, for bringing "opinionated" to the level of art; Dan Smith, for his encouragement and unique good humor; Moose Jasman, for studying Russian history at just the right time; and to Ivan Grozny, for being such a criminally insane, despotic villain — every book needs one. This book is dedicated to the memory of Reader's Haven, the finest bookshop ever to go out of business in Havelock, North Carolina, and to the garners there, for "putting the quarter into John." GURPS and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. GURPS Russia, Pyramid and Illuminati Online and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. GURPS Russia is copyright © 1998 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. -

1 Sergei M. Eisenstein: Alexander Nevsky (1937/8) and Ivan The

1 Sergei M. Eisenstein: Alexander Nevsky (1937/8) and Ivan the Terrible Parts I and II (1942-5) The history and politics of these films are imbecile. Take the opening of Ivan I: Ivan is crowned, despite the mutterings of the ambassadors, of the boyars, and of ugly old Efrosinia, whose idiot son (he talks with his mouth full) is now debarred the succession. Noble, clean-cut sixteenth-century proletarians gatecrash the coronation, and are abashed by Ivan’s majesty. Cruel, foolish Tartar envoys from Khazan gatecrash the coronation too, and threaten Muscovy with “Moskva – malenky: Khazan – bolshoi!” They give Ivan their equivalent of Henry V’s tennis balls: a dagger with which to kill himself. He treats the gesture with apt contempt, and says that although he has never wanted war, if they want it they can have it. The noble, clean-cut proletarians cheer him, saying with delight, “The Tsar is no fool!” and one eyeballs the chief of the cruel, foolish Khazan envoys with, “Khazan – malenky: Moskva – bolshoi!” whereupon the Khazan envoy looks terribly worried … and so on. The acting is totalitarian; as if Stanislavsky had never been. Behaviouristic it isn’t, and total identification with your part is a long way off – it’s all nineteenth-century ham, in close- up – solid, semaphore acting. And not a raised eyebrow nor a rolling eye is there without 2 Eisenstein’s say-so. Few shots last more than five seconds; the rhythm is dictated, not by the actors’ instincts, but by the director’s will. Actors are not creative artists, but puppets – filmed preferably in close-up, lit from below. -

BORIS GODUNOV Modest Mussorgsky Prologue: at the Instigation of the Boyars, Headed by Shuisky, Russian Peasants Are Forced by P

BORIS GODUNOV Modest Mussorgsky Prologue: At the instigation of the Boyars, headed by Shuisky, Russian peasants are forced by police into demonstrating for Boris Godunov's ascension to the vacant throne of Russia. Shchelkalov, Secretary of the Duma (Council of Boyars), appears at the monastery doorway to announce that Boris still refuses and that Russia is doomed. A procession of pilgrims passes, praying to God for help. Amidst cheering crowds, the great bells of Moscow herald the coronation of Boris. As the procession leaves the cathedral, Boris appears in triumph. Haunted by a strange foreboding, he prays for God's blessing. Addressing his people, he invites them all to the feast, as the crowd resumes rejoicing. ACT I: The old monk Pimen is finishing a history of Russia. Young Grigory, a novice, awakes and describes to Pimen his nightmare in which he climbed a lofty tower and viewed the swarming multitude of Muscovites below who mocked him until he stumbled and fell. Pimen tells Grigory that fasting and prayer bring peace of mind, and compares the quiet solitude of the cloister to the outside world of sin and idle pleasure. Grigory questions Pimen about the dead Tsarevich Dimitri, legal heir to the Russian throne; Pimen recounts how Boris ordered the boy's murder. Left alone, Grigory condemns Boris and his crime and decides to leave the cloister. Three guests interrupt the innkeeper's ballad: two drunken monks-Varlaam and Missail-and the disguised Grigory, who is being pursued by the police for escaping from the monastery. Now considering it his mission to expose Boris, Grigory is attempting flight to Lithuania, where he will assemble forces and, proclaiming himself the Tsarevich Dimitri, claim the Russian throne. -

Ivan the Terrible Is Trying to Make Amends for All the Wrongs He Has Done in His Life

I'M SORRY 0. I'M SORRY - Story Preface 1. BEGGAR IN THE PALACE 2. THE FIRST TSAR 3. THE GOOD REIGN 4. DEATH BY POISON 5. ARCHITECTS BLINDED 6. ART AT THE TIME OF IVAN IV 7. THE BAD REIGN 8. LEGACY and MURDER 9. OLD BEFORE HIS TIME 10. I'M SORRY In this painting, by Klavdiy Lebedev (1852-1916), an aging Ivan the Terrible is trying to make amends for all the wrongs he has done in his life. He is asking the Father Superior, of Pskovo-Pechorsky Monastery, to permit him to take tonsure (shave the hair from his scalp in monkish fashion) at the monastery. Image online, courtesy Web Gallery of Art. PD Near the end of his life, wanting to find forgiveness, Ivan - it is said - dramatically changed his attitude and behavior. He was obsessed with sorrow and guilt for all he had done, including killing his son. Praying for those he had executed, he forgave them of whatever supposed crime they had committed. He also paid for prayers to be said for the souls of the murdered. The Tsar was re-christened as a monk, taking the name of "Jonah," perhaps out of respect for the man (St. Jonah) who founded the Pskov-Caves Monastery (Russia's oldest-in-existence) which Ivan had visited. Death for the fearsome ruler came at age 54. Setting up a chess board on his bed, for a match (it is said) with his friend Boris Godunov, he died quietly and naturally inside the Kremlin’s walls. He was interred (reportedly wearing the clothes of a monk instead of an emperor) in the Archangel Cathedral where other Russian royals, who lived before and after him, have also been laid to rest. -

NOBODY's FOOL: a STUDY of the YRODIVY in BORIS GODUNOV Carol J. Pollard, B.M.E Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF

NOBODY’S FOOL: A STUDY OF THE YRODIVY IN BORIS GODUNOV Carol J. Pollard, B.M.E Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 1999 APPROVED: Lester Brothers, Major Professor and Chair Henry L. Eaton, Minor Professor J. Michael Cooper, Committee Member Will May, Interim Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate. Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Pollard, Carol J., Nobody’s Fool: A Study of the Yrodivy in Boris Godunov. Master of Arts (Musicology), December 1999, 69 pp., 2 figures, 2 musical examples, references, 39 titles, 5 scores. Modest Musorgsky completed two versions of his opera Boris Godunov between 1869 and 1874, with significant changes in the second version. The second version adds a concluding lament by the fool character that serves as a warning to the people of Russia beyond the scope of the opera. The use of a fool is significant in Russian history and this connection is made between the opera and other arts of nineteenth-century Russia. These changes are, musically, rather small, but historically and socially, significant. The importance of the people as a functioning character in the opera has precedence in art and literature in Russia in the second half of the nineteenth-century and is related to the Populist movement. Most importantly, the change in endings between the two versions alters the entire meaning of the composition. This study suggests that this is a political statement on the part of the composer. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . -

Two Capitals

Your Moscow Introductory Tour: Specially designed for our cruise passengers that have 3 port days in Saint Petersburg, this tour offers an excellent and thorough introduction to the fascinating architectural, political and social history of Moscow. Including the main highlights of Moscow, your tour will begin with an early morning transfer from your ship to the train station in St. Peterburg where you will board the high speed (Sapsan) train to Moscow. Panoramic City Tour Upon reaching Moscow, you will be met by your guide and embark on a city highlights drive tour (with photo stops). You will travel to Vorobyevi Hills where you will be treated to stunning panoramic views overlooking Moscow. Among other sights, this tour takes in the city's major and most famous sights including, but not limited to: Vorobyevi (Sparrow) Hills; Moscow State University; Novodevichiy Convent; the Diplomatic Village; Victory Park; the Triumphal Arch; Kutuzovsky Prospect, and the Arbat. Kutuzovsky Prospect; Moscow State University; Triumphal Arch; Russian White House; Victory Park; the Arbat Sparrow Hills (Vorobyovy Gory), known as Lenin Hills and named after the village Vorobyovo, is a famous Moscow park, located on one of the so called "Seven hills of Moscow". It’s a green hill on the bank of the Moskva river, huge beautiful park, pedestrian embankment, river station, and an observation platform which gives the best panorama of the city, Moskva River, and a view of Moscow State University. The panoramic view shows not only some magnificent buildings, but also common dwelling houses (known as "boxes"), so typical of any Russian town. -

Introduction to the History of Russia (Ix-Xviii Century)

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education Lobachevsky State University of Nizhni Novgorod National Research University K.V. Kemaev INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF RUSSIA (IX-XVIII CENTURY) TUTORIAL Nizhni Novgorod 2017 МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ Федеральное государственное автономное образовательное учреждение высшего образования «Национальный исследовательский Нижегородский государственный университет им. Н.И. Лобачевского» К.В. Кемаев ВВЕДЕНИЕ В КУРС ПО ИСТОРИИ РОССИИ (IX-XVIII ВЕКА) Учебно-методическое пособие по дисциплине «История» Рекомендовано методической комиссией Института экономики и предпринимательства ННГУ для иностранных студентов, обучающихся по направлению подготовки 38.03.01 «Экономика» (бакалавриат) на английском языке Нижний Новгород 2017 2 УДК 94 ББК 63.3 К-35 К-35 К.В. Кемаев. Введение в курс по истории России (IX-XVIII века): Учебно-методическое пособие. – Нижний Новгород: Нижегородский госуниверситет, 2017. − 81 с. Рецензент: к.э.н., доцент Ю.А.Гриневич В настоящем пособии изложены учебно-методические материалы по курсу «История» для иностранных студентов, обучающихся в ННГУ по направлению подготовки 38.03.01 «Экономика» (бакалавриат). Пособие дает возможность бакалаврам расширить основные знания о истории, овладевать умением комплексно подходить к вопросам развития, использовать различные источники информации; развивать экономическое мышление Ответственный за выпуск: председатель методической комиссии ИЭП ННГУ, к.э.н., доцент Летягина Е.Н. УДК 94 ББК 63.3 К.В.Кемаев Нижегородский государственный университет им. Н.И. Лобачевского, 2017 3 2 CONTENTS Course Agenda 3 Session 1. Russian lands before 862 AD 4 Session 2. First Rurikids and foundation of the Rus’ of Kiev 7 8 Session 3. Decline & political fragmentation of the Rus’ of Kiev 11 Session 4.