Ivan the Terrible Is Trying to Make Amends for All the Wrongs He Has Done in His Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: the Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator

1 History Is Made in the Dark 4: Alexander Nevsky: The Prince, the Filmmaker and the Dictator In May 1937, Sergei Eisenstein was offered the opportunity to make a feature film on one of two figures from Russian history, the folk hero Ivan Susanin (d. 1613) or the mediaeval ruler Alexander Nevsky (1220-1263). He opted for Nevsky. Permission for Eisenstein to proceed with the new project ultimately came from within the Kremlin, with the support of Joseph Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator was something of a cinephile, and he often intervened in Soviet film affairs. This high-level authorisation meant that the USSR’s most renowned filmmaker would have the opportunity to complete his first feature in some eight years, if he could get it through Stalinist Russia’s censorship apparatus. For his part, Eisenstein was prepared to retreat into history for his newest film topic. Movies on contemporary affairs often fell victim to Soviet censors, as Eisenstein had learned all too well a few months earlier when his collectivisation film, Bezhin Meadow (1937), was banned. But because relatively little was known about Nevsky’s life, Eisenstein told a colleague: “Nobody can 1 2 find fault with me. Whatever I do, the historians and the so-called ‘consultants’ [i.e. censors] won’t be able to argue with me”.i What was known about Alexander Nevsky was a mixture of history and legend, but the historical memory that was most relevant to the modern situation was Alexander’s legacy as a diplomat and military leader, defending a key western sector of mediaeval Russia from foreign foes. -

Early Russia

Early Russia Timeline Cards Subject Matter Expert Chapter 1, Card 5 The Christening of Grand Duke Vladimir (c.956–1015), 1885–96 (mural), Vasnetsov, Victor Mikhailovich (1848–1926) / Vladimir Matthew M. Davis, PhD, University of Virginia Cathedral, Kiev, Ukraine / Bridgeman Images Illustration and Photo Credits Chapter 2, Card 1 Russia: Sacking of Suzdal by Batu Khan in February, 1238. Mongol Title Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Ivan the Terrible 1530–1584) Tsar of Russia from 1533, leading Invasion of Russia. A miniature from the 16th century chronicle of his army at the Siege of Kazan in August 1552, 1850 / Universal History Archive/UIG / Suzdal / Pictures from History / Bridgeman Images Bridgeman Images Chapter 2, Card 2 Portrait of Marco Polo (1254–1324), by Dolfino / Biblioteca Nazionale, Chapter 1, Card 1 Jacob Wyatt Turin, Italy / Bridgeman Images Chapter 1, Card 2 Exterior view of Haghia Sophia, built 532–37 AD/Istanbul, Turkey/ Chapter 2, Card 3 Battle between the Russian and Tatar troops in 1380, 1640s (oil on Bildarchiv Steffens/Bridgeman Images canvas), Russian School, (17th century) / Art Museum of Yaroslavl, Chapter 1, Card 4 The Conversion of Olga (d.969) from the Madrid Skylitzes (vellum), Russia / Bridgeman Images Byzantine School, (12th century) / Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, Spain / Chapter 3 Tsar Ivan III (1440–1505) Tearing the Deed of Tatar Khan, 1862 (oil Bridgeman Images on canvas), Shustov, Nikolai Semenovich (c.1838–69) / Sumy Art Museum, Sumy, Ukraine / Bridgeman Images Creative Commons Licensing Chapter 4 Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Ivan the Terrible 1530–1584) Tsar of Russia from This work is licensed under a 1533, leading his army at the Siege of Kazan in August 1552, 1850 / Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Universal History Archive/UIG / Bridgeman Images 4.0 International License. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

01 5 Faces of Russia

The Faces of Russia Grade Level: Fifth Grade Presented by: Teresa Beazley, Hardy Oak Elementary School, San Antonio, TX Laura Eberle, Hardy Oak Elementary, San Antonio, TX Length of Unit: 2 weeks (9 lessons) I. ABSTRACT This is a unit written for fifth grade on the early growth and expansion of Russia, from the time of Ivan the Great to Catherine the Great. It covers in detail the topics outlined in the world civilization strand of the Core Knowledge Sequence, as well as the related geography topics. Students will look at the many faces of Russia to understand how her history has been shaped by the geography of the region, the cultures that influenced her beginning, and the strong leadership of the early czars. The unit is comprised of nine lessons that are designed to be covered in a two-week period. II. OVERVIEW A. Concept Objectives 1. Understand how geography influences the development of a country. 2. Understand how political systems gain and exercise power over people and land. 3. Appreciate how cultures honor their heritage through their arts, architecture, literature and symbols B. Content covered from Core Knowledge Sequence 1. Russia as the successor to Byzantine Empire 2. Moscow as the new center of Eastern Orthodox Church and Byzantine culture 3. Ivan III (The Great); “czar” 4. Ivan IV (The Terrible) 5. Peter the Great: modernizing and “Westernizing” Russia 6. Catherine the Great 7. Geography of Russia a. Moscow and St. Petersburg b. Ural Mountains, Siberia, steppes c. Volga and Don Rivers d. Black, Caspian, and Baltic Seas e. -

Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, Ed

Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, ed. Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, Madison, Milwaukee and London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968. xxiii, 391 pp. $7.50. This attractively-presented volume is yet another instance of the work of publishers in making available in a more accessible form primary sources which it was hitherto necessary to seek among dusty collections of the Hakluyt Society publications. Here we have in a single volume accounts of the travels of Richard Chancellor, Anthony Jenkinson and Thomas Randolph, together with the better-known and more extensive narrative contained in Giles Fletcher's Of the Russe Commonwealth and Sir Jerome Horsey's Travels. The most entertaining component of this volume is certainly the series of descriptions culled from George Turberville's Tragicall Tales, all written to various friends in rhyming couplets. This was apparently the sixteenth-century equivalent of the picture postcard, through apparently Turberville was not having a wonderful time! English merchants evidently enjoyed high favour at the court of Ivan IV, but Horsey's account reflects the change of policy brought about by the accession to power of Boris Godunov. Although the English travellers were very astute observers, naturally there are many inaccuracies in their accounts. Horsey, for instance, mistook the Volkhov for the Volga, and most of these good Anglicans came away from Russia with weird ideas about the Orthodox Church. The editors have, by their introductions and footnotes, provided an invaluable service. However, in the introduction to the text of Chancellor's account it is stated that his observation of the practice of debt-bondage is interesting in that "the practice of bondage by loan contract did not reach its full development until the economic collapse at the end of the century and the civil wars that followed". -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Eisenstein's "Ivan the Terrible, Part II" As Cultural Artifact Beverly Blois

Eisenstein's "Ivan The Terrible, Part II" as Cultural Artifact Beverly Blois In one of the most famous Russian paintings, Ilya Repin's "Ivan the Terrible with his murdered son," an unkempt and wild-eyed tsar clutches his expiring son, from whose forehead blood pours forth. Lying beside the two men is a large staff with which, moments earlier, Ivan had in a fit of rage struck his heir-apparent a mortal blow. This was a poignant, in fact tragic, moment in the history of Russia because from this event of the year 1581, a line of rulers stretching back to the ninth century effectively came to an end, ushering in a few years later the smutnoe vermia ("time of trouble") the only social crisis in Russian history that bears comparison with the revolution of 1917. Contemporary Russians tell an anekdot about this painting in which an Intourist guide, leading a group of Westerners rapidly through the rooms of the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow, comes to Repin's canvas, and wishing, as always, to put the best face on things, says, "And here we have famous painting, Ivan the Terrible giving first aid to his son." The terribilita of the sixteenth century tsar had been modernized to fit the needs of the mid-twentieth century. Ivan had been reinterpreted. In a similar, but not so trifling way, Sergei Eisenstein was expected to translate the outlines of Ivan's accomplishments into the modern language of socialist realism when he was commissioned to produce his Ivan films in 1941. While part one of his film, released in 1945, won the Stalin Prize, First Class, part two, which was very dose to release in 1946, was instead withheld. -

History of Russia to 1855 Monday / Wednesday / Friday 3:30-4:30 Old Main 002 Instructor: Dr

HIST 294-04 Fall 2015 History of Russia to 1855 Monday / Wednesday / Friday 3:30-4:30 Old Main 002 Instructor: Dr. Julia Fein E-mail: j [email protected] Office: Old Main 300, x6665 Office hours: Open drop-in on Thursdays, 1-3, and by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION Dear historians, Welcome to the first millennium of Russian history! We have a lively semester in front of us, full of famous, infamous, and utterly unknown people: from Ivan the Terrible, to Catherine the Great, to the serfs of Petrovskoe estate in the 19th century. Most of our readings will be primary documents from medieval, early modern, and 19th-century Russian history, supplemented with scholarly articles and book sections to provoke discussion about the diversity of possible narratives to be told about Russian history—or any history. We will also examine accounts of archaeological digs, historical maps, visual portrayals of Russia’s non-Slavic populations, coins from the 16th and 17th centuries, and lots of painting and music. As you can tell from our Moodle site, we will be encountering a lot of Russian art that was made after the period with which this course concludes. Isn’t this anachronistic? One of our course objectives deals with constructions of Russian history within R ussian history. We will discuss this issue most explicitly when reading Vasily Kliuchevsky on Peter the Great’s early life, and the first 1 HIST 294-04 Fall 2015 part of Nikolai Karamzin’s M emoir , but looking at 19th- and 20th-century artistic portrayals of medieval and early modern Russian history throughout also allows us to conclude the course with the question: why are painters and composers between 1856 and 1917 so intensely interested in particular moments of Russia’s past? What are the meanings of medieval and early modern Russian history to Russians in the 19th and 20th centuries? The second part of this course sequence—Revolutionary Russia and the Soviet Union—picks up this thread in spring semester. -

Boris Godunov

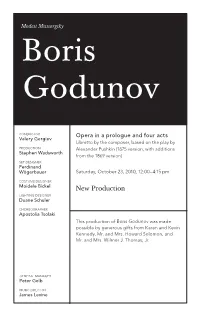

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

A New Perspective in Russian Intellectual History: Russian Political Thought in Early Modern Times

Вивлioѳика: E-Journal of Eighteenth-Century Russian Studies, Vol. 7 (2019): 119-123 119 __________________________________________________________________________________ A New Perspective in Russian Intellectual History: Russian Political Thought in Early Modern Times Derek Offord The University of Bristol [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ G. M. Hamburg, Russia’s Path Toward Enlightenment: Faith, Politics, and Reason, 1500– 1801. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016, 912 p. ISBN: 9780300113136 ___________________________________________________________________________ Gary Hamburg’s erudite and thoughtful survey of early modern Russian thought began its life as part of a more general study of Russian thought up until the revolutions of 1917. As originally conceived, this study would have built upon the author’s already substantial corpus of work on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russian history and thought, most notably his monograph of 1992 on Boris Chicherin and his volume of 2010, co-edited with Randall A. Poole, on freedom and dignity in Russian philosophy from 1830 to 1930. As work progressed, however, it became clear that thinkers active from the early sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth demanded more attention than Hamburg had anticipated; in fact, they came to merit a book all to themselves. The resulting 900-page product of his reflection on the prehistory of modern Russian thought enables him to straddle what are generally perceived as two great divides: First, the supposed divide between Muscovite and Imperial Russia and, second, that between the traditional religious and the secular enlightened forms of Russian culture. The enormous volume of material that Hamburg presents in this monograph is organized in three parts within a broadly chronological framework. -

Reuven Tsur the End of Boris

Reuven Tsur The End of Boris Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation Closure and the Grotesque In this article I will consider the effects of two alternative endings of Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godounov, and the possible interactions of these endings with a solemn and a grotesque quality, respectively.1 An early version (1869) ends with the scene of Boris’ death. Mussorgsky later revised this version (1874) adding, among other things, a final scene in the Kromy Forest, shifting the focus away from Boris and giving the opera a powerful new shape. In this scene we witness a mob of vagabonds who get hold of one of Boris’ boyars, deride him and threaten to tear him into pieces. They perform such mock- rituals as a mock-coronation, and a mock-wedding with the oldest woman in the mob. After Mussorgsky’s death, Rimsky-Korsakov re-orchestrated and revised Boris Godunov “in a heroic endeavour to make the opera more audience-friendly”. Among other changes, Rimsky-Korsakov reversed the order of the last two scenes, ending the opera, again, with Boris’ death. For nearly a century, only Rimsky-Korsakov’s version was performed, Mussorgsky’s version was even lost, and only recently rediscovered by David Lloyd-Jones. Why is one ending more “audience-friendly” than the other? And why do some of our contemporaries (musicians and audiences), and apparently Mussorgsky himself prefer precisely the ending that is supposed to be less “audience-friendly”? The last two scenes, the death scene and the Kromy Forest scene, display opposite stylistic modes. The former is in the high-mimetic, the latter in the low-mimetic mode.