Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

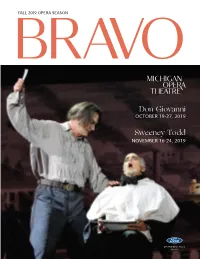

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

The Treasure of Generosity South Bay to Educate the Community and Foster the Spirit of Dana—A Spirit That Recognizes and Manifests the Interdependent Nature of Being

The Treasure of Generosity This booklet has been published by Insight Meditation The Treasure of Generosity South Bay to educate the community and foster the spirit of dana—a spirit that recognizes and manifests the interdependent nature of being. The primary “If people knew, as I know, the results of giving and intent of this booklet is to encourage the cultivation sharing, they would not eat a meal without sharing it, and practice of dana. IMSB, like most religious and nor would they allow the taint of stinginess or meanness charitable organizations, depends upon donations to to overtake their minds.” sustain its operations. We encourage you to experience —The Buddha, Ittivutakkha 26 the treasures of generosity by giving in ways that retain Generosity is commonly defined as the act of freely the spirit of dana. giving or sharing what we have. The giving of money and material objects, the sharing of time, effort, and presence, and the sharing of teachings all are expressions of generosity. Generosity is at the heart of the Buddha’s teachings. In Buddhist traditions, the act of generosity is called dana, in the ancient Pali language. The inner disposition toward being generous is the less well-known Pali term, caga. The underlying spirit of dana, which began as townspeople offered support to monks and nuns on alms rounds, carries on to this day. Today, our own spiritual practices provide us with the opportunity to explore the rich relationship between dana and caga while pointing us toward a healthy manifestation of non-attachment, non-aversion, and interdependence. -

Tzedakah As the Defining Social Marker of Jewish Identity

Tzedakah as the Defining Social Marker of Jewish Identity A. The Test of a True Jew: Check the Pocketbook B. Maimonides: Appealing to Jewish Genes – The Perfect “Pitch” “[God] has told you, human being, what is good and what Adonai requires of you: Nothing but to do justice (mishpat), to love kindness (hesed), and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8) הִ גִיד לְָך ָאדָ ם מַ ה-ּטוֹב ּומָ ה-יְהוָה ּדוֹרֵ ׁש מִמְ ָך כִ י אִ ם- עֲׂשוֹתמִׁשְ טפָ וְַאהֲבַת חֶסֶ ד וְהַצְ נֵעַ לֶכֶת עִ ם- אֱֹלהֶ יָך. Noam Zion, Hartman Institute, [email protected] – excerpted form from Jewish Giving in Comparative Perspectives: History and Story, Law and Theology, Anthropology and Psychology. Book One: From Each According to One’s Ability: Duties to Poor People from the Bible to the Welfare State and Tikkun Olam Previous Books: A DIFFERENT NIGHT: The Family Participation Haggadah By Noam Zion and David Dishon LEADER'S GUIDE to "A DIFFERENT NIGHT" By Noam Zion and David Dishon A DIFFERENT LIGHT: Hanukkah Seder and Anthology including Profiles in Contemporary Jewish Courage By Noam Zion A Day Apart: Shabbat at Home By Noam Zion and Shawn Fields-Meyer A Night to Remember: Haggadah of Contemporary Voices Mishael and Noam Zion www.haggadahsrus.com 1 Our teachers have said: "If all troubles were assembled on one side and poverty on the other, poverty would outweigh them all." - Midrash Shemot Rabbah 31:14 "The sea of a mighty population, held in galling fetters, heaves uneasily in the tenements.... The gap between the classes in which it surges, unseen, unsuspected by the thoughtless, is widening day by day. -

Islamic Charity) for Psychological Well-Being

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 2, 2020 Review Article UNDERSTANDING OF SIGNIFICANCE OF ZAKAT (ISLAMIC CHARITY) FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING 1Mohd Nasir Masroom, 2Wan Mohd Azam Wan Mohd Yunus, 3Miftachul Huda 1Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 2Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 3Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Malaysia Received: 25.11.2019 Revised: 05.12.2019 Accepted: 15.01.2020 Abstract The act of worship in Islam is a form of submission and a Muslim’s manifestation of servitude to Allah SWT. Yet, it also offers certain rewards and benefits to human psychology. The purpose of this article is to explain how Zakat (Islamic charity), or the giving of alms to the poor or those in need, can help improve one’s psychological well-being. The study found that sincerity and understanding the wisdom of Zakat are the two important elements for improving psychological well-being among Muslim believers. This is because Zakat can foster many positive attitudes such sincerity, compassion, and gratitude. Moreover, Zakat can also prevent negative traits like greed, arrogance, and selfishness. Therefore, Zakat, performed with sincerity and philosophical understanding can be used as a form treatment for neurosis patients. It is hoped that this article can serve as a guideline for psychologists and counsellors in how to treat Muslim neurosis patients. Keywords: Zakat; Psychological Well-being; Muslim; Neurosis Patient © 2019 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.02.127 INTRODUCTION Zakat (Islamic charity) is one of the five pillars of Islam, made THE DEFINITION OF ZAKAT, PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING compulsory for each Muslim to contribute part of their assets AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTURBANCE or property to the rightful and qualified recipients. -

Download Download

J OURNAL OF MUSLIM PHILANTHROPY & CIVIL SOCIETY 38 BOOK REVIEW GIVING TO GOD: ISLAMIC CHARITY IN REVOLUTIONARY TIMES Mittermaier, A. (2019). Giving to God: Islamic Charity in Revolutionary Times. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN: 978-0520300835. 0F Reviewed by Zeeshan Noor The University of Texas at Dallas Amira Mittermaier’s book, Giving to God: Islamic Charity in Revolutionary Times, examines Islamic charity in Egypt over eight years, beginning in 2011. Mittermaier volunteered at charity organizations, Sufi khidmas (soup kitchens), Ramadan tables, and Muslim shrines. The book consists of four sections: the preface, an introductory chapter, a major section on the giving of charity, and a final section on the receipt of charity. The preface provides a transliteration guide and discusses Mittermaier’s methodology. It also relates her experience shadowing Madame Salwa, who provides food for the poor. Salwa does so as a religious duty, although she told Mittermaier she doesn’t care for the poor. Mittermaier, as a secular Westerner, engages in charity for humanitarian reasons. The introductory chapter, “Revolutions Don’t Stop Charity,” begins with the 2011 revolution in Egypt. Mittermaier watched the revolution from Germany and arrived in Cairo four months later. She discusses the Muslim Brotherhood, the NGO from which Mubarak’s successor, Mohamed Morsi, emerged. She explains how the detention of Morsi not only led to a crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, but other NGOs as well. In this chapter she quotes activists, self-proclaimed revolutionaries, friends, and others—specifically their views on the poor Copyright © 2019 Zeeshan Noor http://scholarworks.iu.edu/iupjournals/index.php/jmp DOI: 10.2979/muslphilcivisoc.3.1.04 Volume III • Number I • 2019 J OURNAL OF MUSLIM PHILANTHROPY & CIVIL SOCIETY 39 and charity. -

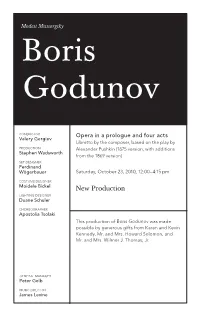

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Treasures of the Church Prayer Service

2020-2021 Treasures of the Church Prayer Service Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist March 16, 2021 CATHOLIC CHARITIES Inspired by Christ’s call to serve, our mission is to provide service to those in need, to advocate for justice and to call upon others to do the same. OUR PROGRAMS: Adoption Outreach & Case Management Adult Day Services Pregnancy & Parenting Support Behavioral Health Refugee & Immigration Services In Home Support/ Supported Parenting Hoarding Intervention Since 1920, we have adapted to meet the changing needs of people impacted by poverty in our communities. 2 TREASURES OF THE CHURCH AWARDS Catholic Charities is excited to honor Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki’s 2020 Treasures of the Church Award recipients this Lent 2021 at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. The honorees are community leaders, dedicated volunteers, loyal friends, and compassionate neighbors. From advocating for those without a voice, improving the well-being of families through mentorship, and alleviating the isolation and pain of poverty and hunger, to dedicating their lives to working with underserved populations and people of all backgrounds in need of support, the awardees humbly devote themselves to making our communities a better place. Archbishop Listecki’s Treasures of the Church Award was established to recognize individuals, organizations and religious orders who exemplify the true treasures of the church in their steadfast commitment and response to the poor in our midst. Fashioned after an effort that began in 2006 in LaCrosse, “In My Name,” when then Bishop Listecki shepherded that diocese and its local Catholic Charities, Treasures of the Church is now an annual event that benefits the programs and services of Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. -

Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities

religions Article Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities Christopher Jain Miller 1 and Jonathan Dickstein 2,* 1 Department of Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA 90045, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Religious Studies, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93101, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article seeks to elevate contemporary Jain voices calling for the adoption of a vegan lifestyle as a sign of solidarity with the transnational vegan movement and its animal rights, envi- ronmental protection, and health aspirations. Just as important, however, this article also seeks to present some of the unique features of contemporary Jain veganism, including, most specifically, Jain veganism as an ascetic practice aimed at the embodiment of non-violence (ahim. sa¯), the eradication (nirjara¯) of karma, and the liberation (moks.a) of the Self (j¯ıva). These are distinctive features of Jain ve- ganism often overlooked and yet worthy of our attention. We begin the article with a brief discussion of transnational veganism and Jain veganism’s place within this global movement. This is followed by an overview of Jain karma theory as it appears in the Tattvartha¯ Sutra¯ , an authoritative diasporic Jain text. Next, we present two case studies of contemporary Jain expressions of veganism: (1) The UK-based organization known as “Jain Vegans” and (2) The US-based organization known as “Vegan Jains”. Both organizations have found new opportunities in transnational veganism to practice and embody the virtue of ahim. sa¯ as well as Jain karma theory. As we will show, though both organizations share the animal, human, and environmental protection aspirations found in transnational veganism, Jain Vegans and Vegan Jains simultaneously promote ahim. -

SADAQA and TZEDAKAH- Giving to Others PURPOSE the Goal of This

SADAQA AND TZEDAKAH- Giving to Others PURPOSE The goal of this session is for participants to develop a basic understanding of the role of sadaqa and tzedakah in our faith as well as in our personal lives PARTICIPANT OBJECTIVES To begin to learn and to ask questions. Both the Jewish and Muslim traditions place a strong emphasis on helping those less fortunate. This concept is based on the idea that our own good fortune is given to us from God and we, therefore, are obligated to share with those who do not have. This can take the form of either giving money or giving time. These two avenues of contributing to the community are shared by both religions, allowing Muslims and Jews to work together to create a more just society. PROCESS Since facilitating personal encounters is very difficult, this lesson includes more explicit instructions on how to run the session than subsequent lessons will have. Have copies available for all of the women to read during the meeting and to then engage in dialogue. FOR GROUP PARTICIPATION AND DISCUSSION Qur’anic and Biblical Texts on “Charity” Qur’an 2:177 It is not righteousness that you turn your faces toward East or West; but it is righteousness to believe in God, and the Last Day, and the angels, and revelation, and (God’s) messengers; to spend of your substance out of love for Him for your relatives, for orphans, for the needy, for the wayfarer, for those who seek assistance, and for the freeing of human beings from bondage; to be steadfast in prayer and practice regular charity; to fulfill the contracts that you have made; and to be firm and patient in distress, in adversity, and throughout all times of peril. -

Jane Addams and Charity Organization in Chicago

-DQH$GGDPVDQG&KDULW\2UJDQL]DWLRQLQ&KLFDJR $XWKRU V (ULN6FKQHLGHUKDQ 6RXUFH-RXUQDORIWKH,OOLQRLV6WDWH+LVWRULFDO6RFLHW\ 9RO1R :LQWHU SS 3XEOLVKHGE\Illinois State Historical Society 6WDEOH85/http://www.jstor.org/stable/40204699 . $FFHVVHG Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-). http://www.jstor.org Jane Addams and Charity Organization in Chicago Erik Schneiderhan1 Jane Addams has been studied almost to exhaustion. Scores of articlesand dissertationsattest to the importanceof her place in American history and society. Her papers, as well as any documents linked to her, however tenuously, were catalogued as part of the Jane Addams Papers Project and are on microfilmat universities across the world. In the past three years alone, two excellent and substantial biographies of Addams2 have been published. It seems reasonable to conclude that in the realm of Addams scholarship,the celebratedwords in Ecclesiastesring true: "Thereis nothing new under the sun." Or is there? This article presents some surprisingnew evidence of Addams's significant involvement in the early stages of charityorganization development in Chicago duringthe latterpart of the 19th century. -

In Islamic Economies Author: Adam Bukowski Source: ‘Annales

Social Role of Alms (zakat) in Islamic Economies Author: Adam Bukowski Source: ‘Annales. Ethics in Economic Life’ 2014, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 123-131 Published by Lodz University Press Stable URL: http://www.annalesonline.uni.lodz.pl/archiwum/2014/2014_4_bukowski_123_131.pdf Social Role of Alms (zakat) in Islamic Economies Autor: Adam Bukowski Artykuł opublikowany w „Annales. Etyka w życiu gospodarczym” 2014, vol. 17, nr 4, s. 123-131 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego Stable URL: http://www.annalesonline.uni.lodz.pl/archiwum/2014/2014_4_bukowski_123_131.pdf © Copyright by Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź 2014 Annales. Etyka w życiu gospodarczym / Annales. Ethics in Economic Life 2014 Vol. 17, No. 4, December 2014, 123-131 Adam Bukowski University of Lodz, Institute of Economics Department of the History of Economic Thought and Economic History email: [email protected] Social Role of Alms (zakāt) in Islamic Economies Abstract Islam as both religion and socioeconomic system is based on five main pillars, that is – five basic acts considered mandatory by Muslims, summarized in the hadith of Gabriel. One of them is zakāt (almsgiving), i.e. giving 2.5% of one’s wealth to the poor and needy. In contrary to Christian religion, where question of charity is rather of a vol- untary matter, the role of zakāt in Islam is much more rigidly described. Almsgiv- ing is considered as a duty of a pious Muslim towards the poor. Thus in Islamic economy, strongly based on Islam principles given by Allah to Muhammad, zakāt is imposed by law and is not considered a charity but duty rather. The notion of zakāt is mentioned in Qur-an over a 100 times, solely or in conjunction with other commandments.