Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

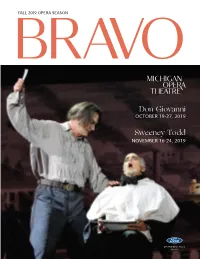

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Of Becoming and Remaining Vegetarian

Wang, Yahong (2020) Vegetarians in modern Beijing: food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/77857/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Vegetarians in modern Beijing: Food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience Yahong Wang B.A., M.A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow March 2019 1 Abstract This study investigates how self-defined vegetarians in modern Beijing construct their identity through everyday experience in the hope that it may contribute to a better understanding of the development of individuality and self-identity in Chinese society in a post-traditional order, and also contribute to understanding the development of the vegetarian movement in a non-‘Western’ context. It is perhaps the first scholarly attempt to study the vegetarian community in China that does not treat it as an Oriental phenomenon isolated from any outside influence. -

Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK 1 National Newspapers Bjos 1348 134..152

The British Journal of Sociology 2011 Volume 62 Issue 1 Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK 1 national newspapers bjos_1348 134..152 Matthew Cole and Karen Morgan Abstract This paper critically examines discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers in 2007. In setting parameters for what can and cannot easily be discussed, domi- nant discourses also help frame understanding. Discourses relating to veganism are therefore presented as contravening commonsense, because they fall outside readily understood meat-eating discourses. Newspapers tend to discredit veganism through ridicule, or as being difficult or impossible to maintain in practice. Vegans are variously stereotyped as ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists. The overall effect is of a derogatory portrayal of vegans and veganism that we interpret as ‘vegaphobia’. We interpret derogatory discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers as evidence of the cultural reproduction of speciesism, through which veganism is dissociated from its connection with debates concerning nonhuman animals’ rights or liberation. This is problematic in three, interrelated, respects. First, it empirically misrepresents the experience of veganism, and thereby marginalizes vegans. Second, it perpetuates a moral injury to omnivorous readers who are not presented with the opportunity to understand veganism and the challenge to speciesism that it contains. Third, and most seri- ously, it obscures and thereby reproduces -

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH

NUMBER 46 2017 GAJAHJournal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group Number 46 (2017) The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and conservation of Asian elephants both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by which everyone concerned with the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), whether members of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group or not, can communicate their research results, experiences, ideas and perceptions freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the Asian Elephant Specialist Group. Editor Dr. Jennifer Pastorini Centre for Conservation and Research 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Julpallama, Tissamaharama Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Dr. Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando School of Geography Centre for Conservation and Research University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Kajang, Selangor Julpallama, Tissamaharama Malaysia Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Varun R. Goswami Heidi Riddle Wildlife Conservation Society Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary 551, 7th Main Road P.O. Box 715 Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, 2nd Phase, Kodigehall Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058 Bengaluru - 560 097 USA India e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. T. N. C. Vidya -

April Breakfast Menu

Gustine ISD Pancakes Syrup Sausage Milk and Juice Variety Served Daily Pineapple HOLIDAY HS Fresh Fruit Served Daily Juice Menu Subject to Change Milk Biscuits Pancake Wrap Breakfast Pizza Cinnamon Roll Gravy Syrup HOLIDAY Pears Eggs Yogurt Sausage Juice Bacon Mandarin Oranges Peaches Mixed Fruit Milk Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Pancakes Cheesy Toast Chicken-n-Biscuit Breakfast Bread Breakfast Burritos Bacon Sausage Peaches Yogurt Hashbrowns Pineapple Pears Juice Mixed Fruit Mandarin Oranges Syrup Juice Milk Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Milk Sausage Kolache Cheese Omelet Waffles Breakfast Pizza Donuts Yogurt Toast Sausage Mandarin Oranges Sausage Peaches Pineapple Syrup Juice Mixed Fruit Juice Juice Pears Milk Juice Milk Milk Juice Milk Milk Biscuit Pancakes Breakfast Burritos Gravy Breakfast Bread Sausage Hashbrowns Eggs Yogurt Bacon Syrup Mixed Fruit Pineapple HOLIDAY Pears Peaches Juice Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Milk Art contest deadline April 2 “Moon milk” The moon is more than 200,000 miles away from the Earth. At this distance it takes about three full days for astronauts to travel from the Earth’s surface to land on the moon. Because it is Earth’s closest neighbor, we have been able to gain more knowledge about it than any other body in the Solar System besides the Earth. The moon is also the brightest object in the night sky. Today, astronomers know that the moon is slowly moving away from the Earth. But at the rate it is traveling, about 1.5 inches per year, it will be lighting up our night sky for a long time. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

A Non-Violent Politics? Vegetarianism, Religion, and the State in Eighteenth-Century Western India

Divya Cherian, Draft: Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission. A Non-Violent Politics? Vegetarianism, Religion, and the State in Eighteenth-Century Western India Divya Cherian Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis Scholarly discussions of the place of non-human animals in Hindu and Jain ethics, ritual, and everyday life generally place the principle of ahimsā or non-injury at the very center. An adherence to non-injury is an ethical injunction imposed by these two major South Asian religions (in addition to Buddhism) upon their practitioners. In principle, the Jain, Buddhist, and Vaishnav insistence upon non-injury is a universal one, that is, their ethical codes do not make a distinction between human and non-human animals as objects of compassion and non-injury. At the same time, Hindu and Jain attitudes towards animals are complex, even inconsistent. While in certain respects, neither Hindu nor Jain thought draws a distinction between the jiv (soul) of a human and a non-human, both religions do in other contexts differentiate among and hierarchize different types of beings. Taking differences in the potential to attain liberation from the cycle of birth-death-rebirth as the metric, both Jainism and Hinduism place humans at the pinnacle of a hierarchical conception of life forms. Despite this complexity in their approach to the distinction between humans and animals, the law codes of Jainism and several strands of Hinduism nonetheless enjoin upon their followers an adherence to non-injury towards all life forms. This however was not always the case. -

219 No Animal Food

219 No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944 Leah Leneman1 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH There were individuals in the vegetarian movement in Britain who believed that to refrain from eating flesh, fowl, and fish while continuing to partake of dairy products and eggs was not going far enough. Between 1909 and 1912, The Vegetarian Society's journal published a vigorous correspond- ence on this subject. In 1910, a publisher brought out a cookery book entitled, No Animal Food. After World War I, the debate continued within the Vegetarian Society about the acceptability of animal by-products. It centered on issues of cruelty and health as well as on consistency versus expediency. The Society saw its function as one of persuading as many people as possible to give up slaughterhouse products and also refused journal space to those who abjured dairy products. The year 1944 saw the word "vergan" coined and the breakaway Vegan Society formed. The idea that eating animal flesh is unhealthy and morally wrong has been around for millennia, in many different parts of the world and in many cultures (Williams, 1896). In Britain, a national Vegetarian Society was formed in 1847 to promulgate the ideology of non-meat eating (Twigg, 1982). Vegetarianism, as defined by the Society-then and now-and by British vegetarians in general, permitted the consumption of dairy products and eggs on the grounds that it was not necessary to kill the animal to obtain them. In 1944, a group of Vegetarian Society members coined a new word-vegan-for those who refused to partake of any animal product and broke away to form a separate organization, The Vegan Society. -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

Buddhist, Jaina, Gandhian & Peace Studies

JK SET Exam P r e v i o u s P a p e r SET 2013 PAPER – III BUDDHIST, JAINA, GANDHIAN AND PEACE STUDIES Signature of the Invigilator Question Booklet No. .................................... 1. OMR Sheet No.. .................................... Subject Code 08 ROLL No. Time Allowed : 150 Minutes Max. Marks : 150 No. of pages in this Booklet : 12 No. of Questions : 75 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CANDIDATES 1. Write your Roll No. and the OMR Sheet No. in the spaces provided on top of this page. 2. Fill in the necessary information in the spaces provided on the OMR response sheet. 3. This booklet consists of seventy five (75) compulsory questions each carrying 2 marks. 4. Examine the question booklet carefully and tally the number of pages/questions in the booklet with the information printed above. Do not accept a damaged or open booklet. Damaged or faulty booklet may be got replaced within the first 5 minutes. Afterwards, neither the Question Booklet will be replaced nor any extra time given. 5. Each Question has four alternative responses marked (A), (B), (C) and (D) in the OMR sheet. You have to completely darken the circle indicating the most appropriate response against each item as in the illustration. AB D 6. All entries in the OMR response sheet are to be recorded in the original copy only. 7. Use only Blue/Black Ball point pen. 8. Rough Work is to be done on the blank pages provided at the end of this booklet. 9. If you write your Name, Roll Number, Phone Number or put any mark on any part of the OMR Sheet, except in the spaces allotted for the relevant entries, which may disclose your identity, or use abusive language or employ any other unfair means, you will render yourself liable to disqualification. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ...........................................