The First Romanovs. (1613-1725)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

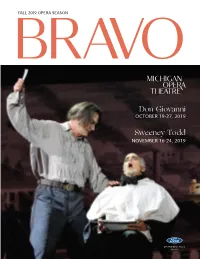

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

IN FO R M a TIO N to U SERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced from the Microfilm Master. UMI Films the Text Directly From

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed through, substandard margin*, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Ben A Howeii Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.761-4700 800.521-0600 RENDERING TO CAESAR: SECULAR OBEDIENCE AND CONFESSIONAL LOYALTY IN MORITZ OF SAXONY'S DIPLOMACY ON THE EVE OF THE SCMALKALDIC WAR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James E. -

![Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8843/asadisa-d%C4%81na-vatthu-the-incomparable-giving-the-joy-of-giving-dha-13-10-3-182-192-translated-annotated-by-piya-tan-%C2%A92008-518843.webp)

Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008

Dhammapad’aṭṭha,kathā vol 3 DhA 13.10 Asadisa,dāna Vatthu Asadisa,dāna Vatthu The Incomparable Giving [The joy of giving] (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2008 1 Dhammapada Story: The incomparable gift While the Āditta Jātaka (J 424) tells the story of the past regarding the incomparable giving (asadi- sa,dāna),1 the Dhammapada Commentary on Dh 177 (DhA 13.10) has the story of the present—the Asadisa,dāna Vatthu—regarding the same incomparable giving made by the rajah Pasenadi to the Buddha himself. The Āditta Jātaka commentary refers to the Mahā Govinda Sutta (D 19) commentary for the full story (DA 2:652-655). ——— 2 The Incomparable Giving (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) “The miserly certainly do not…” (na ve kadariyā). This Dharma teaching was given by the Teacher while he was staying in the Jeta,vana, with reference to the incomparable giving (asadisa,dāna). [183] 2.1 PASENADI AND CITIZENS OFFER ALMS. At one time, the Teacher, with a retinue of 500 monks, having wandered about, entered Jeta,vana. The king went to the monastery, invited the Teacher, and on the following day, had an incidental alms-giving [alms-giving for guests] (āgantuka,dāna) prepared, and announced to the city, “Come and see my giving!” On the next day, the citizens came, saw the king’s alms-giving, and then invited the Buddha for an alms-giving on the following day, and sent word to the king, “Your majesty, please come and see our giving.” The king saw their alms-giving and thought, “They have made a greater giving than mine. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Governance on Russia's Early-Modern Frontier

ABSOLUTISM AND EMPIRE: GOVERNANCE ON RUSSIA’S EARLY-MODERN FRONTIER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Paul Romaniello, B. A., M. A. The Ohio State University 2003 Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Eve Levin, Advisor Dr. Geoffrey Parker Advisor Dr. David Hoffmann Department of History Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle ABSTRACT The conquest of the Khanate of Kazan’ was a pivotal event in the development of Muscovy. Moscow gained possession over a previously independent political entity with a multiethnic and multiconfessional populace. The Muscovite political system adapted to the unique circumstances of its expanding frontier and prepared for the continuing expansion to its east through Siberia and to the south down to the Caspian port city of Astrakhan. Muscovy’s government attempted to incorporate quickly its new land and peoples within the preexisting structures of the state. Though Muscovy had been multiethnic from its origins, the Middle Volga Region introduced a sizeable Muslim population for the first time, an event of great import following the Muslim conquest of Constantinople in the previous century. Kazan’s social composition paralleled Moscow’s; the city and its environs contained elites, peasants, and slaves. While the Muslim elite quickly converted to Russian Orthodoxy to preserve their social status, much of the local population did not, leaving Moscow’s frontier populated with animists and Muslims, who had stronger cultural connections to their nomadic neighbors than their Orthodox rulers. The state had two major goals for the Middle Volga Region. -

The Swiss and the Romanovs

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 57 Number 2 Article 3 6-2021 The Swiss and the Romanovs Dwight Page Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Page, Dwight (2021) "The Swiss and the Romanovs," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 57 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol57/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Page: The Swiss and the Romanovs The Swiss and the Romanovs by Dwight Page For centuries, the Swiss people and government have sup- ported the cultural, intellectual, and economic objectives of the Rus- sian people and the Russian government. Especially during the Impe- rial Era of Russian history (1682-1917), the assistance provided to the ruling house of Russia by Swiss nationals was indispensable and of vital importance in helping the Russian royal house to achieve its cultural, political, pedagogical, and ecclesiastical goals.1 The Petrine Period (1682-1725) Contacts of some con- sequence between the Swiss and the House of Romanov started as early as the seven- teenth century, when a twenty- year-old Swiss soldier François Lefort came to Moscow in 1675 to serve the Romanov Dynasty, and soon reached a position of prominence. Although Czar 1 The Romanov Dynasty began to rule Russia in 1613 when, shortly after the Time of Troubles, Michael Romanov was accepted as the new Tsar by the boyars in Kostroma, at the Ipatieff Monastery. -

The Post Workshop Tour Round the Golden Ring of Russia

The Post Workshop Tour round the Golden Ring of Russia The Golden Ring is a symbolic ring of ancient Russian towns situated to the North- West from Moscow and is keeping unique monuments of the Ancient Russian architecture of the 12-17th centuries: Sergiev Posad and Alexandrov, Kostroma and Pereaslavl-Zalessky, Uglich and Ivanovo, Yaroslavl and Rostov the Great, Suzdal and Vladimir, each of these towns is a real pearl of Russia. Nowadays they are often called "museums in the open air". Cathedral and churches, convents and fine art museums strike by their beauty. A tour of the Golden Ring will give you a wonderful possibility to make the acquaintance of the history of ancient Russians towns, their culture and their traditions. The duration of the Tour: 5 days/ 4 nights Golden Ring Towns, which played the great role in the Russian ancient history: Vladimir – Suzdal – Kostroma – Yaroslavl - Rostov Veliky (Rostov the Great) - Pereslavl Zalessky - Sergiev Posad I Vladimir Vladimir is referred to as the gates to "Russian Golden Ring". The city came about at the end of the X century and is named after the Kiev-born prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich, the baptizer of Russia. The city was in its prime and achieved historical significance in the middle of the XII and beginning of the XIII centuries when the fundaments of a new government was forming. International trade and cultural relations were actively developing and the city opened its own architectural school. The defensive walls, the main city gates, the Golden gates, the gold-topped Uspensky Cathedral with frescoes by Andrei Rublev, and the Dmitrievsky cathedral are still preserved in Vladimir as proof of the past beauty and power of the former capital of Ancient Russia. -

Gustav V, King of Sweden (1858-1950) by Tina Gianoulis

Gustav V, King of Sweden (1858-1950) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A photograph of Crown Prince Gustav V of Sweden created in 1874. The last Swedish king to exert direct power over his nation's government, King Gustav Gustav ascended to the V was a memorable personality and a bisexual. Though his reign ended under a cloud throne in 1907. of scandal, he was instrumental in keeping his country neutral through two devastating world wars, passing progressive social legislation, and maintaining economic prosperity. Oscar Gustaf Adolf, who would later become Gustav, or Gustavus V, was born on June 16, 1858, in Stockholm's magnificent Drottningholm Palace. He was the eldest son of Oscar II, King of Sweden and Norway, which were united under one monarch until 1905, when Norway asserted its independence. Though a member of the royal house of Bernadotte, Crown Prince Gustaf was an unassuming young man who did not value regal pretensions. He was educated at the University of Uppsala. On a trip to Britain in 1878, he learned the game of tennis, which became a life-long passion. He often played incognito, under the pseudonym "Mr. G." In 1881, Crown Prince Gustaf married Victoria of Baden, a political union that united the Bernadottes with the former Swedish royal house of Vasa. Though they had three sons, the couple did not have a close relationship. Victoria's health was not good and she spent many months each year at the Swedish resort island of Solliden, Öland or on Capri in Italy. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p.