SADAQA and TZEDAKAH- Giving to Others PURPOSE the Goal of This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

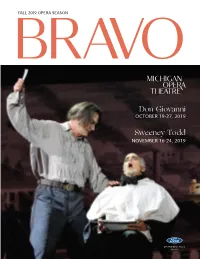

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

![Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8843/asadisa-d%C4%81na-vatthu-the-incomparable-giving-the-joy-of-giving-dha-13-10-3-182-192-translated-annotated-by-piya-tan-%C2%A92008-518843.webp)

Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008

Dhammapad’aṭṭha,kathā vol 3 DhA 13.10 Asadisa,dāna Vatthu Asadisa,dāna Vatthu The Incomparable Giving [The joy of giving] (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2008 1 Dhammapada Story: The incomparable gift While the Āditta Jātaka (J 424) tells the story of the past regarding the incomparable giving (asadi- sa,dāna),1 the Dhammapada Commentary on Dh 177 (DhA 13.10) has the story of the present—the Asadisa,dāna Vatthu—regarding the same incomparable giving made by the rajah Pasenadi to the Buddha himself. The Āditta Jātaka commentary refers to the Mahā Govinda Sutta (D 19) commentary for the full story (DA 2:652-655). ——— 2 The Incomparable Giving (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) “The miserly certainly do not…” (na ve kadariyā). This Dharma teaching was given by the Teacher while he was staying in the Jeta,vana, with reference to the incomparable giving (asadisa,dāna). [183] 2.1 PASENADI AND CITIZENS OFFER ALMS. At one time, the Teacher, with a retinue of 500 monks, having wandered about, entered Jeta,vana. The king went to the monastery, invited the Teacher, and on the following day, had an incidental alms-giving [alms-giving for guests] (āgantuka,dāna) prepared, and announced to the city, “Come and see my giving!” On the next day, the citizens came, saw the king’s alms-giving, and then invited the Buddha for an alms-giving on the following day, and sent word to the king, “Your majesty, please come and see our giving.” The king saw their alms-giving and thought, “They have made a greater giving than mine. -

Shabbat Bulletin

SHABBAT BULLETIN Rabbi Barry Gelman The Eruv is up. Rabbi Emeritus Joseph Radinsky z’l Cantor Emeritus Irving Dean President Mr. Rick Guttman LOUIS AND LEAH YAFFEE BNEI AKIVA PROGRAM: Shabbat No Teen Minyan 10:30 am: Tot Shabbat 4:10 pm Snif Groups: 1st—3rd in the tot trailer, 4th—5th in the Sukkah, 6th in the teen minyan trailer Serving the Orthodox Community of Parents are asked to tell their kids that card playing is not permitted in Houston for over 100 years the Synagogue. The presence of card playing does not promote the type of atmosphere we are trying to create in the shul. Additionally, all November 4, 2017 youth should either be in groups or sitting with their parents. 22 Cheshvan 5778 In recognition of our appreciation for all the help we received Torah Sefer: Bereishit during Hurricane Harvey, UOS is sponsoring a Kiddush this Shabbat Parasha: Chayei Sarah at both Beth Rambam and Young Israel. Haftarah: I Kings 1:1-31 ————————————— Shabbat Kiddush with chicken The annual UOS Congregation Annual Meeting salad in Freedman Hall. will take place on Sponsored by April and Kobi Sunday, December 10, 2017 Amsalem in gratitude to the com- at 9:00 am In Freedman Hall. munity and in honor of a positive reconstruction spirit. Seudah Shlishit 3 Part Mini Series Shabbat Kiddush next week: Join us on Shabbat afternoon as members of our community share their Sponsorship is greatly appreciated. expertise with us on issues related to Torah, Israel, Community and more. Seudah Shlishit in Freedman Hall. First Series: Dates: Nov. -

Dana Pāramī (The Perfection of Giving)

Dana Pāramī (The Perfection of Giving) Miss Notnargorn Thongputtamon Research Scholar, Department of Philosophy and Religion, Faculty of Arts, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India [email protected] Received Dec 14,2018; Revised Mar 4, 2019; Accepted May 29, 2019 ABSTRACT Every religion in the world likes to teach that charity is important. This is the case with Buddhism also. The Buddha describes the three central practices as Dana (generosity), Sila (morality) and Bhavana (meditation). Bhikkhu Bodhi writes, “the practice of giving is universally recognized as one of the most basic human virtues”, and Susan Elbaum Jootle confirms that it is a basis of merit or wholesome kamma and when practiced in itself, it leads ultimately to liberation from the cycle of repeated existence”. Buddhists do not seek publicity for charity. But it is the practice of the vehicle of great enlightenment (mahābodhiyāna) to improve their skillfulness in accumulating the requisites for enlightenment. We now undertake a detailed explanation of the Dana Pāramī. Keywords: Dana (generosity), Bhavana (meditation), Sila (morality) 48 The Journal of The International Buddhist Studies College What are the Pāramis? For the meaning of the Pāramīs, the Brahmajāla Sutta explains that they are the noble qualities such as giving and etc., accompanied by compassion and skillful means, untainted by craving and conceit views (Bhikkhu Bodhi, 2007). Traleg Kyabgon Rinpoche renders “pāramīs” into English as “transcendent action”. He understands “transcendent action” in the sense of non-egocentric action. He says: “Transcendental” does not refer to some external reality, but rather to the way in which we conduct our lives and perceive the world – either in an egocentric way or non-egocentric way. -

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~ Rosh HaShanah ~ S’lichot Service jointly w/ Ohavi Saturday September 12 8:00pm Zedek ~ Erev Rosh HaShanah Service Friday September 18 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Saturday September 19 9:00am ~ Morning Rosh HaShanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00am ~ Tashlich (location TBA) Saturday September 19 4:00pm ~ Insomniac Lounge: alternative Rosh Hashanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00pm Between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur ~ Shofar Drive-thru Sunday September 20 11:00am ~ JCVT Vermont Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 TBD Service ~ Insomniac Lounge: Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 10:00pm meditation service ~ Shabbat Shuva Morning Service Saturday September 26 9:30am ~ Shabbat Shuva Torah Study Saturday September 26 10:30am Yom Kippur ~ Kol Nidre/Erev Yom Kippur Sunday September 27 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Monday September 28 9:00am ~ Morning Yom Kippur Service Monday September 28 10:00am ~ Yizkor Service Monday September 28 2:00pm ~ Making Prayer Real: Engaging Yom Kippur Monday September 28 3:00 pm ~ Minchah Service Monday September 28 4:30pm ~ Neilah Monday September 28 6:00pm ~ Break Fast Monday September 28 7:00pm Join us on ZOOM This year's High Holy Day services will be a different experience to what we are used to. Our services will be led by our rabbi, David Edleson, and our cantor Mark Leopold. Due to the pandemic and the significantly heightened risks of singing in closed spaces, we will not be celebrating in the Sanctuary but will continue our worship on ZOOM as we have been every Shabbat. -

QUESTION 32 the Works of Mercy (Almsgiving)

QUESTION 32 The Works of Mercy (Almsgiving) We next have to consider almsgiving or the works of mercy. And on this topic there are ten questions: (1) Is almsgiving or doing a work of mercy (eleemosynae largitio) an act of charity? (2) How are the works of mercy divided? (3) Which are the most important works of mercy, the spiritual or corporal? (4) Do the corporal works of mercy have a spiritual effect? (5) Does doing the works of mercy fall under a precept? (6) Should a corporal work of mercy be done from resources that are necessary for one to live on? (7) Should a corporal work of mercy be done from resources that have been unjustly acquired? (8) Whose role is it to do the works of mercy? (9) To whom should the works of mercy be done? (10) How should the works of mercy be done? Article 1 Is almsgiving or doing a work of mercy an act of charity? It seems that almsgiving or doing a work of mercy (dare eleemosynam), is not an act of charity: Objection 1: An act of charity cannot exist in the absence of charity. But almsgiving can exist in the absence of charity—this according to 1 Corinthians 13:3 (“If I should distribute all my goods to feed the poor ... but do not have charity ...”). Therefore, almsgiving or doing a work of mercy is not an act of charity. Objection 2: The works of mercy (eleemosyna) are numbered among the acts of satisfaction—this according to Daniel 4:24 (“Redeem your sins with alms, and your iniquities with works of mercy for the poor”). -

The Treasure of Generosity South Bay to Educate the Community and Foster the Spirit of Dana—A Spirit That Recognizes and Manifests the Interdependent Nature of Being

The Treasure of Generosity This booklet has been published by Insight Meditation The Treasure of Generosity South Bay to educate the community and foster the spirit of dana—a spirit that recognizes and manifests the interdependent nature of being. The primary “If people knew, as I know, the results of giving and intent of this booklet is to encourage the cultivation sharing, they would not eat a meal without sharing it, and practice of dana. IMSB, like most religious and nor would they allow the taint of stinginess or meanness charitable organizations, depends upon donations to to overtake their minds.” sustain its operations. We encourage you to experience —The Buddha, Ittivutakkha 26 the treasures of generosity by giving in ways that retain Generosity is commonly defined as the act of freely the spirit of dana. giving or sharing what we have. The giving of money and material objects, the sharing of time, effort, and presence, and the sharing of teachings all are expressions of generosity. Generosity is at the heart of the Buddha’s teachings. In Buddhist traditions, the act of generosity is called dana, in the ancient Pali language. The inner disposition toward being generous is the less well-known Pali term, caga. The underlying spirit of dana, which began as townspeople offered support to monks and nuns on alms rounds, carries on to this day. Today, our own spiritual practices provide us with the opportunity to explore the rich relationship between dana and caga while pointing us toward a healthy manifestation of non-attachment, non-aversion, and interdependence. -

Donors Vastly Underestimate Differences in Charities' Effectiveness

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 15, No. 4, July 2020, pp. 509–516 Donors vastly underestimate differences in charities’ effectiveness Lucius Caviola∗† Stefan Schubert‡† Elliot Teperman David Moss§ Spencer Greenberg Nadira S. Faber¶ ‡ Abstract Some charities are much more cost-effective than other charities, which means that they can save many more lives with the same amount of money. Yet most donations do not go to the most effective charities. Why is that? We hypothesized that part of the reason is that people underestimate how much more effective the most effective charities are compared with the average charity. Thus, they do not know how much more good they could do if they donated to the most effective charities. We studied this hypothesis using samples of the general population, students, experts, and effective altruists in five studies. We found that lay people estimated that among charities helping the global poor, the most effective charities are 1.5 times more effective than the average charity (Studies 1 and 2). Effective altruists, in contrast, estimated the difference to be factor 50 (Study 3) and experts estimated the factor to be 100 (Study 4). We found that participants donated more to the most effective charity, and less to an average charity, when informed about the large difference in cost-effectiveness (Study 5). In conclusion, misconceptions about the difference in effectiveness between charities is thus likely one reason, among many, why people donate ineffectively. Keywords: cost-effectiveness, charitable giving, effective altruism, prosocial behavior, helping 1 Introduction interested behavior: e.g., people more frequently choose the most effective option when investing (for their own benefit) People donate large sums to charity every year. -

The Definition of Effective Altruism

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/08/19, SPi 1 The Definition of Effective Altruism William MacAskill There are many problems in the world today. Over 750 million people live on less than $1.90 per day (at purchasing power parity).1 Around 6 million children die each year of easily preventable causes such as malaria, diarrhea, or pneumonia.2 Climate change is set to wreak environmental havoc and cost the economy tril- lions of dollars.3 A third of women worldwide have suffered from sexual or other physical violence in their lives.4 More than 3,000 nuclear warheads are in high-alert ready-to-launch status around the globe.5 Bacteria are becoming antibiotic- resistant.6 Partisanship is increasing, and democracy may be in decline.7 Given that the world has so many problems, and that these problems are so severe, surely we have a responsibility to do something about them. But what? There are countless problems that we could be addressing, and many different ways of addressing each of those problems. Moreover, our resources are scarce, so as individuals and even as a globe we can’t solve all these problems at once. So we must make decisions about how to allocate the resources we have. But on what basis should we make such decisions? The effective altruism movement has pioneered one approach. Those in this movement try to figure out, of all the different uses of our resources, which uses will do the most good, impartially considered. This movement is gathering con- siderable steam. There are now thousands of people around the world who have chosen -

Testing for Altruism and Social Pressure in Charitable Giving∗

Testing for Altruism and Social Pressure in Charitable Giving∗ Stefano DellaVigna John A. List Ulrike Malmendier UC Berkeley and NBER UChicagoandNBER UC Berkeley and NBER This version: May 25, 2011 Abstract Every year, 90 percent of Americans give money to charities. Is such generosity necessar- ily welfare enhancing for the giver? We present a theoretical framework that distinguishes two types of motivation: individuals like to give, e.g., due to altruism or warm glow, and individuals would rather not give but dislike saying no, e.g., due to social pressure. We design a door-to-door fund-raiser in which some households are informed about the exact time of solicitation with a flyer on their door-knobs. Thus, they can seek or avoid the fund- raiser. We find that the flyer reduces the share of households opening the door by 9 to 25 percent and, if the flyer allows checking a ‘Do Not Disturb’ box, reduces giving by 28 to 42 percent. The latter decrease is concentrated among donations smaller than $10. These findings suggest that social pressure is an important determinant of door-to-door giving. Combiningdatafromthisandacomplementaryfield experiment, we structurally estimate the model. The estimated social pressure cost of saying no to a solicitor is $356 for an in-state charity and $137 for an out-of-state charity. Our welfare calculations suggest that our door-to-door fund-raising campaigns on average lower utility of the potential donors. ∗We thank the editor, four referees, Saurabh Bhargava, David Card, Gary Charness, Constanca Esteves- Sorenson, Bryan Graham, Zachary Grossman, Lawrence Katz, Patrick Kline, Stephan Meier, Klaus Schmidt, Bruce Shearer, Joel Sobel, Daniel Sturm and the audiences at the Chicago Booth School of Business, Columbia University, Harvard University, HBS, University of Amsterdam, University of Arizona, Tucson, UC Berkeley, USC (Marshall School), UT Dallas, University of Rotterdam, University of Zurich, Washington University (St.