Tzedakah As the Defining Social Marker of Jewish Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

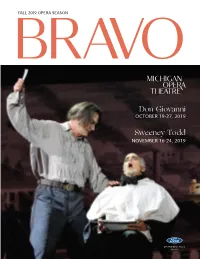

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

Understanding Mikvah

Understanding Mikvah An overview of Mikvah construction Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi S. Z. Lesches permission & comments: (514) 737-6076 4661 Van Horne, Suite 12 Montreal P.Q. H3W 1H8 Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Lesches, Schneur Zalman Understanding mikvah : an overview of mikvah construction ISBN 0-9689146-0-8 1. Mikveh--Design and construction. 2. Mikveh--History. 3. Purity, Ritual--Judaism. 4. Jewish law. I. Title. BM703.L37 2001 296.7'5 C2001-901500-3 v"c CONTENTS∗ FOREWORD .................................................................... xi Excerpts from the Rebbe’s Letters Regarding Mikvah....13 Preface...............................................................................20 The History of Mikvaos ....................................................25 A New Design.............................................................27 Importance of a Mikvah....................................................30 Building and Planning ......................................................33 Maximizing Comfort..................................................34 Eliminating Worry ......................................................35 Kosher Waters ...................................................................37 Immersing in a Spring................................................37 Oceans..........................................................................38 Rivers and Lakes .........................................................38 Swimming Pools .........................................................39 -

The Crucifiable Jesus

The Crucifiable Jesus Steven Brian Pounds Peterhouse Faculty of Divinity University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2019 This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my thesis has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee Steven Brian Pounds “The Crucifiable Jesus” Abstract: In recent decades, scholars have both used Jesus’ crucifixion as a criterion of historicity and employed the rhetoric of a “crucifiable Jesus”– suggesting that some historical reconstructions of Jesus more plausibly explain his crucifixion than others. This dissertation tests the grounds of these proposals, whilst offering its own reconstruction of a crucifiable Jesus. It first investigates primary source depictions of Roman crucifixion and focuses upon the offences for which crucifixions were carried out. As a first level conclusion, it determines that, in a formal sense, a bare appeal to crucifiability or to a criterion of crucifixion does not yield what it purports to deliver because a wide range of offences were punishable by crucifixion. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

![Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8843/asadisa-d%C4%81na-vatthu-the-incomparable-giving-the-joy-of-giving-dha-13-10-3-182-192-translated-annotated-by-piya-tan-%C2%A92008-518843.webp)

Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008

Dhammapad’aṭṭha,kathā vol 3 DhA 13.10 Asadisa,dāna Vatthu Asadisa,dāna Vatthu The Incomparable Giving [The joy of giving] (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2008 1 Dhammapada Story: The incomparable gift While the Āditta Jātaka (J 424) tells the story of the past regarding the incomparable giving (asadi- sa,dāna),1 the Dhammapada Commentary on Dh 177 (DhA 13.10) has the story of the present—the Asadisa,dāna Vatthu—regarding the same incomparable giving made by the rajah Pasenadi to the Buddha himself. The Āditta Jātaka commentary refers to the Mahā Govinda Sutta (D 19) commentary for the full story (DA 2:652-655). ——— 2 The Incomparable Giving (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) “The miserly certainly do not…” (na ve kadariyā). This Dharma teaching was given by the Teacher while he was staying in the Jeta,vana, with reference to the incomparable giving (asadisa,dāna). [183] 2.1 PASENADI AND CITIZENS OFFER ALMS. At one time, the Teacher, with a retinue of 500 monks, having wandered about, entered Jeta,vana. The king went to the monastery, invited the Teacher, and on the following day, had an incidental alms-giving [alms-giving for guests] (āgantuka,dāna) prepared, and announced to the city, “Come and see my giving!” On the next day, the citizens came, saw the king’s alms-giving, and then invited the Buddha for an alms-giving on the following day, and sent word to the king, “Your majesty, please come and see our giving.” The king saw their alms-giving and thought, “They have made a greater giving than mine. -

Shabbat Bulletin

SHABBAT BULLETIN Rabbi Barry Gelman The Eruv is up. Rabbi Emeritus Joseph Radinsky z’l Cantor Emeritus Irving Dean President Mr. Rick Guttman LOUIS AND LEAH YAFFEE BNEI AKIVA PROGRAM: Shabbat No Teen Minyan 10:30 am: Tot Shabbat 4:10 pm Snif Groups: 1st—3rd in the tot trailer, 4th—5th in the Sukkah, 6th in the teen minyan trailer Serving the Orthodox Community of Parents are asked to tell their kids that card playing is not permitted in Houston for over 100 years the Synagogue. The presence of card playing does not promote the type of atmosphere we are trying to create in the shul. Additionally, all November 4, 2017 youth should either be in groups or sitting with their parents. 22 Cheshvan 5778 In recognition of our appreciation for all the help we received Torah Sefer: Bereishit during Hurricane Harvey, UOS is sponsoring a Kiddush this Shabbat Parasha: Chayei Sarah at both Beth Rambam and Young Israel. Haftarah: I Kings 1:1-31 ————————————— Shabbat Kiddush with chicken The annual UOS Congregation Annual Meeting salad in Freedman Hall. will take place on Sponsored by April and Kobi Sunday, December 10, 2017 Amsalem in gratitude to the com- at 9:00 am In Freedman Hall. munity and in honor of a positive reconstruction spirit. Seudah Shlishit 3 Part Mini Series Shabbat Kiddush next week: Join us on Shabbat afternoon as members of our community share their Sponsorship is greatly appreciated. expertise with us on issues related to Torah, Israel, Community and more. Seudah Shlishit in Freedman Hall. First Series: Dates: Nov. -

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~ Rosh HaShanah ~ S’lichot Service jointly w/ Ohavi Saturday September 12 8:00pm Zedek ~ Erev Rosh HaShanah Service Friday September 18 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Saturday September 19 9:00am ~ Morning Rosh HaShanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00am ~ Tashlich (location TBA) Saturday September 19 4:00pm ~ Insomniac Lounge: alternative Rosh Hashanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00pm Between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur ~ Shofar Drive-thru Sunday September 20 11:00am ~ JCVT Vermont Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 TBD Service ~ Insomniac Lounge: Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 10:00pm meditation service ~ Shabbat Shuva Morning Service Saturday September 26 9:30am ~ Shabbat Shuva Torah Study Saturday September 26 10:30am Yom Kippur ~ Kol Nidre/Erev Yom Kippur Sunday September 27 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Monday September 28 9:00am ~ Morning Yom Kippur Service Monday September 28 10:00am ~ Yizkor Service Monday September 28 2:00pm ~ Making Prayer Real: Engaging Yom Kippur Monday September 28 3:00 pm ~ Minchah Service Monday September 28 4:30pm ~ Neilah Monday September 28 6:00pm ~ Break Fast Monday September 28 7:00pm Join us on ZOOM This year's High Holy Day services will be a different experience to what we are used to. Our services will be led by our rabbi, David Edleson, and our cantor Mark Leopold. Due to the pandemic and the significantly heightened risks of singing in closed spaces, we will not be celebrating in the Sanctuary but will continue our worship on ZOOM as we have been every Shabbat. -

Kabbalah As a Shield Against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: a Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer

Kabbalah as a Shield against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: A Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer Adiel Cohen The belief that the Torah was given by divine revelation, as defined by Maimonides in his eighth principle of faith and accepted collectively by the Jewish people,1 conflicts with the opinions of modern biblical scholarship.2 As a result, biblical commentators adhering to both the peshat (literal or contex- tual) method and the belief in the divine revelation of the Torah, are unable to utilize the exegetical insights associated with the documentary hypothesis developed by Wellhausen and his school, a respected and accepted academic discipline.3 As Moshe Greenberg has written, “orthodoxy saw biblical criticism in general as irreconcilable with the principles of Jewish faith.”4 Therefore, in the words of D. S. Sperling, “in general, Orthodox Jews in America, Israel, and elsewhere have remained on the periphery of biblical scholarship.”5 However, the documentary hypothesis is not the only obstacle to the religious peshat commentator. Theological complications also arise from the use of archeolog- ical discoveries from the ancient Near East, which are analogous to the Torah and can be a very rich source for its interpretation.6 The comparison of biblical 246 Adiel Cohen verses with ancient extra-biblical texts can raise doubts regarding the divine origin of the Torah and weaken faith in its unique sanctity. The Orthodox peshat commentator who aspires to explain the plain con- textual meaning of the Torah and produce a commentary open to the various branches of biblical scholarship must clarify and demonstrate how this use of modern scholarship is compatible with his or her belief in the divine origin of the Torah.