Increasing Investment in Germany in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geschäftsbericht 2019 Wege Sind Unser Ziel

Geschäftsbericht 2019 Wege sind unser Ziel Geschäftsbericht 2019 Wege sind unser Ziel Herausgeber: DEGES Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH Zimmerstraße 54 10117 Berlin Tel. 030 20243-0 Fax 030 20243-291 [email protected] Konzeption/Redaktion: DEGES, Abteilung Kommunikation Fotografien und Karten: DEGES; Illing & Vossbeck Fotografie; LAP/gmp; René Legrand; Nürnberg Luftbild, Hajo Dietz; Martin Pippert; Caroline Schlüter; Studio Mittelmühle Gesamtherstellung: Aktiva GmbH, Berlin Veröffentlichung: Oktober 2020 Änderungen und Irrtümer vorbehalten. Gedruckt auf 100 % Altpapier, FSC-zertifiziert und mit EU-Eco-Label ausgezeichnet DEGES Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH 5 Inhalt Organe Gesellschafter 6 Aufsichtsrat 7 Vorwort der Geschäftsführung 8 Bericht der Geschäftsführung Grundlagen der Gesellschaft 12 Unternehmensgegenstand und Geschäftsmodell 12 Projektportfolio 13 Geschäftsverlauf 2019 16 Stand der Projektrealisierung 16 Geschäftsvolumen 20 Organisatorische Änderungen 21 Vermögens-, Finanz- und Ertragslage 21 Leistungsbezogene Kennzahlen 23 Personalentwicklung 26 Chancen- und Risikobeurteilung 26 Prognosebericht 27 Höhepunkte des Jahres 2019 28 Bericht des Aufsichtsrates / Jahresabschluss Bericht des Aufsichtsrates für das Geschäftsjahr 2019 34 Bestätigungsvermerk des Abschlussprüfers 35 Bilanz zum 31. Dezember 2019 38 Gewinn- und Verlustrechnung 39 Betreute Bau-, Grunderwerbs- und weitere Projektleistungen sowie hierfür verwendete Mittel zum 31. Dezember 2019 40 Anhang für das Geschäftsjahr 2019 41 Titelbild: -

Jahresabschluss 2009. DEGES

Bundesanzeiger Name Bereich Information V.-Datum Deges Deutsche Einheit Rechnungslegung/ Jahresabschluss zum Geschäftsjahr vom 11.11.2010 Fernstraßenplanungs- und -Bau-GmbH Finanzberichte 01.01.2009 bis zum 31.12.2009 Berlin DEGES Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau-GmbH Berlin Jahresabschluss vom 01. Januar bis 31. Dezember 2009 Inhalt Lagebericht für das Geschäftsjahr 2009 Bilanz zum 31. Dezember 2009 Gewinn- und Verlustrechnung für die Zeit vom 01 . Januar bis 31. Dezember 2009 Anhang für das Geschäftsjahr 2009 Vorschlag für die Verwendung des Jahresüberschusses 2009 Lagebericht für das Geschäftsjahr 2009 1. Aufgaben der Gesellschaft Der Gegenstand des Unternehmens ist die Planung und Baudurchführung (Bauvorbereitung und Bauüberwachung) von und für Bundesfernstraßen oder wesentliche Teile davon im Rahmen der Auftragsverwaltung gemäß Artikel 90 Grundgesetz. Entsprechendes gilt für vergleichbare Verkehrsinfrastrukturprojekte in der Baulast der Gesellschafter einschließlich zugehöriger Aufgaben. Die Beauftragung erfolgt jeweils auf der Grundlage des Inhouse-Modells durch Dienstleistungsverträge mit dem beauftragenden Gesellschafter. Gesellschafter der DEGES sind: • Bundesrepublik Deutschland • Land Brandenburg • Freie Hansestadt Bremen (seit Dezember 2009) • Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg • Land Mecklenburg-Vorpommern • Freistaat Sachsen • Land Sachsen-Anhalt • Land Schleswig-Holstein • Freistaat Thüringen Die Gesellschafter haben die DEGES mit der Planung und/oder Baudurchführung • eines Großteils der Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche -

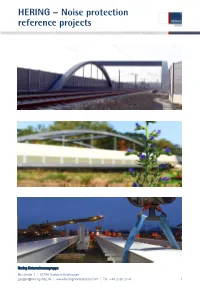

References Noise Protection

HERING – Noise protection HERINGreference - Reference projects projects Hering Unternehmensgruppe Neuländer 1 | 57299 Burbach-Holzhausen [email protected] | www.heringinternational.com | Tel.: +49 2736 27-0 1 Noise protection Building DB Netz AG ErfurtKnoten - HalleIlmenau VP41 (Halle junction) owner: Max Bögl Client: Project: VDE German Reunification Transportation Project 8, Erfurt- Ilmenau section, Train speed up to 300 km/h Services: Supply of eight bridge structures with 6,233 m² of noise and wind barriers Construction August 2013 to March 2014 period: Order volume: ca. 2,000,000.00 euros Building DB Netz AG ErlangenMerzig - Bruck owner: Max Bögl Client: Project: Line section on the ICE Nuremberg - Leipzig line Train speed up to 200 km/h Construction June to September 2013 period: Order volume: ca. 2,166,000.00 euros Hering Unternehmensgruppe Neuländer 1 | 57299 Burbach-Holzhausen [email protected] | www.heringinternational.com | Tel.: +49 2736 27-0 2 Noise protection Building DB Netz AG owner: Coburg Porr Bau GmbH Knoten Halle VP41 Client: Infrastructure Dept. - Railroad Construction Project: VDE German Reunification Transportation Project 8, Coburg section, Train speed up to 300 km/h Services: Construction of a 16-km stretch of noise barriers on bridges and 10 km of noise barriers along the line Construction October 2013 to ca. end of 2015 period: Order volume: ca. 9,500,000.00 euros Building DB Netz AG, Frankfurt am Main owner: Merzig Holzwickede - Schwerte Ed. Züblin AG Client: Bavaria/System construction department Noise protection sector Project: Holwickede-Schwerte line Services: Supply and assembly of 13 torsion beams with noise barriers, assembly by the Hering Bau railway crane fleet Construction July 2013 to February 2014 period: Order volume: ca. -

Building a Platform for Efficient Collaboration That Is Ready for the Future

Building a platform for efficient collaboration that is ready for the future Customer Success Story: Nextcloud at DEGES July 2019 2 CASE STUDY | DEGES CASE STUDY | DEGES 3 Key points Project overview • Employees demand easy to use, efficient collaboration technology Goal: Providing digital infrastructure for distributed collaboration Industry: Semi-public project management organization • Introduced Nextcloud Enterprise File Sync and Share solution for document exchange Employees: 350 to be provided with private EFSS • Integrated in existing infrastructure, processes and workflows Solution: Nextcloud Files Integration: NTFS , user directory, existing ECM Highlight: Project space for document exchange and collaboration with hundreds of external participants “The flood of documents was growing and the call for an online collaboration was getting louder.“ Jens Düssel, Department Head IT and Organisation 4 CASE STUDY | DEGES CASE STUDY | DEGES 5 About DEGES “Ease of use and ability to self-manage were key for users and acceptance of Nextcloud As a project management company for complex transport infrastructure projects, it is the task of DEGES to solution was immediate and enthusiastic.” economically plan transport routes, whether road, rail or waterway. In a complex and distributed project and quality management system, DEGES coordinates, optimises and manages the services of external planners Jens Düssel, Department Head IT and Organisation and architects, land purchasers, construction supervisors, construction companies and other service -

Gemeinsam Wachsen Finanzierungs- Und Realisierungsplan (FRP) 2021 Bis 2025 Für Die Bundesautobahnen Und Bundesstraßen in Bundesverwaltung Stand: 23

Gemeinsam wachsen Finanzierungs- und Realisierungsplan (FRP) 2021 bis 2025 für die Bundesautobahnen und Bundesstraßen in Bundesverwaltung Stand: 23. November 2020 Finanzierungs- und Realisierungsplan (FRP) 2021 bis 2025 für die Bundesautobahnen und Bundesstraßen in Bundesverwaltung 1. Hintergrund 3 2. Strategie der Autobahn GmbH zur Erreichung der Reformziele 5 3. Investitionsbedarf des FRP 2021–2025 6 4. Projektlisten des FRP 2021–2025 9 Tabellen Finanzplanung 2021–2025 für Bundesautobahnen und Bundesstraßen in Bundesverwaltung 6 Übersicht Bedarfsplan und ÖPP: Teil A — laufende Projekte 11 Übersicht Bedarfsplan und ÖPP: Teil B — bis 2025 neu zu beginnende Projekte 11 Übersicht Bedarfsplan und ÖPP: Teil C — weitere wichtige Projekte 11 Übersicht Um- und Ausbau (ohne Rastanlagen) 11 Übersicht Erhaltung 12 Abbildungen Investitionsbedarf 2021–2025 für Bundesautobahnen und Bundesstraßen in Bundesverwaltung 8 Anlage: Projektlisten Bedarfsplan: Teil A — laufende Projekte nach Bundesautobahnen 13 Bedarfsplan: Teil A — laufende Projekte nach Ländern 21 Bedarfsplan: Teil B — bis 2025 neu zu beginnende Projekte nach Bundesautobahnen 30 Bedarfsplan: Teil B — bis 2025 neu zu beginnende Projekte nach Ländern 39 Bedarfsplan: Teil C — weitere wichtige Projekte nach Bundesautobahnen 50 Bedarfsplan: Teil C — weitere wichtige Projekte nach Ländern 56 Um- und Ausbaumaßnahmen 62 Erhaltungsmaßnahmen 66 Sonstiges 70 2 1. Hintergrund Der Bund ist gemäß dem Grundgesetz verantwortlich für den Bau und die Erhaltung der Bundesverkehrswege (Bundesschienenwege: Art. 87e GG, Bundeswasserstraßen: Art. 89 Abs. 2 GG, Bundesfernstraßen: Art. 90 GG). Zentrales Planungsinstrument hierfür ist der Bundesverkehrswegeplan – kurz BVWP. Der aktuelle BVWP 2030 wurde 2016 vom Bundeskabinett verabschiedet und stellt das verkehrsträgerübergreifende Gesamtkonzept der Bundesregierung dar. Er besitzt keinen Gesetzescharakter, bildet aber die Basis für alle Ausbaugesetze für Straße und Schiene mit den entsprechenden Bedarfsplänen. -

In Everyday Project Life Foreword Contents

Special IN EVERYDAY PROJECT LIFE FOREWORD CONTENTS 7 19 23 2 FOREWORD 19 Construction of New Spree 26 A new life for a shipyard 32 Ship repair facility in India Dear readers, Secondary School harbour Planning and design work is pro- Technical implementation is 4 NEWS Two central models were develo- gressing well on the project near BIM off ers great potential for optimising planning, design and construction ped on the basis of multi-offi ce supported by a BIM-GIS integration the city of Cochin in southern India processes, but implementing it presents challenges for us as a company – for collaboration example, in developing the necessary IT skills and adapting personnel and 8 FOCUS 28 Port development projects in 35 IMPRINT responsibility structures. To ensure sustainable future-readiness, we have 21 Hadeln Canal Lock on the East Africa placed a strong focus in recent years on digitising our work processes. In 8 BIM in everyday project life Elbe-Weser-Waterway Inros Lackner is one of the region’s the past year, for instance, we successfully developed a program tool that Conversation with Gregor Gebert BIM also off ers interesting possi- most dependable suppliers of mariti- transforms CPIXML road design data into IFC-compatible data. But despite of the DEGES highway planning me engineering consultancy services all the euphoria about BIM, it is our technical experience and knowledge bilities and prospects in hydraulic that are most important in enabling us to achieve project goals – specialist and construction company construction engineeriing 30 Shipping routes in West Africa know-how, that thanks to BIM can be applied more effi ciently in the future. -

"Nature`S Jewels"

NATURA 2000 IN GERMANY Nature´s jewels IMPRESSUM Titelbild Verzeichnis der Autoren Wildkatze im Buchenwald (Fotos: A. Hoffmann, Th. Stephan) · Balzer, Sandra (Bundesamt für Naturschutz), Kap. 14 Collage: cognitio · Beinlich, Burkhard (Bioplan Höxter / Marburg), Kap. 6, 7, 13 · Bernotat, Dirk (Bundesamt für Naturschutz), Kap. 10 Redaktion · Dieterich, Martin (ILN Singen), Kap. 8, 12, 13 · Axel Ssymank, Sandra Balzer, Bundesamt für Naturschutz, · Engels, Barbara (Bundesamt für Naturschutz), Kap. 15 Fachgebiet I.2.2 „FFH-Richtlinie und Natura 2000“ · Hill, Benjamin (Bioplan Höxter / Marburg), Kap. 6, 7, 15 · Christa Ratte, BMU, Ref. NI2 „Gebietsschutz“ · Janke, Klaus (Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Behörde für Stadt- · Martin Dieterich, Christina Drebitz, ILN Singen entwicklung und Umwelt, Referatsleitung Europäischer Naturschutz · Burkhard Beinlich, Benjamin Hill, Bioplan Höxter / Marburg & Nationalpark Hamburgisches Wattenmeer), Kap. 5 · Köhler, Ralf (Landesumweltamt Brandenburg), Kap. 8 Bildredaktion · Krause, Jochen (Bundesamt für Naturschutz), Kap. 9 Frank Grawe, Landschaftsstation im Kreis Höxter · Ssymank, Axel (Bundesamt für Naturschutz), Kap. 1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12 Christina Drebitz, ILN Singen · Wollny-Goerke, Katrin, Kap. 9 Die Erstellung der Broschüre erfolgte im Rahmen eines F + E Vorhabens Glossar „Natura 2000 in Deutschland, Präsentation des Schutzgebietsnetzes · Beulhausen, Friederike; Balzer, Sandra; Ssymank, Axel (Bundesamt für die Öffentlichkeit“ (FKZ 806 82 280) mit Fördermitteln des Bundes für Naturschutz) und unter Beteiligung -

Liste Der Planungs- Und Bestandsauditoren Nach Postleitzahlen Stand: 23.09.2021

Liste der Planungs- und Bestandsauditoren nach Postleitzahlen Stand: 23.09.2021 zertifizierter Auditor für Haupt- Erschlie- Akad. Grad/ Auditor Auto- Land- Ortsdurch- PLZ / Land Name Vorname Dienststelle verkehrs- ßungs- Titel seit bahnen straßen fahrten straßen straßen Landeshauptstadt Dresden 1 01001 Friedemann Marina Dipl.-Ing. 2004 X X X Straßen- und Tiefbauamt Landeshauptstadt Dresden 2 01001 Jarosch Gerd Dipl.-Ing. 2006 X X X Straßen- und Tiefbauamt Landeshauptstadt Dresden 3 01001 Wilke Sabine Dipl.-Ing. 2006 X X X Straßen- und Tiefbauamt Landeshauptstadt Dresden 4 01067 Schade Jens-Uwe Stadtplanungsamt 2004 X X X Freiberger Straße 39 Landeshauptstadt Dresden 5 01067 Zschoge Andre Dipl.-Ing. Stadtplanungsamt 2013 X X Freiberger Straße 39 6 01067 Tietze Petra Dipl.-Ing. VCDB VerkehrsConsult Dresden-Berlin GmbH 2018 X X X TU Dresden, Institut für Verkehrsplanung und Straßenverkehr 7 01069 Lippold Christian Prof. Dr.-Ing. 2000 X X Hettnerstraße 1 01069 Dresden TU Dresden, Institut für Verkehrsplanung und Straßenverkehr 8 01069 Maier Reinhold Prof. Dr.-Ing. 2000 X X X Hettnerstraße 1 01069 Dresden Landeshauptstadt Dresden Straßen- und Tiefbauamt 9 01069 Schenk Martina Dipl.-Ing. 2017 x x x St. Petersburger Str. 9 01069 Dresden Landeshauptstadt Dresden Straßen- und Tiefbauamt 10 01069 Politschuk Alexander 2018 x x x St. Petersburger Str. 9 01069 Dresden Seite 1 Liste der Planungs- und Bestandsauditoren nach Postleitzahlen Stand: 23.09.2021 Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Dresden Fakultät Bauingenieurwesen 11 01069 Vesper Andreas Prof. Dr.-Ing. Professur Verkehrswesen 2018 X X X Friedrich-List-Platz 1 01069 Dresden Landesamt für Straßenbau und Verkehr 12 01099 Berger Ralf Dr.-Ing. -

Drucksache 19/32013 19

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/32013 19. Wahlperiode 13.08.2021 Vorabfassung - wird durch die lektorierte Version ersetzt. - wird durch die lektorierte Version Vorabfassung Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Oliver Luksic, Frank Sitta, Bernd Reuther, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der FDP – Drucksache 19/31605 – Die Zukunft der DEGES Vorbemerkung der Fragesteller Die Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH (DEGES) ist seit den 90er-Jahren bei Planung und Bau von Infrastrukturprojekten in Deutsch- land aktiv. Sie befindet sich heute im gemeinsamen Besitz des Bundes sowie der Länder Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Sachsen, Sachsen- Anhalt, Thüringen, Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein, Bremen, Hessen, Baden- Württemberg, Berlin und Nordrhein-Westfalen. Durch die Betreuung der Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche Einheit (VDE) sowie weiterer Großprojekte besitzt die DEGES eine hohe Fachexpertise und Spezi- alisierung in ihren Arbeitsgebieten. Die DEGES hat zudem einen erheblichen Anteil der Pilotprojekte des Bundes im Bereich Building Information Mode- ling (BIM) durchgeführt und sich in diesem Bereich eine hohe Expertise ent- wickelt. Aus diesem Grund war von Seiten des Bundes auch die Verschmel- zung mit der neuen Autobahn GmbH erörtert worden. Aufgrund verfassungs- rechtlicher und anderweitiger Hindernisse wurde dies allerdings nicht umge- setzt. Gleichzeitig überschneiden sich die Arbeitsbereiche der beiden Unter- nehmen, welche beide (zumindest teilweise) in Bundeshand sind, direkt. Da- her besteht möglicherweise eine ineffektive Dopplung von Tätigkeitsfeldern zwischen der erfahrenen DEGES und der neu formierten Autobahn GmbH. 1. Welche Prioritäten setzt die Bundesregierung in Bezug auf die unterneh- merische Ausrichtung und Zukunft sowie Schwerpunktsetzung der DEGES? 8. Bis wann rechnet die Bundesregierung mit der Verschmelzung von DEGES und Autobahn GmbH? 13. -

BIM – Status of Implementation in Germany

BIM – Status of Implementation in Germany Professor Dr. Bastian Fuchs 2017 Annual Conference of the European Society of Construction Law University of Fribourg Switzerland Building Information Modelling Status of Implementation in Germany rd November, 3 2017 Prof. Dr. Bastian Fuchs, LL.M. (San Diego) Attorney-at-Law (New York, USA) Specialist Lawyer for Construction and Architect Law, Specialist Lawyer for International Economic Law, Honorary Professor for German and International Construction Law at Bundeswehr University Munich TOPJUS Rechtsanwälte Kupferschmid & Partner Contents A. Implementation in Germany I. “Step plan of digital planning and building” II. Testing of BIM in six pilot projects III. BIM-standards IV. BIM-method in 13 rail, 10 road and one water project V. “Master plan” construction 4.0 VI. BIM professionals B. Legal aspects 2 A. Implementation in Germany Leading role in the implementation of BIM: Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure in cooperation with the “Deutsche Bahn” and the DEGES According to a decree of the Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety the suitability of the BIM-method is to be tested in building construction projects with construction costs of five million euros or more (1) ( Funding initiatives like the “BIMiD – BIM-reference project in Germany“ (2 3 A. Implementation in Germany I. “Step plan of digital planning and building” • On December 15, 2015 the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (FMTI) presented in cooperation with the “planen-bauen 4.0 GmbH” a three steps plan • Aim: making digital planning and building a nationwide standard (3) • First step plan includes the implementation of BIM for the performance level 1 Minimum requirements of performance level 1 should be met in all new planned • projects with BIM as of 2020 • Until then the public clients in the jurisdiction of the FMTI must be able to use these requirements in the (re-) tenders of planning services (4) 4 A. -

A 14 Halle – Magdeburg, Gesamtfertigstellung

Verkehrsprojekt Deutsche Einheit Nr. 14 Vierstreifiger Neubau der A 14 Magdeburg–Halle Dokumentation 2000 DEGES Neubau der A 14 Magdeburg–Halle Verkehrsprojekt Deutsche Einheit Nr.14 Dokumentation 2000 im Auftrag der Bundesrepublik Deutschland des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt und der DEGES Inhalt Zum Geleit Bundesminister für Verkehr, Bau- und Wohnungswesen . Seite 4 Historie Es begann vor 75 Jahren . Seite 6 Wechselvolle Planungsgeschichte für eine Autobahn zwischen Magdeburg und Halle . Seite 7 Neubeginn Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche Einheit – Optimierung der Infrastruktur in den neuen Bundesländern . Seite 10 DEGES – Projektmanagement für den Autobahnbau . Seite 11 Zum Geleit Minister für Wohnungswesen, Städtebau und Verkehr des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt . Seite 14 Projekt Eine wichtige Regionalverbindung für das Land Sachsen-Anhalt . Seite 16 Die Autobahn bündelt den Verkehr und entlastet die Ortsdurchfahrten . Seite 18 Die A 14 ist eine unverzichtbare Voraussetzung zur Verwirklichung der landesplanerischen Ziele . Seite 19 Variantenvergleiche – Die Suche nach der besten Lösung. Seite 20 2 Inhalt Maßnahmen Von der AS Dahlenwarsleben (L 47) bis zur AS Schönebeck (B 246 a) . Seite 22 Von der AS Schönebeck (B 246 a) bis zur AS Könnern (B 71) . Seite 27 Saalebrücke Beesedau – ein Bauwerk der Besonderheiten . Seite 30 Von der AS Könnern (B 71) bis zur AS Halle-Peißen (B 100) . Seite 36 Anschlussstelle Halle-Peißen (B 100) . Seite 39 Streckenbezogenes Gestaltungskonzept für die Brückenbauwerke . Seite 40 Umwelt Hoher Stellenwert für die Ökologie . Seite -

Und Verkehrsingenieure in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Ev

Info I/06 Vereinigung der Straßenbau- und Verkehrsingenieure in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern e.V. Sicherheit von Ingenieurbauwerken, insbesondere von Brücken in M-V ach den tragischen Ereignissen in Bad Reichenhall und Ka- Der § 836 BGB regelt ... die Haftung eines jeden Ntowice, bei denen infolge von Dacheinstürzen zahlreiche Grundstücksbesitzers ... : Tote und Verletzte zu beklagen waren, wird die Sicherheit von Bauwerken jetzt auch in der breiten Öffentlichkeit diskutiert und ird durch den Einsturz eines Gebäudes oder eines an- nicht nur bei den einfachen Bürgern, sondern auch unter den für „Wderen mit einem Grundstück verbundenen Werkes ein öffentliche Bauten zuständigen Personen macht sich teilweise Mensch getötet, der Körper oder die Gesundheit eines Menschen Verunsicherung breit. Dennoch wäre unrichtig, aus solchen Un- verletzt oder eine Sache beschädigt, so ist der Besitzer des Grund- glücksfällen auf ein generelles Standsicherheitsproblem für die stücks, sofern der Einsturz oder die Ablösung die Folge fehler- vorhandene Bausubstanz zu schlussfolgern. Fest steht aber auch, hafter Errichtung oder mangelhafter Unterhaltung ist, verpfl ichtet, dass selbst bei den sich überwiegend in öffentlicher Hand befi nd- dem Verletzten den daraus entstehenden Schaden zu ersetzen. Die lichen Ingenieurbauwerken die Verantwortung für deren sichere Ersatzpfl icht tritt nicht ein, wenn der Besitzer zum Zwecke der Errichtung, Veränderung und Nutzung sehr unterschiedlich wahr- Abwendung der Gefahr die im Verkehr erforderliche Sorgfalt be- genommen wird. achtet