262 Gran Torino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Exploitation Plan

D9.10 – Final Exploitation Plan Jorge Lpez (Atos), Alessandra Tedeschi (DBL), Julian Williams (UDUR), abio Massacci (UNITN), Raminder Ruprai (NGRID), Andreas Schmitz ( raunhofer), Emilio Lpez (URJC), Michael Pellot (TMB), Zden,a Mansfeldov. (ISASCR), Jan J/r0ens ( raunhofer) Pending of approval from the Research Executive Agency - EC Document Number D1.10 Document Title inal e5ploitation plan Version 1.0 Status inal Work Packa e WP 1 Deliverable Type Report Contractual Date of Delivery 31 .01 .20 18 Actual Date of Delivery 31.01.2018 Responsible Unit ATOS Contributors ISASCR, UNIDUR, UNITN, NGRID, DBL, URJC, raunhofer, TMB (eyword List E5ploitation, ramewor,, Preliminary, Requirements, Policy papers, Models, Methodologies, Templates, Tools, Individual plans, IPR Dissemination level PU SECONO.ICS Consortium SECONOMICS ?Socio-Economics meets SecurityA (Contract No. 28C223) is a Collaborative pro0ect) within the 7th ramewor, Programme, theme SEC-2011.E.8-1 SEC-2011.7.C-2 ICT. The consortium members are: UniversitG Degli Studi di Trento (UNITN) Pro0ect Manager: prof. abio Massacci 1 38100 Trento, Italy abio.MassacciHunitn.it www.unitn.it DEEP BLUE Srl (DBL) Contact: Alessandra Tedeschi 2 00113 Roma, Italy Alessandra.tedeschiHdblue.it www.dblue.it raunhofer -Gesellschaft zur Irderung der angewandten Contact: Prof. Jan J/r0ens 3 orschung e.V., Hansastr. 27c, 0an.0uer0ensHisst.fraunhofer.de 80E8E Munich, Germany http://www.fraunhofer.de/ UNIVERSIDAD REL JUAN CARLOS, Contact: Prof. David Rios Insua 8 Calle TulipanS/N, 28133, Mostoles david.riosHur0c.es -

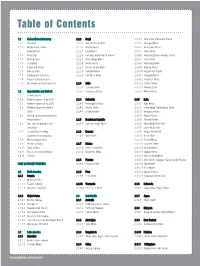

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

Newsletter Committee on Education and Issue 5

ITA-CET Committee on Education and Training |Issue 5 1 ITA-CET Newsletter Committee on Education and Issue 5 Training December 2016 IN THIS ISSUE of its dependence on foreign expertise. A rising demand for ITA training sessions Editorial Europe is also investing in innovative We take look at the sessions held over the last underground training facilities, with an year and some of the factors behind this success ambitious project underway in Austria. (page 2) Through its actions, the ITA-CET Committee contributes to identifying current training ITA training sessions in 2016: key figures requirements around the globe and providing Essential information in a nutshell (page 3) education and training opportunities to student engineers and young professionals eager to make a career in the industry. When east meets west: Austria and India cooperate to train future engineers Since our last issue in May this year, another An example of collaboration between universities 6 training sessions have been held in South across the globe (page4) America, Asia and Europe, organized in collaboration with the ITACET Foundation. The Committee has continued to expand its The Committee says farewell to a valued list of potential lecturers, with three new member additions: Senthil Nath, senior tunnel Volker Wetzig leaves his role as Activity Group engineer at Geoconsult, Bjørn Nilsen, a leader (page 4) professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Fermín Dear ITA friends, Sánchez-Reyes, associate professor at the Malaysia: training tomorrow’s manpower National University of Mexico. The Committee visits the Tunnelling Training Since the mid-2000s, there has been a major Academy near Kula Lumpur (page 5) boom in the tunnelling and underground The Committee is also pleased to welcome a space market worldwide. -

Company Profile 2019 Underground Sustainable

UNDERGROUND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS COMPANY PROFILE 2019 35 YEARS OF GROWTH 3 IstanbUL, TURKEY 6 DIFFERENT METRO LINES DESIGNED TODAY by Geodata AND UNDER constrUCTION; Gayrettepe-NEW Airport AND Kadikoy-Kartal LINES already IN operation. Snowy 2.0 HPSP, AUstralia The value and power of the water, facilitation of mobility beyond Powerchina BECOMES THE MAJOR TRANSANDINO AND MARCONA SHAREHOLDER OF Geodata GROUP 2017 Railways IN PERU barriers, reaching towards the future through cultivation of state-of-the-art engineering. A sustainable environment with OPENING OF THE BRANCHES IN BOLIVIA, EL BALA 3675 MW HPP, BOLIVIA Canada & KathmandU (Nepal) 2015 SÃO PAUlo METRO – EXTENSION OF LINE 5 which people relate. Daily challenges to improve the quality of life. Innovation continues. 400 professionals working IN THE Geodata GROUP; 2012 Flood-RELIEF TUnnels OF THE MALDONADO CONTINUING EXpansion IN matURE AND HIGH-DEMANDING RIVER IN BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA Established in 1984 in Turin (Italy), as an independent geo-engineering company. markets, USA, SINGAPOUR, TURKEY (2013) LIMA METRO LINES 2 AND 4, PERU OHSAS 18001 Certification GEODATA is leader in Italy and internationally recognized in the field of design and COMPLEMENTING worldwide rooting Starting involvement IN INDIAN METROS: engineering of underground infrastructures. (AUstralia, Colombia, PERU) 2011 Bangalore, DELHI, LUcknow, Ahmedabad, BREAKING THROUGH 40 M€ REVENUES CHENNAI, MUmbai, BOPHAL & INDOORE Still strongly focused on tunnelling and underground space use, GEODATA has gradually become a global multidisciplinary designer. ISO 14001 Certification Starting involvement IN INDIAN Railways: start working IN INDIA 2010 Sivok-RANGPO, RISHIKESH-Karanprayang, TUnnels T1-T5 ON UDHAMPUR-Srinagar-BARAMULLA GEODATA presents itself as the ideal global partner to create the positive and effective synergy RAIL LINK - T74R Railway TUNNEL with partners and clients for developing complex projects. -

CP2021 ENG.Pdf

UNDERGROUND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS COMPANY PROFILE 2021 English 3537 YEARSYEARS OF OF GROWTH GROWTH 3 ISTANBISTANBUL,uL, TuRKEY TURKEY 6 DIFFERENT 6 DIFFERENT METRO METRO LINES DESIGNED LINES DESIGNED TODAYTODAY BYBY GEODATA GEODATA AND AND uNDER UNDER CONSTR CONSTRUCTION;uCTION; GAYRETTEPE- GNEWAYRETTEPE-NEW AIRPORT AND AIRPORT KADIKOY-KARTAL AND KADIKOY-KARTAL LINES LINESALREADY IN The value and power of the water, facilitation of mobility beyond ALREADYOPERATION. IN OPERATION. SNOWY SNOWY2.0 HPSP, 2.0 HPSP,AUSTRALIA AuSTRALIA The value and power of the water, facilitation of mobility beyond barriers, reaching towards the future through cultivation of POWERCHINAPOWERCHINA BECOMES BECOMES THE THE MAJOR MAjOR TRANSANDINO AND MARCONA 2017 RAILWAYSTRASANDINO IN PERu AND MARCONA RAILWAYS IN PERU barriers, reaching towards the future through cultivation of SHAREHOLDERSHAREHOLDER OF OF GEODATA GEODATA GROUP GROuP state-of-the-art engineering. A sustainable environment with state-of-the-art engineering. A sustainable environment with which people relate. Daily challenges to improve the quality of life. OPENINGOPENING OF OFTHE THE BRANCHES BRANCHES IN IN BOLIVIA, BOLIVIA, ELEL BALA BALA 3200 3200 MW MW HPP, HPP, BOLIVIA BOLIVIA 2015 SãO PAuLO METRO – ExTENSION OF LINE 5 which people relate. Daily challenges to improve the quality of life. CANADACANADA & KATHMANDU& KATHMANDu (NEPAL (NEPAL)) 2015 SÃO PAULO METRO – EXTENSION OF LINE 5 Innovation continues. Innovation continues. 400400 PROFESSIONALS PROFESSIONALS WORKING WORKING IN THE IN GEODATATHE GEODATA GROuP; 2012 FLOOD-RELIEFFLOOD-RELIEF TuNNELS TUNNELS OF OF THE THE MALDONADO MALDONADO RIVER IN CGROUP;ONTINuING CONTINUINGExPANSION IN EXPANSIONMATuRE AND IN HIGH MATURE-DEMANDING AND RIVERBUENOS IN BuENOS AIRES, AIRES,ARGENTINA ARGENTINA EstablishedEstablished in in 19841984 inin TurinTurin (Italy), as anan independentindependent geo-engineeringgeo-engineering company. -

Activity Report 2019 Activity Reports 2019 ITA Is the Leading International Organization for 4 Albania Tunnelling and Underground Space

ITA MEMBER NATION ACTIVITY REPORTS 2019 ITA MEMBER NATION MEMBER NATION ITA September 2020 ACTIVITY REPORTS 2019 ITA Member Nation Activity Reports 2019 1 20-08-18_011_ID20081_eAz_Brenner_ITA Activity Report_210x297_RZgp ITA MEMBER NATION ACTIVITY REPORTS 2019 BRENNER BASE TUNNEL, AUSTRIA – ITALY PUSHING LIMITS WITH VIGOROUS ENGINEERING The new brenner base tunnel represents a next level of trail blazing hard-rock-tunnelling. With a total length of 64 km and maximum overburdenHERRENKNECHT of 1,300 meters this high-impact project AD sets new records. Six project specific engineered Herrenknecht hard-rock-machines are involved in the hardest mission worldwide. Empowering our customers to push the limits. herrenknecht.com/bbt/ Contractors: 1 x Gripper TBM: Consortium H33 Tulfes-Pfons 3 x Double Shield TBM: Consortium Mules 2-3 2 x Single Shield TBM: Consortium H51 Pfons-Brenner 2 20-08-18_011_ID20081_eAz_Brenner_ITA Activity Report_210x297_RZgp.indd 1 18.08.20 10:34 ITA MEMBER NATION ACTIVITY REPORTS 2019 Contents Jinxiu (Jenny) Yan ITA President ITA President’s message for the ITA ITA MEMBER NATION Member Nations Activity Report 2019 Activity Reports 2019 ITA is the leading international organization for 4 Albania tunnelling and underground space. This position is dependent not only on the intensive worldwide 5 Argentina activities of the ITA itself, but also of its Member 6 Australia Nations with their leading positions in their respective countries. Over the past year, this has 9 Belarus been further consolidated via stronger communication and closer cooperation 10 Brazil between the ITA and its Member Nations, and also among the Member Nations 13 Bulgaria themselves. Issuing this print version of the yearly ITA Member Nations Activity report is one 13 Canada of the most effective ways to promote better communications within the ITA HERRENKNECHT AD 16 Chile family. -

World's Best Driverless Metro Lines 2017

WORLD’S BEST DRIVERLESS METRO LINES 2017 MARKET STUDY ON DRIVERLESS METRO LINES AND BENCHMARK OF NETWORK PERFORMANCE www.wavestone.com Wavestone is a consulting firm, created from the merger of Solucom and Kurt Salmon’s European Business (excluding retails and consumer goods outside of France) Wavestone’s mission is to enlighten and guide their clients in the most critical decisions, drawing on functional, sectoral and technological expertise. 2 Foreword In tomorrow’s megacities, citizens’ megacities which are coming into view selected route will take on increasing in emerging countries in Asia, Africa and importance (in France, journey length South America as well as the challenges grew by 63% between 1982 and 2008 presented by the peripheral urbanization according to INSEE, France’s National of highly dense big cities in developed Institute of Statistics and Economic European countries. Studies). This panorama on “smartization”, which At the same time, citizens’ habits regard- optimizes and streamlines urban mobil- ing transport change as a result of pres- ity highlights France as the flagship of sure, from environmental responsibility driverless metro system operations. The which is more present in their conscience momentum of its authorities and industry and, on the other hand, from congestion in the segment has propelled the country in city centers. The “transport mix” in big to the top of the pack in the global driv- cities has clearly shifted from the individ- erless metro market. ual car towards mass public transport. A transport system’s performance is based Faced with the challenge of transporting on strategic choices made over the long more passengers in a continuous and fluid term by the organizing transport authority way, and with the challenge of increasing and tactical and operating choices made line capacity that is already saturated, the by the operator. -

List of Track Gauges Wikipedia List of Track Gauges from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/13/2017 List of track gauges Wikipedia List of track gauges From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This list presents an overview of railway track gauges by size. A gauge is measured between the inner faces of the rails. Contents 1 Track gauges by size 1.1 Minimum and ridable miniature railways 1.2 Narrow gauge 1 1.3 Standard gauge: 1,435 mm / 4 ft 8 ∕2 in 1.4 Broad gauge 2 See also 3 References 4 External links Track gauges by size Minimum and ridable miniature railways For ridable miniature railways and minimum gauge railways, the gauges are overlapping. There are also some extreme narrow gauge railways listed. See: Distinction between a ridable miniature railway and a minimum gauge railway for clarification. Model railway gauges are covered in rail transport modelling scales. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_track_gauges 1/14 2/13/2017 List of track gauges Wikipedia Gauge Country Notes Metric Imperial 1 1 89 mm 3 ∕2 in See 3 ∕2 in (89 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 3 3 121 mm 4 ∕4 in See 4 ∕4 in (121 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 127 mm 5 in See 5 in (127 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 1 1 184 mm 7 ∕4 in See 7 ∕4 (184 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 1 1 190.5 mm 7 ∕2 in See 7 ∕2 in (190.5 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 1 1 210 mm 8 ∕4 in See 8 ∕4 in (210 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways See 9 in (229 mm) gauge ridable miniature railways 229 mm 9 in Railway built by minimum gauge pioneer Sir Arthur Heywood, later England abandoned in favor of 15 in (381 mm) gauge. -

URBAN RAIL CAPABILITIES London Tramlink: Special 20-Page Review

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Toronto council takes key LRT vote l Bombardier close to 775-car BART order l Alstom demonstrates Citadis in Moscow SIEMENS BOLSTERS GLOBAL URBAN RAIL CAPABILITIES London Tramlink: Special 20-page review The end for paper? Driver safety: Easier for riders, Latest research better for operators: on managing 75 Smart ticketing driver risk for systems explained safer systems MAY 2012 No. 893 1937–2012 WWW. LRTA . ORG l WWW. TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 TAUT_April12_Cover.indd 1 3/4/12 12:12:59 XX_TAUT1205_UITPAD.indd 1 2/4/12 09:58:22 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 168 News 168 MAY 2012 Vol. 75 No. 893 Toronto light rail supporters win key vote; Siemens www.tramnews.net announces global expansion ambitions; Alstom EDITORIAL demonstrates its Citadis tram in Moscow; Bombardier Editor: Simon Johnston preferred bidder for USD3.4bn, 775-car BART order. Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. 174 Smart ticketing technologies Associate Editor: Tony Streeter John Austin examines the strategies operators can and are E-mail: [email protected] employing to drive ridership – and looks to the future. Worldwide Editor: Michael Taplin 174 Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. 179 Creating safer journeys E-mail: [email protected] Dr Lisa Dorn explains how detailed research is shaping News Editor: John Symons tram driver employment and training regimes. 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. Systems Factfile: Valencia E-mail: [email protected] 183 Contributor: Neil Pulling Introducing modern trams to Spain was just one part of a project to drastically restructure public transport in its Design: Debbie Nolan third-largest city. -

Read Italy Activity Report

ITA MEMBER NATION ACTIVITY REPORTS 2019 The association members take part in the ITA-AITES working group (WGs) and Italy in the SIG working groups. Members proactively collaborate with national and Name: Società Italiana Gallerie (Italian Tunnelling international colleagues to exchange Society) expertise and experience, divulging technical, scientific and business know Type of Structure: Scientific, non-profit how in underground construction. SIG Number of Members: About 800 members (inc. 80 corporate members) WG “Research” published in May 2019 the guideline on “Damages of segmental lining”. A free copy can be downloaded ASSOCIATION ACTIVITIES DURING Milano and of the Level II Masters from the SIG website. 2019 AND TO DATE in Geotechnical engineering at the The SIG YM Group, with 180 young Congress Sapienza University in Rome and at the tunnellers as of December 2019, actively 03-09/05/2019 World Tunnel Congress, Federico II University in Naples. These supports SIG activities and connects Naples: Tunnels and Underground collaborations aim to bridge the gap young professionals from both University Cities: Engineering and Innovation meet between Universities and Industry and and Industry. The group has also Archaeology, Architecture and Art, to support the growth of future industry established a fruitful collaboration with Naples leaders. the other ITA Member Nation YM Groups. 03/12/2019 S. Barbara Congress & Since 1976, the Journal “Tunnels and SIG has also published, in May 2019, Adolfo Colombo Lecture: L’ingegneria e Major Underground Works” is SIG’s the booklet “The Italian Art of Tunnelling l’imprenditoria italiana del secolo scorso: pride and glory. It is currently published 2019” collecting statistics on existing tra scienza, tecnica ed emozioni, Milan once every three months and it reached Italian tunnels and technical sheets issue 132 in December 2019. -

Word Template for Authors

UNWTO/WTCF City Tourism Performance Research Report for Case Study: “Turin, Italy” Note: This document is a working paper Map of Turin, in Piedmont Region of Italy Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... i Foreword ................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ................................................................................................ iii 1. Background information on Turin and its development over past 25 years ... 1 1.1 Location – advantages and disadvantages ....................................................... 1 1.2 History ............................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Turin reinventing itself – the Phoenix rises ........................................................ 4 2. Tourism in Turin ................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Primary tourism attractions of Turin – overview ................................................ 7 2.2. Performance Data .......................................................................................... 11 3. Strategic planning and development of Turin since 1990 .............................. 18 3.1 City Development Plans and their key proposals for enhancing the city environment, economy, infrastructure and tourism .............................................. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

GLOBALGLOBAL METROMETRO RAILRAIL PROJECTSPROJECTS REPORT:REPORT: MARKETMARKET ANDAND INVESTMENTINVESTMENT OUTLOOKOUTLOOK 2020-20302020-2030 Global Mass Transit Research has just launched the fifth edition of the Global Metro Rail Projects Report: Market and Investment Outlook 2020-22030, the most comprehensive and up- to-date study on the metro rail segment. The report will provide information on the top 150 metro rail projects in the world in terms of upcoming investments and plans. It will provide details on the existing network, stations, ridership, rolling stock, technology and fare systems. It will highlight upcoming capital investment needs and opportunities such as construc- tion of new lines and extensions, upgrades of existing lines, procurement and refurbishment of rolling stock, upgrades of power and communication systems, upgrades of fare collec- tion systems, as well as construction and refurbishment of stations. The report will comprise two distinct sections. Part 1 of the report (PPT format converted to PDF) will describe the existing state of, and - Current ridership the expected opportunities in, the global metro rail industry in terms of network and sta- - Current rolling stock (number of rail cars, technology, suppliers, age, etc.) tion construction and development, ridership, rolling stock, signalling, fare system, power, - Existing signalling system (type of system, suppliers, etc.) tracks, consulting, etc. It will examine the recent technical and financing developments; - Power and tracks analyse key growth drivers and challenges; and assess the upcoming opportunities and - Current fare system (type of system, ticketing infrastructure, suppliers, etc.) future outlook for the industry. - Extensions/ Capital projects - upcoming network and stations - Planned investments, cost estimates and funding Part 2 of the report (MS Word converted to PDF) will provide updated information on 150 - Projected ridership projects that present significant capital investment opportunities.