21St CENTURY LANGUAGE POLICY in JAMAICA and TRINIDAD AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trini Talk Or the Queen's English?

Copyright by Sarojani S. Mohammed 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Sarojani S. Mohammed Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Trini Talk or the Queen’s English? Navigating Language Varieties in the Post-Colonial, High Stakes Climate of “Standard Five” Classrooms in Trinidad Committee: Diane L. Schallert, Co-Supervisor Barbara G. Dodd, Co-Supervisor Lars Hinrichs Zena T. Moore Marilla D. Svinicki Brandon K. Vaughn Trini Talk or the Queen’s English? Navigating Language Varieties in the Post-Colonial, High Stakes Climate of “Standard Five” Classrooms in Trinidad by Sarojani S. Mohammed, S.B. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2008 Dedication To the newest source of inspiration in my life, my nephew, Henrik Åge Lundgård. Acknowledgements In many ways, this document represents the love and support of the village that raised me. I regret that I cannot express my gratitude to every person who has helped me along the way, but I appreciate this opportunity to acknowledge in print those who have devoted inordinate amounts of time and effort to ensure the completion of this degree, and this project in particular. To my parents, who knew that I could do this even before it was a dream of mine, I thank you for your love and patience, help and advice, and especially for your encouragement and support over the past 27 years. To my brother and sister, thanks for making me who I am, and loving me as I am. -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

Earlier Caribbean English and Creole in Writing Bettina M Migge, Susanne Muehleisen

Earlier Caribbean English and Creole in Writing Bettina M Migge, Susanne Muehleisen, To cite this version: Bettina M Migge, Susanne Muehleisen,. Earlier Caribbean English and Creole in Writing. Hickey, Raymond. Varieties in writing: The written word as linguistic evidence, John Benjamins, pp.223-244, 2010. halshs-00674699 HAL Id: halshs-00674699 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00674699 Submitted on 28 Feb 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Earlier Caribbean English and Creole in writing Bettina Migge Susanne Mühleisen University College Dublin University of Bayreuth Abstract In research on Creoles, historical written texts have in recent decades been fruitfully employed to shed light on the diachronic development of these languages and the nature of Creole genesis. They have so far been much less frequently used to derive social information about these communities and to improve our understanding of the sociolinguistics and stylistic structure of these languages. This paper surveys linguistic research on early written texts in the anglophone Caribbean and takes a critical look at the theories and methods employed to study these texts. It emphases the sociolinguistic value of the texts and provides some exemplary analyses of early Creole documents. -

Language and Country List

CONTENT LANGUAGE & COUNTRY LIST Languages by countries World map (source: United States. United Nations. [ online] no dated. [cited July 2007] Available from: www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm) Multicultural Clinical Support Resource Language & country list Country Languages (official/national languages in bold) Country Languages (official/national languages in bold) Afghanistan Dari, Pashto, Parsi-Dari, Tatar, Farsi, Hazaragi Brunei Malay, English, Chinese, other minority languages Albania Tosk, Albanian Bulgaria Bulgarian, Turkish, Roma and other minority languages Algeria Arabic, French, Berber dialects Burkina Faso French, native African (Sudanic) languages 90% Andorra Catalán, French, Spanish, Portuguese Burundi Kirundi, French, Swahili, Rwanda Angola Portuguese, Koongo, Mbundu, Chokwe, Mbunda, Cambodia Khmer, French, English Antigua and English, local dialects, Arabic, Portuguese Cameroon French, English, 24 African language groups Barbuda Canada English, French, other minority languages Argentina Spanish, English, Italian, German, French Cape Verde Portuguese, Kabuverdianu, Criuolo Armenia Armenian, Yezidi, Russian Central French (official), Sangho (lingua franca, national), other minority Australia English, Indigenous and other minority languages African languages Austria German, Slovenian, Croatian, Hungarian, Republic Alemannisch, Bavarian, Sinte Romani, Walser Chad French, Arabic, Sara, more than 120 languages and dialects Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri), Russian, Armenian, other and minority languages Chile -

Variation Theory: a View from Creole Continua

Variation Theory: a View from Creole Continua DONALD WINFORD Department of Linguistics The Ohio State Uiiiversity 1712 Neil Avenue. Colunibus OH 432 10. USA [email protected] ABSTRACT P~.ac.tictioner.s of tlie CI~~LI(?f 1ingui.stic ini.e,stieation ~.<ferredto as 'quantirarii~e' 01. 'in~.iarionist'sociolinguisric~.~ gener~lll? sec. tlleir objrctii,e ea heing to rrncoivr mid rrt.c.owit.fii/. tlze q3.srrriiatici~~cndet.l?ing \m-iation in speecll bellaiior. To rlzis end. rliq 1ioi.e emply,ed ci i,rlrieg c?frriotlioclsas it'e11 c1.s ancrlytic 17zodel.v aitried at incorporating i~erricrhiliginto 1ingui.rtic descriprion. Among rlze approaches o/-e Lahoi,'s 'vririahle rule' ~nodel.and Bickerton S 'inll>lic.ariond'~~ioclel. Tlie ]>re.senrpclper e~xarninesthe rrlei~arrc~c!f rllese rriode1.s of ibclrirltiotl ro Crlrihhccnl E~rglislzcreole conrinicci clnd roncludes rlzur neirlin. i.r itlrll suited to proiiding a ~clrisjkrro~]~accounr ?fthe sociolingui.sric hererogeneih. clinrcicreri.stic of s~rcllsirlrariori.~. Like orller ,s]>eec.licommunirie.~, C~irihhean ci-eole continua tncirijfest prlrrerns of sociul and .sgli.stic di'erentiation of linguistic clioices. But, urilike t\pical dialecr siruations, [he? disj~l~slzarp irltenial drfferences in linguistic repertoire.~cind relarionsliil>sivhicli e-onnor he .suh.sumed under a .single giuitimar. T~c,f¿iiluw of ~arirrrionisrrheot?. ro adequorel~.~lescrihe ílze order-1). hetrrogeiieir\. of such continuo 110s to (lo jifi,.sr, irlith the crrchitecture qTrlze proposed models, cnid .sec,orld. ivith its tendenr? fo ft-eclt .sociolinguistic plienor7lenri (1,s rliougll tlle!, c,ould hr tmlslared directly into gra/n/nri,ir. -

Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. dr. S. Kouwenberg (University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica) Prof. dr. C.H.M. Versteegh Part of the research reported in this dissertation was funded by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (KNAW). i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS ix 1. VARIATION IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE: TENSE-ASPECT- MODALITY 1 1.1. -

Pidgin and Creole Languages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke

Pidgin and Creole Languages JOHN E. REINECKE 1904–1982 Pidgin and Creole Languages Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke Edited by Glenn G. Gilbert Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882150 (PDF) 9780824882143 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1987 University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Preface viii Acknowledgments xii Introduction 1 John E. Reinecke: His Life and Work Charlene J. Sato and Aiko T. Reinecke 3 William Greenfield, A Neglected Pioneer Creolist John E. Reinecke 28 Theoretical Perspectives 39 Some Possible African Creoles: A Pilot Study M. Lionel Bender 41 Pidgin Hawaiian Derek Bickerton and William H. Wilson 65 The Substance of Creole Studies: A Reappraisal Lawrence D. Carrington 83 Verb Fronting in Creole: Transmission or Bioprogram? Chris Corne 102 The Need for a Multidimensional Model Robert B. Le Page 125 Decreolization Paths for Guyanese Singular Pronouns John R. -

Agreement in Educated Jamaican English: a Corpus Investigation of ICE-Jamaica

Agreement in Educated Jamaican English: A Corpus Investigation of ICE-Jamaica Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philologischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Susanne Jantos aus Räckelwitz SS 2009 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Christian Mair Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernd Kortmann Vorsitzende des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Cheauré Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 09.11.2009 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................1 2 Background to the Study ............................................................................................4 2.1 The Jamaican Language Situation......................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Historical Development of the Language Situation in Jamaica ....................5 2.1.2 New Englishes – Classification and Development......................................12 2.1.3 Linguistic Variation in New Englishes and Underlying Principles.............20 2.2 Linguistic Variation in Jamaica...........................................................................23 2.2.1 The Creole Continuum ................................................................................ 23 2.2.2 Morphosyntactic Characteristics of Jamaican English................................27 3 Previous Research -

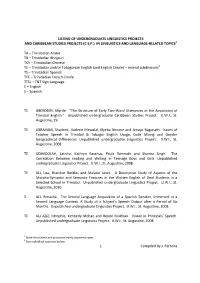

Compiled by J. Ferreira 1 LISTING OF

LISTING OF UNDERGRADUATE LINGUISTICS PROJECTS AND CARIBBEAN STUDIES PROJECTS (C.S.P.) IN LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE-RELATED TOPICS 1 TA – Trinidadian Arabic TB – Trinidadian Bhojpuri TCh – Trinidadian Chinese TE – Trinidadian and/or Tobagonian English (and English Creole) – several subdivisions 2 TS – Trinidadian Spanish TFC – Trinidadian French Creole TTSL – T&T Sign Language E – English S – Spanish TE ABERDEEN, Myrtle. “The Structure of Early Two-Word Utterances in the Acquisition of Trinidad English.” Unpublished undergraduate Caribbean Studies Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 19. TE ABRAHAM, Shadeed, Varlene Mewalal, Klyeba Nicome and Jenaya Ragunath. Issues of Teacher Speech in Trinidad & Tobago: English Usage, Code Mixing and Gender Geographical Differences. Unpublished undergraduate Linguistics Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 2008. TE ADIMOOLAH, Latisha, Kathryn Bacchus, Paula Ramnath and Shanira Singh. The Correlation Between reading and Writing in Teenage Boys and Girls. Unpublished undergraduate Linguistics Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 2008. TE ALI, Lisa, Brandon Beckles and Malarie Lewis. A Descriptive Study of Aspects of the Morpho-Syntactic and Semantic Features in the Written English of Deaf Students in a Selected School in Trinidad. Unpublished undergraduate Linguistics Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 2010. S ALI, Renasha. The Second Language Acquisition of a Spanish Speaker, Immersed in a Second Language Context. A Study of a Subject’s Speech Output after a Period of Six Months. Unpublished undergraduate Linguistics Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 2008. TE ALI AZIZ, Istrophle, Kimberly Mohan and Renee Mulchan. Power in Principals’ Speech. Unpublished undergraduate Linguistics Project. U.W.I., St. Augustine, 2008. 1 Note that these are produced every academic year. -

The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages

DigitalResources SIL eBook 25 ® The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook SIL International ® 2012 SIL e-Books 25 2012 SIL International ® ISBN: 978-1-55671-268-5 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair-Use Policy: Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor George Huttar Volume Editor Dirk Kievit Managing Editor Bonnie Brown Compositor Margaret González Abstract This study examines the four English-lexifier creole languages spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago. These languages are classified using a comparison of some of the markers of key grammatical features identified as being typical of pidgin and creole languages. The classification is based on a scoring system that takes into account the potential problems in translation due to differences in the mapping of semantic notions. -

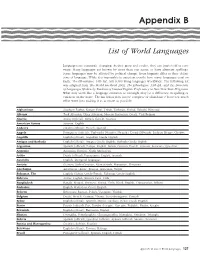

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

Teacher Language in Trinidad: a Pilot Corpus Study of Direct and Indirect Creolisms in the Verb Phrase1

Teacher Language in Trinidad: A Pilot Corpus Study of Direct and Indirect Creolisms in the Verb Phrase1 Dagmar Deuber2 and Valerie Youssef3 1. Introduction Recent work on language use in Trinidad and Tobago (Youssef, 2004) indicates the emergence of a local standard variety of English alongside the English-based Creole spoken in the country. However, no systematic research into the features of this variety has as yet been undertaken. Another change in the language situation which deserves more attention is the increasing acceptance of Creole in schools and other public contexts (cf. e.g. Youssef and James, 2004: 513). A new corpus of teacher language currently being compiled at the University of the West Indies in St. Augustine as part of a larger corpus of English in Trinidad and Tobago will provide a basis for detailed investigations of the actual language use of speakers who are important models for the generation currently growing up in the country. The teachers were recorded in the classroom and in conversations of a mostly semi-formal type – contexts which favour the use of English though a certain amount of Creole use is also to be expected (cf. also Mühleisen, 2001). The present paper reports first findings from a subset of the teacher data (this subset comprises only data from Trinidad). It is exploratory in nature and aims primarily to show the potential of a digitized spoken language corpus in research on teacher language in Trinidad and, beyond that, on the use of English and Creole influence on it in the country more generally. This will also have implications for the larger Caribbean context, where corpus-based analyses have so far been limited to Jamaican English (Sand, 1999; Mair, 2002, 2007).