Kobe University Repository : Kernel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

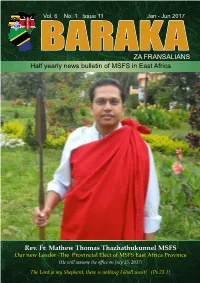

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda

Sub–Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program The World Bank and Economic Commission for Africa SSATP Working Paper No 12 Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda Christina Malmberg Calvo February 1994 Environmentally Sustainable Development Division Africa Region The World Bank Foreword One of the objectives of the Rural Travel and Transport Project (RTTP) is to recommend approaches for improving rural transport, including the adoption of intermediate transport technologies to facilitate goods movement and increase personal mobility. For this purpose, comprehensive village-level travel and transport surveys (VLTTS) and associated case studies have been carried out. The case studies focus on the role of intermediate means of transport (IMT) in improving mobility and the role of transport in women's daily lives. The present divisional working paper is the second in a series reporting on the VLTTS. The first working paper focussed on travel to meet domestic needs (for water, firewood, and food processing needs), and on the impact on women of the provision of such facilities as water supply, woodlots, fuel efficient stoves and grinding mills. The present case study documents the use of bicycles in eastern Uganda where they are a means of generating income for rural traders and for urban poor who work as bicycle taxi-riders. It also assesses women's priorities regarding interventions to improve mobility and access, and the potential for greater use of bicycles by rural women and for women's activities. The bicycle is the most common IMT in SSA, and it is used to improve the efficiency of productive tasks, and to serve as a link between farms and villages, nearby road networks, and market towns. -

Monolingualism Via Multilingualism: a Case Study of Language Use in the West Ugandan Town of Hoima

African Study Monographs, 34 (1): 1–25, March 2013 1 MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: A CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE USE IN THE WEST UGANDAN TOWN OF HOIMA Shigeki KAJI Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Multilingualism is one of the most salient features of language use in Africa and, at first sight, Uganda appears to be just one example of this practice. However, as Uganda has no lingua franca that is widely used by its entire population, questions about how people cope with multilingualism arise. Answers to such questions can be found in the fact that people are able to create a monolingual state in a given area because everyone is multilingual. That is, people speak their own language in their own domain and speak other peoples’ languages when they go to the latter’s domains. This conclusion emerged from interviews conducted with 100 inhabitants of Hoima city in western Uganda, an area primarily inhabited by the Nyoro people. The linguistic situation in Hoima provides a valuable case study of what can happen in the absence of a fully developed lingua franca and can contribute to broader discussions of language use in Africa. Key Words: Lingua franca; Multilingualism; Hoima; Nyoro; Uganda. INTRODUCTION I have conducted linguistic research in Uganda since 2001. The main themes of my research relate to the grammatical and lexical characteristics of little-known languages in the area. In the course of research, however, I noticed differences between the use of language in Uganda and that in the regions where I had studied before. -

Kasujja EDU ARTICLE 2012

Ethnocentrism and National Elections in Uganda John Paul Kasujja, Anthony Muwagga Mugagga The paper focuses on ethnocentrism as an active factor for national election turmoil in Uganda. The bewitchment of the military by ethnocentric virus, the subsequent coups and overthrows, to the military regimes and dictatorships by successive presidents since 1966, the 1980, 1996, 2001 and 2006 presidential elections, can account for ethnocentric tendencies in the Pearl of Africa. Thereafter, the paper discusses the 1996, 2001 and 2006 general elections held in Uganda before propounding implications for the country’s future. Keywords : Ethnocentrism, Politics and development, Elections Introduction Uganda is in the easterly region of the African continent with a diverse ethnic composition. It borders Kenya in the East, Democratic republic of Congo in the west, Southern Sudan in the north and Tanzania in the south, Ssekamwa (1994). The area has attracted almost every ethnic group for settlement and business, and this has sensitized ethnocentrism among the settlers. This trait has been practiced in the politics of the state especially in national elections. Ethnocentrism exists in most countries across borders, but how it affects the political endeavours of a state with multi-ethnic populations vary. For the case of Uganda, ethnic differences make a significant impact on political activity, like national elections. The awareness of these differences has been referred to as “tribalism”, or ethnicity. The term ethnocentrism is a commonly used word in circles where ethnicity, inter ethnic relations and similar social issues are of concern. Its definition is “thinking one’s, group’s ways as superior to others”, or “judging other groups as inferior to one’s own”, K. -

La Diffusion Des Plantes Américaines Dans La Région Des Grands Lacs

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 52 | 2019 La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs Approches générale et sous-régionale, l’Ouest kényan Dissemination of the American Plants in the Great Lakes Region: General and Sub-Regional Approaches, the Western Kenya Elizabeth Vignati et Christian Thibon (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/452 Éditeur IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 mars 2019 ISSN : 2071-7245 Référence électronique Elizabeth Vignati et Christian Thibon (dir.), Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review, 52 | 2019, « La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 07 mai 2019, consulté le 25 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/452 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs Approches générale et sous-régionale, l’Ouest kényan Dissemination of the American Plants in the Great Lakes Region General and Sub-Regional Approaches, the Western Kenya 2019 © IFRA 2019 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de 1’Est / The East African Review n° 52, 2019 Chief Editor: Marie-Aude Fouéré Deputy Director: Chloé Josse-Durand Guest Editor: Elizabeth Vignati Editorial secretary: Bastien Miraucourt Cartographer: Valérie Alfaurt Avis L’IFRA n’est pas responsable des prises de position des auteurs. L’objectif des Cahiers est de diffuser des informations sur des travaux de recherche ou documents, sur lesquels le lecteur exercera son esprit critique. -

Abuses of Power in Traditional Practices of Acknowledgement in Uganda1

Power to the People? Abuses of power in traditional practices of acknowledgement in Uganda1 Joanna R. Quinn2 Traditional practices of acknowledgement in Uganda, as a means of bringing about the resolution of conflict and the rebuilding of society, are ostensibly used by and for the people. The literature has tended to view these practices as being an appealing, community-based alternative to other practices of transitional justice that are often top-down and far-removed from the opinions, activities, and values of the community. Yet traditional practices are sometimes carried out by individuals who, although at first glance, appear to be the justifiable wielders of power, may, in fact, be abusing this power. What follows is an exploration of the power dynamics at play behind and within these traditional practices of acknowledgement and justice in Uganda. This work is part of an exploration of the importance and utility of customary law within a framework of transitional justice. It is driven, in large part, by irregularities I have encountered in my work in Uganda, and by a desire to think through just what these abuses might mean within a larger context of transitional justice. Methodology As part of a larger, on-going study, I have been engaged since 2004 in an examination and analysis of the use of traditional practices of acknowledgement and justice in Uganda. I am specifically interested in the role that these processes play in a society’s acknowledgement of past crimes and abuses. And how they are able to succeed where other “Western” approaches, like the truth commission, have failed.3 This paper is based on seven “waves” of research that I have collected around the role of traditional practices of justice and acknowledgement in Uganda. -

REPORT STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT REPORT OF STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND PARTICIPATION IN CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLANNING PROJECT NO: P123204 CONTRACT NO: MWE/CONS/14-15/00114/2 AWOJA, MPOLOGOMA AND VICTORIA NILE CATCHMENTS Submitted to MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE OF WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT August 2017 1 Acknowledgements We acknowledge the support from Ministry of Water and Environment - Directorate of Water Resource Management and Kyoga Water Management Zone during the implementation of this activity. Our deepest thanks go to the District and sub county Local Government officials in Mpologoma, Awoja and Victoria Nile for the guidance during the selection of Sub Counties for the study. Community members are special because they voiced issues pertaining to Integrated Water Resources Management during community meetings and Focus Group Discussions. The communities shared their experiences and provided useful insites during the catchment planning process. Sub County Technical, political and Administrative leaders played a great role by mobilising the community to participate in the CMP process. IIRR would like to recognize the individual efforts and guidance provided by Commissioner-DWRM, Contract manager for this assignment, Team leader KWMZ and Technical Advisor Kyoga Water Management Zone (KWMZ) and BRLi team. Others include; Country Director-IIRR, Programs Director- IIRR, Water Resources Specialist-IIRR and all the Project officers and many others not mentioned here. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices Of

Tradition?! Traditional cultural institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda1 Joanna R. Quinn2 Working paper. Please do not cite without permission. Transitional justice is concerned with how societies move from conflict to peace or from authoritarian regimes to democracy—by dealing with the resulting questions of justice and social healing. Among the “tools” that theorists and practitioners of transitional justice have at their disposal in restoring social cohesion after conflict are customary methods of acknowledgement. While such practices have not yet become part of the mainstream, in as much as truth commissions and tribunals have, evidence of their utility in several societies is beginning to appear. The use of these traditional practices of acknowledgement in Uganda is widespread. Each of the 56 different ethnic groups across the country has at some point relied on such practices. This paper explores the attitudes of the leaders of the newly-restored traditional cultural institutions toward these practices. It further assesses the agency of traditional cultural institutions in their use. This analysis is carried out in the context of the ever-turbulent political situation in Uganda, and of the sordid legacy of conflict in that country. 1 A paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, 16 Feb. 2009, New York, USA. Research for this project was carried out with assistance from the United States Institute of Peace (SG-135-05F), with research assistance from Stéphanie Anne-Gaëlle Vieille. 2 Joanna R. Quinn is Assistant Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of the Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict Research Group at The University of Western Ontario. -

Dholuo Grammar for Beginners

DHOLUO GRAMMAR FOR BEGINNERS Peter Onyango Onyoyo 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This book is the fruit of a lot of research work from various reliable sources. I consider it a duty to express my gratitude to all who have cooperated in this work. Dholuo Grammar has been neglected for so long by many authors. I think that now is the right moment for the Luo people to study their language and to give it its true scientific meaning. Here I thank Rev. Jacob Ndong’a who did a good job to control the grammatical techniques. His contribution was very useful. Brother Martin Sadia and Benedict Ngala are both Dholuo speakers of high value. They offered their necessary contribution to this work. I can not forget the generosity of Sister Jane Akello who dedicated her time to go through the draft papers. I also express my gratitude to those who in one way or another have made this work possible. 2 This is an integrated grammar book of Dholuo language, with explanations in English. It will be handy for whoever likes to speak the language. Dholuo is the ethnic language that is spoken by the Luo people living around Lake Victoria (Sango) in the Western part of Kenya. From their original background, this ethnic group is known as the River-Lake Nilot. The linguistic root is therefore Nilotic. The Luo people usually lived around Lakes or rivers where fishing is possible. The region was known as Kavirondo from the Kavirondo gulf of Lake Victoria. From history we know that this tribal group immigrated from the Southern part of Sudan in the early Medieval period and travelled along the river Nile then settled around Lake Victoria. -

International Conference on Bride Price

International Conference On Bride Price 16th – 18th February, 2004 Held at Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Conference Report Box 274 Tororo, Uganda Email: [email protected] www.mifumi.org - 1 - Contents Acknowledgements Page 4 Conference Report Conference Keynote addresses: Dorothee Hutter Opening Remarks Page 9 Atuki Turner Bride Price Campaign Page 10 Lynda St. Cook Speech from British High Commission Page 17 Hon. Miria R.K. Matembe Relationship Between Domestic Violence and Bride Price Page 18 Dr. Sylvia Tamale Women’s Sexuality as a Site of Control & Resistance: Page 23 Views on the African Context Noerine Kaleeba Multiple Vulnerabilities drawing on statistics from around Page 38 the world on HIV/AIDS Dr. Dan Kaye Bride Price and Health Page 43 Margaret Oguli Oumo Bride Price and violence against Women: the case of Uganda Page 47 Wambui Otieno Mbugua Author of "Mau Mau's daughter - a life history" Page 52 Jane Frances Kuka Gender Violence and Female Genital Mutilation in Uganda Page 56 Mrs. Margaret Sekaggya Analysis of Bride Price from a human rights Perspective Page 59 Conference Papers: Hameed Agberemi Interrogating Hetero-Reality In Muslim Marriage Page 64 From Islamic And Human Rights Perspectives Alupo Josephine Bride Price And Gender Violence Page 94 Magdalene Bukya Bubi Bride Price And Fight Against HIV/AIDS Page 99 Mrs. Emmie Chanika Bride Price: The Case For Malawi Page 101 Alice Dokoria Coalition And Action To Safeguard The Child Page 102 Fr. Deo Eriot Religious And Cultural Perspectives On Bride Price Page 103 Benda Gard N. Bride Price And Domestic Violence Page 106 Renée Jeftha Lobola And Gender Violence Page 115 Asma’u Joda Some Thoughts About Bride Price Page 121 Tinyade Kachika HIV And AIDS: Another Deterrent To ‘Lobola’? Page 132 - 2 - Tinyade Kachika Lobola In Southern Africa: Its Implications On Women’s Page 136 Reproductive Rights Dr. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

PRACTICING AND TEACHING ARCHAEOLOGY IN EAST AFRICA: TANZANIA AND UGANDA By ASMERET GHEBREIGZIABIHER MEHARI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 © 2015 Asmeret Ghebreigziabiher Mehari To the people of Tanzania and Uganda, and in memory of my late sister Rozina Mogos and my friend Esther Nakaweesa ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been extremely blessed with generosities and inspirations from great people and institutions to reach this point. This dissertation is possible because of their guidance, generosities, and inspirations. I am grateful for the untiring collaborative guidance I have received from my chair Prof. Peter Schmidt and Co-chair Prof. Faye Harrison. I also extend my gratitude to my dissertation committee, Dr. Steven Brandt and Dr. Abraham Goldman. I would like to thank the mentors who laid the foundation for my academic interests at the University of Asmara, in Eritrea, because without their effort I would not have been able to pursue graduate school. In the Department of History, my gratitude goes to Drs. Uoldelul Chelati Dirar, John Distefano, and Richard Reid. In the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, I extend my gratitude to Dr. Abebe Kifleyesus, the late Dr. Alexander Naty, and Dr. Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad. In the Department of Archaeology, I am hugely indebted to Dr. Mathew Curtis, Dr. Alvaro Higueras, and Prof. Peter Schmidt for sharing their passion of archaeology. I am also indebted to Dr. Yosief Libsekal and Mr. Rezene Russom for paving the road for me and many other Eritrean students of archaeology.