Title MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: a CASE STUDY of LANGUAGE USE in the WEST UGANDAN TOWN of HOIMA Author(S) KAJI, Shigeki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

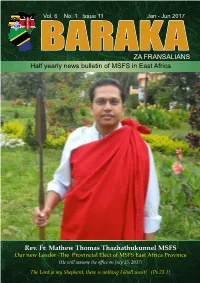

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

Becoming Christian: Personhood and Moral Cosmology in Acholi South

Becoming Christian: Personhood and Moral Cosmology in Acholi South Sudan Ryan Joseph O’Byrne Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL) September, 2016 1 DECLARATION I, Ryan Joseph O’Byrne, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where material has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Ryan Joseph O’Byrne, 21 September 2016 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines contemporary entanglements between two cosmo-ontological systems within one African community. The first system is the indigenous cosmology of the Acholi community of Pajok, South Sudan; the other is the world religion of evangelical Protestantism. Christianity has been in the region around 100 years, and although the current religious field represents a significant shift from earlier compositions, the continuing effects of colonial and early missionary encounters have had significant impact. This thesis seeks to understand the cosmological transformations involved in all these encounters. This thesis provides the first in-depth account of South Sudanese Acholi – a group almost entirely absent from the ethnographic record. However, its largest contributions come through wider theoretical and ethnographic insights gained in attending to local Acholi cosmological, ontological, and experiential orientations. These contributions are: firstly, the connection of Melanesian ideas of agency and personhood to Africa, demonstrating not only the relational nature of Acholi personhood but an understanding of agency acknowledging nonhuman actors; secondly, a demonstration of the primarily relational nature of local personhood whereby Acholi and evangelical persons and relations are similarly structured; and thirdly, an argument that, in South Sudan, both systems are ultimately about how people organise the moral fabric of their society. -

Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak Minihydro

FILE Coey 5 Public Disclosure Authorized Report /02 Environmental Public Disclosure Authorized Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro (Revised v.2) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ECON-Report no. /02, Project no. 36200 <Velg tilgjengelighet> ISSN: 0803-5113, ISBN 82-7645-xxx-x e/,, 9. January 2003 Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro Commissioned by West Nile Concession Committee Prepared by EMA & ECON ECON Centre for Economic Analysis P.O.Box 6823 St. Olavs plass, 0130 Oslo, Norway. Phone: + 47 22 98 98 50, Fax: + 47 22 11 00 80, http://www.econ.no - EMA & ECON - Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro 4.3 Geologic Conditions .............. 26 4.4 Project Optimisation .............. 26 4.5 Diversion Weir and Fore bay .............. 27 4.6 Regulating Basin and Penstock .............. 28 4.7 Powerhouse .............. 28 5 EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE . ............................30 5.1 Physical Environment .............................. 30 5.1.1 Climate and Weather Patterns .............................. 30 5.1.2 Geomorphology, geology and soils .............................. 30 5.1.3 Hydrology .............................. 32 5.1.4 Seismology .............................. 32 5.2 Vegetation .............................. 33 5.3 Wildlife .............................. 34 5.3.1 Mammals .............................. 34 5.3.2 Birds .............................. 34 5.3.3 Fisheries .............................. 34 5.3.4 Reptiles .............................. 35 5.4 Socio-economics -

8 AFRICA 8 Ask God to Use the Truth Found in His Word to Mature Those Who Follow Christ

8 AFRICA 8 Ask God to use the truth found in His Word to mature those who follow Christ. May the Scriptures draw CIDA; AFRICA others into a transforming relationship with Him. Praise the Lord! A production of dramatized MARBLE; AFRICA Scripture stories in Cida is now complete and the stories are being released one at a time on the Internet. The main translator in the Marble New Testament The Scripture website is getting about one thousand project suffered from ongoing health problems that hits a week, mostly from speakers of the language who prevented her from working. Praise the Lord that have immigrated to other countries. Pray that the she is now able to work again. Ask God to continue translation team will find ways to get the recordings to heal her body and keep her from further relapses. directly into the country, possibly through radio Pray for final revisions and consultant checks on broadcasts. Ask God to give creativity to the team as the manuscript to be completed so that the New they consider how to improve the online feedback Testament can be recorded and distributed in audio mechanism in order to increase communications format; it will then also be printed. Ask the Lord to between the audience and a local believer who is direct the team in finding the best ways to distribute responding to their questions and comments. Above these Scriptures, and for hearts eager to receive them. all, pray that these products will result in new NARA; AFRICA believers and communities of faith. Rejoice! The Nara New Testament is now available in KWEME; AFRICA (40,000) audio and PDF format on the Internet! Local believers The Kweme New Testament was completed and are increasingly interested in the translation as they an additional review of it was carried out last year. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

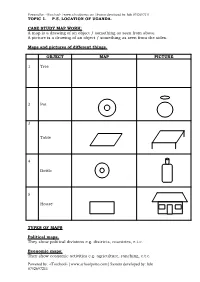

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Surrogate Surfaces: a Contextual Interpretive Approach to the Rock Art of Uganda

SURROGATE SURFACES: A CONTEXTUAL INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO THE ROCK ART OF UGANDA by Catherine Namono The Rock Art Research Institute Department of Archaeology School of Geography, Archaeology & Environmental Studies University of the Witwatersrand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 i ii Declaration I declare that this is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. Signed:……………………………….. Catherine Namono 5th March 2010 iii Dedication To the memory of my beloved mother, Joyce Lucy Epaku Wambwa To my beloved father and friend, Engineer Martin Wangutusi Wambwa To my twin, Phillip Mukhwana Wambwa and Dear sisters and brothers, nieces and nephews iv Acknowledgements There are so many things to be thankful for and so many people to give gratitude to that I will not forget them, but only mention a few. First and foremost, I am grateful to my mentor and supervisor, Associate Professor Benjamin Smith who has had an immense impact on my academic evolution, for guidance on previous drafts and for the insightful discussions that helped direct this study. Smith‘s previous intellectual contribution has been one of the corner stones around which this thesis was built. I extend deep gratitude to Professor David Lewis-Williams for his constant encouragement, the many discussions and comments on parts of this study. His invaluable contribution helped ideas to ferment. -

Towards a Spirituality of Reconciliation with Special Reference to the Lendu and Hema People in the Diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo) Alfred Ndrabu Buju

Towards a spirituality of reconciliation with special reference to the Lendu and Hema people in the diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo) Alfred Ndrabu Buju To cite this version: Alfred Ndrabu Buju. Towards a spirituality of reconciliation with special reference to the Lendu and Hema people in the diocese of Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo). Religions. 2002. dumas- 01295025 HAL Id: dumas-01295025 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01295025 Submitted on 30 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN AFRICA FACULTY OF THEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SPIRITUAL THEOLOGY TOWARDS A SI'IRITUALITY OF RECONCILIATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE LENDU AND IIEMA PEOPLE IN THE DIOCESE OF BUNIA / DRC IFRA 111111111111 111111111111111111 I F RA001643 o o 3 j)'VA Lr .2 8 A Thesis Sulimitted to the Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Licentiate Degree in Spiritual Theology By Rev. Fr. Ndrabu 13itju Alfred May 2002 tt. it Y 1 , JJ Nairobi-ken;• _ .../i"; .1 tic? ‘vii-.11:3! ..y/ror/tro DECLARATION THE CATIIOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN AFRICA Thesis Title: TOWARDS A SPIRITUALITY OF RECONCILIATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LENDU AND IIEMA PEOPLE IN TIIE DIOCESE OF BUNIA/DRC By Rev. -

African Mythology a to Z

African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z Celtic Mythology A to Z Chinese Mythology A to Z Egyptian Mythology A to Z Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z Japanese Mythology A to Z Native American Mythology A to Z Norse Mythology A to Z South and Meso-American Mythology A to Z MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION 8 Patricia Ann Lynch Revised by Jeremy Roberts [ African Mythology A to Z, Second Edition Copyright © 2004, 2010 by Patricia Ann Lynch All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Chelsea House 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lynch, Patricia Ann. African mythology A to Z / Patricia Ann Lynch ; revised by Jeremy Roberts. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60413-415-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Mythology—African. 2. Encyclopedias—juvenile. I. Roberts, Jeremy, 1956- II. Title. BL2400 .L96 2010 299.6' 11303—dc22 2009033612 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web at http://www.chelseahouse.com Text design by Lina Farinella Map design by Patricia Meschino Composition by Mary Susan Ryan-Flynn Cover printed by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Bood printed and bound by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Date printed: March 2010 Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda

Sub–Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program The World Bank and Economic Commission for Africa SSATP Working Paper No 12 Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda Christina Malmberg Calvo February 1994 Environmentally Sustainable Development Division Africa Region The World Bank Foreword One of the objectives of the Rural Travel and Transport Project (RTTP) is to recommend approaches for improving rural transport, including the adoption of intermediate transport technologies to facilitate goods movement and increase personal mobility. For this purpose, comprehensive village-level travel and transport surveys (VLTTS) and associated case studies have been carried out. The case studies focus on the role of intermediate means of transport (IMT) in improving mobility and the role of transport in women's daily lives. The present divisional working paper is the second in a series reporting on the VLTTS. The first working paper focussed on travel to meet domestic needs (for water, firewood, and food processing needs), and on the impact on women of the provision of such facilities as water supply, woodlots, fuel efficient stoves and grinding mills. The present case study documents the use of bicycles in eastern Uganda where they are a means of generating income for rural traders and for urban poor who work as bicycle taxi-riders. It also assesses women's priorities regarding interventions to improve mobility and access, and the potential for greater use of bicycles by rural women and for women's activities. The bicycle is the most common IMT in SSA, and it is used to improve the efficiency of productive tasks, and to serve as a link between farms and villages, nearby road networks, and market towns. -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10.