Tribes” to “Regions”;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen

Remota Relata Srudia Orientalia 97, Helsinki 20O3,pp.65-76 Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen This article gives a short outline of the early, sometimes controversial, records of Bantu peoples and languages. While the term Bantu has been in use since the mid lgth century, the earliest attempts at describing a Bantu language were made in the lTth century. However, extensive description of the individual Bantu languages started only in the l9th century @oke l96lab; Doke 1967; Wolff 1981: 2l). Scholars have made great efforts in trying to trace the earliest record of the peoples currently known as Bantu. What is considered as proven with considerable certainty is that the first person who brought the term Bantu to the knowledge of scholars of Africa was W. H. L Bleek. When precisely this happened is not fully clear. The year given is sometimes 1856, when he published The lnnguages of Mosambique, oÍ 1869, which is the year of publication of his unfinished, yet great work A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages.In The Languages of Mosambiqu¿ he writes: <<The languages of these vocabularies all belong to that great family which, with the exception of the Hottentot dialects, includes the whole of South Africa, and most of the tongues of Western Africa>. However, in this context he does not mention the name of the language family concemed. Silverstein (1968) pointed out that the first year when the word Bantu is found written by Bleek is 1857. That year Bleek prepared a manuscript Zulu Legends (printed as late as 1952), in which he stated: <<The word 'aBa-ntu' (men, people) means 'Par excellence' individuals of the Kafir race, particularly in opposition to the noun 'aBe-lungu' (white men). -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

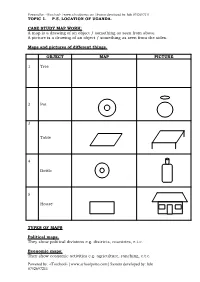

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Odoki, B. Challenges of Constitution-Making in Uganda

264 ConstiiuIioaalis,,i ii, Africa 15 challenge in courts of law. The controversialprovisionsmainlyrelate to the politicalsystemespecially the issue ofsuspension ofpoliticalpartyactivities, TheChallenges ofConstitution-makingand thereferendum on politicalsystems, the entrenchmentofthemovementsystem in the constitution,federalism, and the issue of land. in Implementation Uganda The implementation of the constitutionposesperhapsmore difficult challengesthan its making.There is a need to make theconstitution a dynamic Benjamin J. Odoki instrument, and a livinginstitution, in the minds and hearts of all Ugandans. Theconstitutionmust be iiiternalised and understood in order for the people to trulyrespect,observe and uphold it. It must be implemented in both the and to the letter.There is a need to establish and nurturedemocratic Themaking of a newconstitution in Ugandamarked an importantwatershed in spirit the history of the country. It demonstrated the desire of the people to institutions to promotedemocraticvalues andpracticeswithin the country. It is then that a culture of constitutionalism can be the fundamentallychange their system of governance into a truly democratic only promotedamongst and theirleaders. one. The process gave the people an opportunity to make a fresh start by people This examines the and that reviewingtheirpastexperiences,identifying the rootcauses oftheirproblems, chapter challenges problems wereexperienced the actors in the theNRM learninglessonsfrompastmistakesandmaking a concertedeffort to provide by major constitution-makingprocess: -

Genomic Evidence for Shared Common Ancestry of East African Hunting-Gathering Populations and Insights Into Local Adaptation

Genomic evidence for shared common ancestry of East African hunting-gathering populations and insights into local adaptation Laura B. Scheinfeldta,1,2, Sameer Soia,b,1, Charla Lamberta,3, Wen-Ya Koa,4, Aoua Coulibalya, Alessia Ranciaroa, Simon Thompsona, Jibril Hirboa,5, William Beggsa, Muntaser Ibrahimc, Thomas Nyambod, Sabah Omare, Dawit Woldemeskelf, Gurja Belayf, Alain Fromentg, Junhyong Kimh, and Sarah A. Tishkoffa,h,6 aDepartment of Genetics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; bGenomics and Computational Biology Graduate Program, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; cDepartment of Molecular Biology, Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan; dDepartment of Biochemistry, St. Joseph University College of Health Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; eKenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Biotechnology Research and Development, Nairobi, Kenya; fDepartment of Biology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; gUMR 208, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement-Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Musée de l’Homme, 75116 Paris, France; and hDepartment of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Contributed by Sarah A. Tishkoff, January 5, 2019 (sent for review October 15, 2018; reviewed by Rob J. Kulathinal and Mark D. Shriver) Anatomically modern humans arose in Africa ∼300,000 years ago, lithic ∼5 kya (7). This expansion, commonly referred to as the but the demographic and adaptive histories of African populations “Bantu expansion,” significantly impacted the landscape of ge- are not well-characterized. Here, we have generated a genome- netic and cultural diversity in Africa (8, 9). While Bantu lan- wide dataset from 840 Africans, residing in western, eastern, guages, which belong to the Niger-Congo (NC) language family, southern, and northern Africa, belonging to 50 ethnicities, and are widely spoken across Africa, languages belonging to two speaking languages belonging to four language families. -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

Wildlife and Spiritual Knowledge at the Edge of Protected Areas: Raising Another Voice in Conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2018, 7:12 (07 September 2018) doi:10.15451/ec2018-08-7.12-1-26 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Wildlife and spiritual knowledge at the edge of protected areas: raising another voice in conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A. Chapman5; Wilson Kagoro6; Andrew Seguya6; Marianne Cohen7 ABSTRACT International guidelines recommend the integration of local communities within protected areas management as a means to improve conservation efforts. However, local management plans rarely consider communities knowledge about wildlife and their traditions to promote biodiversity conservation. In the Sebitoli area of Kibale National Park, Uganda, the contact of local communities with wildlife has been strictly limited at least since the establishment of the park in 1993. The park has not develop programs, outside of touristic sites, to promote local traditions, knowledge, and beliefs in order to link neighboring community members to nature. To investigate such links, we used a combination of semidirected interviews and participative observations (N= 31) with three communities. While human and wildlife territories are legally disjointed, results show that traditional wildlife and spiritual related knowledge trespasses them and the contact with nature is maintained though practice, culture, and imagination. More than 66% of the people we interviewed have wild animals as totems, and continue to use plants to medicate, cook, or build. Five spirits structure humanwildlife relationships at specific sacred sites. However, this knowledge varies as a function of the location of local communities and the sacred sites. A better integration of local wildlifefriendly knowledge into management plans may revive communities’ connectedness to nature, motivate conservation behaviors, and promote biodiversity conservation. -

Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Current Issues Background Contacts Resources

Angola - Minority Rights Group https://minorityrights.org/country/angola/ Minorities and indigenous peoples Current issues Background Contacts Resources Main languages: according to the 2014 Census, while the majority (71 per cent) of Angolans speak Portuguese – the only official language – at home, other languages spoken include Umbundu (23 per cent), Kikongo (8 per cent), Kimbundu (8 per cent), Chokwe (7 per cent), Nhaneca (3 per cent), Nganguela (3 per cent), Fiote (2 per cent), Kwanhama (2 per cent), Muhumbi (2 per cent), Luvale (1 per cent), others (4 per cent) Main religions: indigenous beliefs, Christianity Angola’s 2014 Census, the first since 1970, included information on language most used in the home, but not on ethnicity. Other sources indicate that Angola’s ethnic groups include Ovimbundu (37 per cent), Mbundu (25 per cent), Bakongo (13 per cent) and mestiço (2 per cent), Lunda-Chokwe (8 per cent), Nyaneka-Nkumbi (3 per cent), Ambo (2 per cent), Herero (up to 0.5 per cent), San 3,600 and Kwisi (up to 0.5 per cent). However, the international indigenous peoples’ rights organization IWGIA puts the number of indigenous people including San, Himba, Kwepe, Kuvale and Zwemba at around 25,000, amounting to 0.1 per cent of the total population, with San alone numbering between 5,000 and 14,000. The majority of today’s Angolans are Bantu peoples, including Ovimbundu, Mbundu and Bakongo, while the San belong to the indigenous Khoisan people. Traditionally a largely rural people of the central highlands, Ovimbundu migrated to the cities in large numbers in search of employment in the twentieth century. -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, In: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54

Africa Spectrum Quinn, Joanna R. (2014), Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, in: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-7811 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2014: 29-54 Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda Joanna R. Quinn Abstract: This contribution traces the importance of traditional institu- tions in rehabilitating societies in general terms and more particularly in post-independence Uganda. The current regime, partly by inventing “traditional” cultural institutions, partly by co-opting them for its own interests, contributed to a loss of legitimacy of those who claim respon- sibility for customary law. More recently, international prosecutions have complicated the use of customary mechanisms within such societies. -

Monolingualism Via Multilingualism: a Case Study of Language Use in the West Ugandan Town of Hoima

African Study Monographs, 34 (1): 1–25, March 2013 1 MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: A CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE USE IN THE WEST UGANDAN TOWN OF HOIMA Shigeki KAJI Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Multilingualism is one of the most salient features of language use in Africa and, at first sight, Uganda appears to be just one example of this practice. However, as Uganda has no lingua franca that is widely used by its entire population, questions about how people cope with multilingualism arise. Answers to such questions can be found in the fact that people are able to create a monolingual state in a given area because everyone is multilingual. That is, people speak their own language in their own domain and speak other peoples’ languages when they go to the latter’s domains. This conclusion emerged from interviews conducted with 100 inhabitants of Hoima city in western Uganda, an area primarily inhabited by the Nyoro people. The linguistic situation in Hoima provides a valuable case study of what can happen in the absence of a fully developed lingua franca and can contribute to broader discussions of language use in Africa. Key Words: Lingua franca; Multilingualism; Hoima; Nyoro; Uganda. INTRODUCTION I have conducted linguistic research in Uganda since 2001. The main themes of my research relate to the grammatical and lexical characteristics of little-known languages in the area. In the course of research, however, I noticed differences between the use of language in Uganda and that in the regions where I had studied before. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

The Bantu Peoples (C.1200B.C.–C. 500 A.D.)

The Bantu peoples (c.1200B.C.–c. 500 A.D.) Source: "Africa." Ancient Civilizations Reference Library. Ed. Judson Knight and Stacy A. McConnell. Detroit: UXL, 2000. Student Resources in Context. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. Document URL http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/suic/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?query=&prodId=SUIC&contentModules=&displayGroupName=Reference&limiter=& disableHighlighting=false&displayGroups=&sortBy=&search_within_results=&p=SUIC&action=2&catId=&activityType=&documentId=GALE%7CEJ2173150025&source =Bookmark&u=cobb90289&jsid=12014b7b7403f7ce1fe03dbbe6faade6 Around the area of modern-day Nigeria, the Bantu (BAHN-too) peoples had their origins. In some regards, the Bantu do not qualify as a full-fledged civilization. They had no written language, nor did they build cities or even stay in one spot. Theirs was a history characterized by migration, as they moved out of their homeland in about 1200 B.C. to spread throughout southern Africa. In fact, the Bantu were not even a nation or a unified group of people in the way that the Egyptians, Kushites, or Aksumites were. They were simply a group of more or less related peoples, all sub-Saharan African (i.e., "black") in origin. However, as in many other instances, the important distinction is one of language, not race. It was language that gave the Bantu peoples their distinctive character, which has influenced the culture of southern Africa up to the present day. Though they spoke a variety of tongues, they all used the same word for "people": bantu. Whether or not they qualified as a true civilization, the Bantu had a strongly developed culture based on family ties. Families became grouped into clans, and clans into tribes.