Drc Survey: an Overview of Demographics, Health, and Financial Services in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

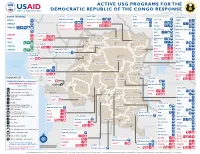

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Download File

UNICEF DRC | COVID-19 Situation Report COVID-19 Situation Report #9 29 May-10 June 2020 /Desjardins COVID-19 overview Highlights (as of 10 June 2020) 25702 • 4.4 million children have access to distance learning UNI3 confirmed thanks to partnerships with 268 radio stations and 20 TV 4,480 cases channels © UNICEF/ UNICEF’s response deaths • More than 19 million people reached with key messages 96 on how to prevent COVID-19 people 565 recovered • 29,870 calls managed by the COVID-19 Hotline • 4,338 people (including 811 children) affected by COVID-19 cases under 388 investigation and 837 frontline workers provided with psychosocial support • More than 200,000 community masks distributed 2.3% Fatality Rate 392 new samples tested UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response Kinshasa recorded 88.8% (3,980) of all confirmed cases. Other affected provinces including # of cases are: # of people reached on COVID-19 through North Kivu (35) South Kivu (89) messaging on prevention and access to 48% Ituri (2) Kongo Central (221) Haut RCCE* services Katanga (38) Kwilu (2) Kwango (1) # of people reached with critical WASH Haut Lomami (1) Tshopo (1) supplies (including hygiene items) and services 78% IPC** Equateur (1) # of children who are victims of violence, including GBV, abuse, neglect or living outside 88% DRC COVID-19 Response PSS*** of a family setting that are identified and… Funding Status # of children and women receiving essential healthcare services in UNICEF supported 34% Health facilities Funds # of caregivers of children (0-23 months) available* DRC COVID-19 reached with messages on breadstfeeding in 15% 30% Funding the context of COVID-19 requirements* : Nutrition $ 58,036,209 # of children supported with distance/home- 29% based learning Funding Education Gap 70% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Funds available include 9 million USD * Risk Communication and Community Engagement UNICEF regular ressources allocated by ** Infection Prevention and Control the office for first response needs. -

Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen

Remota Relata Srudia Orientalia 97, Helsinki 20O3,pp.65-76 Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen This article gives a short outline of the early, sometimes controversial, records of Bantu peoples and languages. While the term Bantu has been in use since the mid lgth century, the earliest attempts at describing a Bantu language were made in the lTth century. However, extensive description of the individual Bantu languages started only in the l9th century @oke l96lab; Doke 1967; Wolff 1981: 2l). Scholars have made great efforts in trying to trace the earliest record of the peoples currently known as Bantu. What is considered as proven with considerable certainty is that the first person who brought the term Bantu to the knowledge of scholars of Africa was W. H. L Bleek. When precisely this happened is not fully clear. The year given is sometimes 1856, when he published The lnnguages of Mosambique, oÍ 1869, which is the year of publication of his unfinished, yet great work A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages.In The Languages of Mosambiqu¿ he writes: <<The languages of these vocabularies all belong to that great family which, with the exception of the Hottentot dialects, includes the whole of South Africa, and most of the tongues of Western Africa>. However, in this context he does not mention the name of the language family concemed. Silverstein (1968) pointed out that the first year when the word Bantu is found written by Bleek is 1857. That year Bleek prepared a manuscript Zulu Legends (printed as late as 1952), in which he stated: <<The word 'aBa-ntu' (men, people) means 'Par excellence' individuals of the Kafir race, particularly in opposition to the noun 'aBe-lungu' (white men). -

A Turning Point for Manual Drilling in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Rural Water Supply Network Publication 2020-2 C H Kane & Dr K Danert 2020 A Turning Point for Manual Drilling in the Democratic Republic of Congo Publication 2020-2 Dedication Summary The authors dedicate this publication to Gambo Nayou This publication provides a source of inspiration from a country that (1963 to 2016). tends to otherwise be associated with humanitarian crisis, persistent con- flicts, recurrent civil wars and a generally obsolete road infrastructure. It describes over a decade of pioneering efforts by UNICEF, the Gov- ernment of the Democratic Republic of Congo and partners to intro- duce and professionalise manual drilling. This professionalisation pro- gramme is very important as it is estimated that only 43% of the pop- ulation have access to a basic drinking water service (JMP, 2019). In addition, the majority of the DRC is favourable to manual drilling (42% classified with very high or high potential, and 24% as moderate). The most favourable area for manual drilling is in the western part of Gambo was a man of vision, a person who looked into the future and the country, which has a soft geological layer of considerable extent saw things that many could not even imagine. He passionately and thickness. shared what he knew with others. Over a ten-year period, manual drilling, using the rota-jetting tech- Following his experiences of manual drilling in Niger and Chad, nique, has gone from a little-known technology in the DRC to an ef- Gambo reached out to the Association of Manual Drillers from Chad fective technology that has enabled about 650,000 people to be pro- (Tchadienne pour la Promotion des Entreprises Spécialisées en For- vided with a water service. -

World Bank Document

.. HOLD FOR RELEASE • INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 1818 H STREET. ·N.W, WASHINGTON 25, D. C TE' EPHONE. EXECUTIVE 3-6360 Public Disclosure Authorized I:JA Press Release No. 69/19 Subject: IDA and UNDP financing for May 7, 1969 highway technical assistance in Congo (Kinshasa.) A credit of $6 million from the International Development Association (IDA) and a $1.5 million technical assistance grant from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) will enable th~ Government to take the first steps toward rehabilitating its highway network. Public Disclosure Authorized The Government is contributing the equivalent of $2 million toward the cost of the project. The Congo's major centers of population, production and trade are widely s~nttered and an efficient and extensive transport system is essential if the • c,.·,untry is to be integrated administratively, politically and economically. Tile once efficient rail, river and road transport system has deteriorated since 1.udependence and the difficulties which followed. The condition of the highways Public Disclosure Authorized is particularly acute because of a serious weakening of administration, and lack of maintenance and of equipment replacements. The measures now to be undertaken are of an emergency nature and only a small part of what has to be done to establish a viable highway system and administration. However, they will assure more efficient use of personnel and ·funds being used for highway maintenance and rehabilitation; halt the r~1r:i.d deterioration of some of the most important roads; achieve substantial Public Disclosure Authorized s;.:v-tngs in vehicle operating costs; and will encourage incn:?ased production ~-7 ?emoving potential bottlenecks to economic recovery • • /more \ IDA P.R. -

Odoki, B. Challenges of Constitution-Making in Uganda

264 ConstiiuIioaalis,,i ii, Africa 15 challenge in courts of law. The controversialprovisionsmainlyrelate to the politicalsystemespecially the issue ofsuspension ofpoliticalpartyactivities, TheChallenges ofConstitution-makingand thereferendum on politicalsystems, the entrenchmentofthemovementsystem in the constitution,federalism, and the issue of land. in Implementation Uganda The implementation of the constitutionposesperhapsmore difficult challengesthan its making.There is a need to make theconstitution a dynamic Benjamin J. Odoki instrument, and a livinginstitution, in the minds and hearts of all Ugandans. Theconstitutionmust be iiiternalised and understood in order for the people to trulyrespect,observe and uphold it. It must be implemented in both the and to the letter.There is a need to establish and nurturedemocratic Themaking of a newconstitution in Ugandamarked an importantwatershed in spirit the history of the country. It demonstrated the desire of the people to institutions to promotedemocraticvalues andpracticeswithin the country. It is then that a culture of constitutionalism can be the fundamentallychange their system of governance into a truly democratic only promotedamongst and theirleaders. one. The process gave the people an opportunity to make a fresh start by people This examines the and that reviewingtheirpastexperiences,identifying the rootcauses oftheirproblems, chapter challenges problems wereexperienced the actors in the theNRM learninglessonsfrompastmistakesandmaking a concertedeffort to provide by major constitution-makingprocess: -

Genomic Evidence for Shared Common Ancestry of East African Hunting-Gathering Populations and Insights Into Local Adaptation

Genomic evidence for shared common ancestry of East African hunting-gathering populations and insights into local adaptation Laura B. Scheinfeldta,1,2, Sameer Soia,b,1, Charla Lamberta,3, Wen-Ya Koa,4, Aoua Coulibalya, Alessia Ranciaroa, Simon Thompsona, Jibril Hirboa,5, William Beggsa, Muntaser Ibrahimc, Thomas Nyambod, Sabah Omare, Dawit Woldemeskelf, Gurja Belayf, Alain Fromentg, Junhyong Kimh, and Sarah A. Tishkoffa,h,6 aDepartment of Genetics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; bGenomics and Computational Biology Graduate Program, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; cDepartment of Molecular Biology, Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan; dDepartment of Biochemistry, St. Joseph University College of Health Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; eKenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Biotechnology Research and Development, Nairobi, Kenya; fDepartment of Biology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; gUMR 208, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement-Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Musée de l’Homme, 75116 Paris, France; and hDepartment of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Contributed by Sarah A. Tishkoff, January 5, 2019 (sent for review October 15, 2018; reviewed by Rob J. Kulathinal and Mark D. Shriver) Anatomically modern humans arose in Africa ∼300,000 years ago, lithic ∼5 kya (7). This expansion, commonly referred to as the but the demographic and adaptive histories of African populations “Bantu expansion,” significantly impacted the landscape of ge- are not well-characterized. Here, we have generated a genome- netic and cultural diversity in Africa (8, 9). While Bantu lan- wide dataset from 840 Africans, residing in western, eastern, guages, which belong to the Niger-Congo (NC) language family, southern, and northern Africa, belonging to 50 ethnicities, and are widely spoken across Africa, languages belonging to two speaking languages belonging to four language families. -

Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Thomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 The effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Current Issues Background Contacts Resources

Angola - Minority Rights Group https://minorityrights.org/country/angola/ Minorities and indigenous peoples Current issues Background Contacts Resources Main languages: according to the 2014 Census, while the majority (71 per cent) of Angolans speak Portuguese – the only official language – at home, other languages spoken include Umbundu (23 per cent), Kikongo (8 per cent), Kimbundu (8 per cent), Chokwe (7 per cent), Nhaneca (3 per cent), Nganguela (3 per cent), Fiote (2 per cent), Kwanhama (2 per cent), Muhumbi (2 per cent), Luvale (1 per cent), others (4 per cent) Main religions: indigenous beliefs, Christianity Angola’s 2014 Census, the first since 1970, included information on language most used in the home, but not on ethnicity. Other sources indicate that Angola’s ethnic groups include Ovimbundu (37 per cent), Mbundu (25 per cent), Bakongo (13 per cent) and mestiço (2 per cent), Lunda-Chokwe (8 per cent), Nyaneka-Nkumbi (3 per cent), Ambo (2 per cent), Herero (up to 0.5 per cent), San 3,600 and Kwisi (up to 0.5 per cent). However, the international indigenous peoples’ rights organization IWGIA puts the number of indigenous people including San, Himba, Kwepe, Kuvale and Zwemba at around 25,000, amounting to 0.1 per cent of the total population, with San alone numbering between 5,000 and 14,000. The majority of today’s Angolans are Bantu peoples, including Ovimbundu, Mbundu and Bakongo, while the San belong to the indigenous Khoisan people. Traditionally a largely rural people of the central highlands, Ovimbundu migrated to the cities in large numbers in search of employment in the twentieth century. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

The Bantu Peoples (C.1200B.C.–C. 500 A.D.)

The Bantu peoples (c.1200B.C.–c. 500 A.D.) Source: "Africa." Ancient Civilizations Reference Library. Ed. Judson Knight and Stacy A. McConnell. Detroit: UXL, 2000. Student Resources in Context. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. Document URL http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/suic/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?query=&prodId=SUIC&contentModules=&displayGroupName=Reference&limiter=& disableHighlighting=false&displayGroups=&sortBy=&search_within_results=&p=SUIC&action=2&catId=&activityType=&documentId=GALE%7CEJ2173150025&source =Bookmark&u=cobb90289&jsid=12014b7b7403f7ce1fe03dbbe6faade6 Around the area of modern-day Nigeria, the Bantu (BAHN-too) peoples had their origins. In some regards, the Bantu do not qualify as a full-fledged civilization. They had no written language, nor did they build cities or even stay in one spot. Theirs was a history characterized by migration, as they moved out of their homeland in about 1200 B.C. to spread throughout southern Africa. In fact, the Bantu were not even a nation or a unified group of people in the way that the Egyptians, Kushites, or Aksumites were. They were simply a group of more or less related peoples, all sub-Saharan African (i.e., "black") in origin. However, as in many other instances, the important distinction is one of language, not race. It was language that gave the Bantu peoples their distinctive character, which has influenced the culture of southern Africa up to the present day. Though they spoke a variety of tongues, they all used the same word for "people": bantu. Whether or not they qualified as a true civilization, the Bantu had a strongly developed culture based on family ties. Families became grouped into clans, and clans into tribes.