Communities in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of the Constitution. Preliminary matter. Arrangement of objectives. Arrangement of chapters and schedules. Arrangement of articles. Preamble. National objectives and directive principles of State policy. Chapters. Schedules. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy. Arrangement of Objectives. Objective General. I. Implementation of objectives. Political objectives. II. Democratic principles. III. National unity and stability. IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity. Protection and promotion of fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups. VII. Protection of the aged. VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of Government. IX. The right to development. X. Role of the people in development. XI. Role of the State in development. XII. Balanced and equitable development. XIII. Protection of natural resources. Social and economic objectives. XIV. General social and economic objectives. XV. Recognition of the role of women in society. XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities. XVII. Recreation and sports. XVIII. Educational objectives. XIX. Protection of the family. XX. Medical services. XXI. Clean and safe water. 1 XXII. Food security and nutrition. XXIII. Natural disasters. Cultural objectives. XXIV. Cultural objectives. XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage. Accountability. XXVI. Accountability. The environment. XXVII. The environment. Foreign policy objectives. XXVIII. Foreign policy objectives. Duties of a citizen. XXIX. Duties of a citizen. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of Chapters and Schedules. Chapter 1. The Constitution. 2. The Republic. -

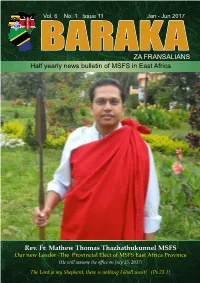

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION The 1991 Population and Housing Census Administrative Report that I now have the pleasure to submit, is the last publication among several reports that mark the completion of the 5th systematic Population Census held in Uganda since 1948 when the first fairly systematic census was carried out. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was the first census in the country to include a fairly detailed survey of the stock and conditions of housing in Uganda. The central concern of this report is to describe in some detail, the trials and tribulations of the administration and management of the 1991 Population and Housing Census. It reveals aspects of successes recorded and problems encountered in the course of managing the three stage activities of the census, namely the pre- enumeration, enumeration and post-enumeration activities. It is our hope that a detailed description of what took place through all these phases will guide future census administrators in this country and help the data users to determine the likely accuracy, of, and strengthen their faith in, the data they are using. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was a result of an agreement between the Government of Uganda and the UNFPA signed in March, 1989 although the idea and negotiations started way back in 1986. For various logistical reasons, the date of enumeration was shifted from August, 1990 to November/December the same year, and finally to January, 1991, which made it close to eleven years from the date of the 1980 census. The census project was funded by the Government of Uganda to the tune of U Shs 2.2 billion and by the UNFPA and UNDP at $5.7 million, DANIDA $ 850,000 and USAID shs. -

KIBAALE Q2 REPORT.Pdf

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 524 Kibaale District 2016/17 Quarter 2 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:524 Kibaale District for FY 2016/17. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Kibaale District Date: 2/23/2017 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 524 Kibaale District 2016/17 Quarter 2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % Receipts Budget UShs 000's Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 324,423 110,946 34% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,317,300 1,689,547 51% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 11,753,523 6,056,632 52% 2c. Other Government Transfers 462,787 183,207 40% 4. Donor Funding 933,368 113,575 12% Total Revenues 16,791,401 8,153,907 49% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved Budget Cumulative Cumulative % % % Releases Expenditure Budget -

Land Reform and Sustainable Livelihoods

! M4 -vJ / / / o rtr £,/- -n AO ^ l> /4- e^^/of^'i e i & ' cy6; s 6 cy6; S 6 s- ' c fwsrnun Of WVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY Acknowledgements The researchers would like to thank Ireland Aid and APSO for funding the research; the Ministers for Agriculture and Lands, Dr. Kisamba Mugerwa and Hon. Baguma Isoke for their support and contribution; and the Irish Embassy in Kampala for its support. Many thanks also to all who provided valuable insights into the research topic through interviews, focus group discussions and questionnaire surveys in Kampala and Kibaale District. Finally: a special word of thanks to supervisors and research fellows in MISR, particularly Mr Patrick Mulindwa who co-ordinated most of the field-based activities, and to Mr. Nick Chisholm in UCC for advice and direction particularly at design and analysis stages. BLDS (British Library for Development Studies) Institute of Development Studies Brighton BN1 9RE Tel: (01273) 915659 Email: [email protected] Website: www.blds.ids.ac.uk Please return by: Executive Summary Chapter One - Background and Introduction This report is one of the direct outputs of policy orientated research on land tenure / land reform conducted in specific areas of Uganda and South Africa. The main goal of the research is to document information and analysis on key issues relating to the land reform programme in Uganda. It is intended that that the following pages will provide those involved with the land reform process in Kibaale with information on: • how the land reform process is being carried out at a local level • who the various resource users are, how they are involved in the land reform, and how each is likely to benefit / loose • empirical evidence on gainers and losers (if any) from reform in other countries • the gender implications of tenure reform • how conflicts over resource rights are dealt with • essential supports to the reform process (e.g. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

The State of Uganda Population Report 2008

The Republic of Uganda THE STATE OF UGANDA POPULATION REPORT 2008 Theme: “The Role of Culture, Gender and Human Rights in Social Transformation and Sustainable Development” Funded by UNFPA Uganda i UGANDA:T KEY DEMOGRAPHIC, SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS 2007 SUMMARY OF INDICATORS 1. Total Population (million) 29.6 2. Total Male Population (million) 14.2 3. Total Female Population (million) 15.2 4. Total Urban Population (million) 3.9 5. Population Growth Rate (%) 3.2 6. Urban Population Growth Rate (%) 5.7 7. Maternal Mortality Ratio per 100,000 live births 435 8. Infant Mortality Rate per 1,000 live births 76 9. Under five Mortality Rate per 1,000 live births 137 10. Total Fertility Rate 6.7 11. Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (%) 24 12. Supervised Deliveries (%) 42 13. Full Immunization (%) 46 14. Unmet Need for Family Planning (%) 41 15. Stunted Children (%) 38 16. HIV Prevalence Rate (%) 6.4 17. Literacy Rate (%) 69 18. Life Expectancy (years) 50.4 19. Population in Poverty (%)) 31 20. Human Development Index 0.581 21. GDP per capita in 2007 (US $) 370 22. Real GDP Growth Rate 2007/08 (%) 8.9 23. Private investment Growth in 2007/08 (%) 15 24. Public investment Growth in 2007/08 (%) 23 ii TABLE OF CONTENT KeyTU Demographic, Social and Development Indicators 2007 UT ................................................... iiiT ListU of TablesU ........................................................................................................... iv ListU of FiguresU ......................................................................................................... -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Violence Against Women Policy and Practice in Uganda — Promoting Justice Within the Context of Patriarchy

Abstract Title of Dissertation: VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN POLICY AND PRACTICE IN UGANDA — PROMOTING JUSTICE WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF PATRIARCHY Diane Ruth Gardsbane, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Judith Noemi Freidenberg, Department of Anthropology The goal of this study was to understand how and whether policy and practice relating to violence against women in Uganda, especially Uganda’s Domestic Violence Act of 2010, have had an effect on women’s beliefs and practices, as well as on support and justice for women who experience abuse by their male partners. Research used multi-sited ethnography at transnational, national, and local levels to understand the context that affects what policies are developed, how they are implemented, and how, and whether, women benefit from these. Ethnography within a local community situated global and national dynamics within the lives of women. Women who experience VAW within their intimate partnerships in Uganda confront a political economy that undermines their access to justice, even as a women’s rights agenda is working to develop and implement laws, policies, and interventions that promote gender equality and women’s empowerment. This dissertation provides insights into the daily struggles of women who try to utilize policy that challenges duty bearers, in part because it is a new law, but also because it conflicts with the structural patriarchy that is engrained in Ugandan society. Two explanatory models were developed. One explains factors relating to a woman’s decision to seek support or to report domestic violence. The second explains why women do and do not report DV. Among the findings is that a woman is most likely to report abuse under the following circumstances: 1) her own, or her children’s survival (physical or economic) is severely threatened; 2) she experiences severe physical abuse; or, 3) she needs financial support for her children. -

Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda

Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda G. Shepherd and C. Kazoora with D. Mueller Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2013 The Forestry Policy and InstitutionsWorking Papers report on issues in the work programme of Fao. These working papers do not reflect any official position of FAO. Please refer to the FAO Web site (www.fao.org/forestry) for official information. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on ongoing activities and programmes, to facilitate dialogue and to stimulate discussion. The Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division works in the broad areas of strenghthening national institutional capacities, including research, education and extension; forest policies and governance; support to national forest programmes; forests, poverty alleviation and food security; participatory forestry and sustainable livelihoods. For further information, please contact: Fred Kafeero Forestry Officer Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division Forestry Department, FAO Viale Delle terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] Website: www.fao.org/forestry Comments and feedback are welcome. For quotation: FAO.2013. Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda, by, G. Shepherd, C. Kazoora and D. Mueller. Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper No. 32. Rome. Cover photo: Ankole Cattle of Uganda The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression af any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda

Sub–Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program The World Bank and Economic Commission for Africa SSATP Working Paper No 12 Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda Christina Malmberg Calvo February 1994 Environmentally Sustainable Development Division Africa Region The World Bank Foreword One of the objectives of the Rural Travel and Transport Project (RTTP) is to recommend approaches for improving rural transport, including the adoption of intermediate transport technologies to facilitate goods movement and increase personal mobility. For this purpose, comprehensive village-level travel and transport surveys (VLTTS) and associated case studies have been carried out. The case studies focus on the role of intermediate means of transport (IMT) in improving mobility and the role of transport in women's daily lives. The present divisional working paper is the second in a series reporting on the VLTTS. The first working paper focussed on travel to meet domestic needs (for water, firewood, and food processing needs), and on the impact on women of the provision of such facilities as water supply, woodlots, fuel efficient stoves and grinding mills. The present case study documents the use of bicycles in eastern Uganda where they are a means of generating income for rural traders and for urban poor who work as bicycle taxi-riders. It also assesses women's priorities regarding interventions to improve mobility and access, and the potential for greater use of bicycles by rural women and for women's activities. The bicycle is the most common IMT in SSA, and it is used to improve the efficiency of productive tasks, and to serve as a link between farms and villages, nearby road networks, and market towns.