Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of the Constitution. Preliminary matter. Arrangement of objectives. Arrangement of chapters and schedules. Arrangement of articles. Preamble. National objectives and directive principles of State policy. Chapters. Schedules. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy. Arrangement of Objectives. Objective General. I. Implementation of objectives. Political objectives. II. Democratic principles. III. National unity and stability. IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity. Protection and promotion of fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups. VII. Protection of the aged. VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of Government. IX. The right to development. X. Role of the people in development. XI. Role of the State in development. XII. Balanced and equitable development. XIII. Protection of natural resources. Social and economic objectives. XIV. General social and economic objectives. XV. Recognition of the role of women in society. XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities. XVII. Recreation and sports. XVIII. Educational objectives. XIX. Protection of the family. XX. Medical services. XXI. Clean and safe water. 1 XXII. Food security and nutrition. XXIII. Natural disasters. Cultural objectives. XXIV. Cultural objectives. XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage. Accountability. XXVI. Accountability. The environment. XXVII. The environment. Foreign policy objectives. XXVIII. Foreign policy objectives. Duties of a citizen. XXIX. Duties of a citizen. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of Chapters and Schedules. Chapter 1. The Constitution. 2. The Republic. -

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION The 1991 Population and Housing Census Administrative Report that I now have the pleasure to submit, is the last publication among several reports that mark the completion of the 5th systematic Population Census held in Uganda since 1948 when the first fairly systematic census was carried out. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was the first census in the country to include a fairly detailed survey of the stock and conditions of housing in Uganda. The central concern of this report is to describe in some detail, the trials and tribulations of the administration and management of the 1991 Population and Housing Census. It reveals aspects of successes recorded and problems encountered in the course of managing the three stage activities of the census, namely the pre- enumeration, enumeration and post-enumeration activities. It is our hope that a detailed description of what took place through all these phases will guide future census administrators in this country and help the data users to determine the likely accuracy, of, and strengthen their faith in, the data they are using. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was a result of an agreement between the Government of Uganda and the UNFPA signed in March, 1989 although the idea and negotiations started way back in 1986. For various logistical reasons, the date of enumeration was shifted from August, 1990 to November/December the same year, and finally to January, 1991, which made it close to eleven years from the date of the 1980 census. The census project was funded by the Government of Uganda to the tune of U Shs 2.2 billion and by the UNFPA and UNDP at $5.7 million, DANIDA $ 850,000 and USAID shs. -

Working Paper No. 141 PRE-COLONIAL POLITICAL

Working Paper No. 141 PRE-COLONIAL POLITICAL CENTRALIZATION AND CONTEMPORARY DEVELOPMENT IN UGANDA by Sanghamitra Bandyopadhyay and Elliott Green AFROBAROMETER WORKING PAPERS Working Paper No. 141 PRE-COLONIAL POLITICAL CENTRALIZATION AND CONTEMPORARY DEVELOPMENT IN UGANDA by Sanghamitra Bandyopadhyay and Elliott Green November 2012 Sanghamitra Bandyopadhyay is Lecturer in Economics, School of Business and Management, Queen Mary, University of London. Email: [email protected] Elliott Green is Lecturer in Development Studies, Department of International Development, London School of Economics. Email: [email protected] Copyright Afrobarometer i AFROBAROMETER WORKING PAPERS Editor Michael Bratton Editorial Board E. Gyimah-Boadi Carolyn Logan Robert Mattes Leonard Wantchekon Afrobarometer publications report the results of national sample surveys on the attitudes of citizens in selected African countries towards democracy, markets, civil society, and other aspects of development. The Afrobarometer is a collaborative enterprise of the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD, Ghana), the Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA), and the Institute for Empirical Research in Political Economy (IREEP) with support from Michigan State University (MSU) and the University of Cape Town, Center of Social Science Research (UCT/CSSR). Afrobarometer papers are simultaneously co-published by these partner institutions and the Globalbarometer. Working Papers and Briefings Papers can be downloaded in Adobe Acrobat format from www.afrobarometer.org. Idasa co-published with: Copyright Afrobarometer ii ABSTRACT The effects of pre-colonial history on contemporary African development have become an important field of study within development economics in recent years. In particular (Gennaioli & Rainer, 2007) suggest that pre-colonial political centralization has had a positive impact on contemporary levels of development within Africa at the country level. -

Papers of Beatrice Mary Blackwood (1889–1975) Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

PAPERS OF BEATRICE MARY BLACKWOOD (1889–1975) PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Compiled by B. Asbury and M. Peckett, 2013-15 Box 1 Correspondence A-D Envelope A (Box 1) 1. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 May 1955. Summary: Acknowledging receipt of the Pitt Rivers Report for 1954. “The Museum as an institution seems beset with more difficulties than any other.” Giving details of the developing organisation of the Vancouver Museum and its index card system. Asking for a copy of Mr Bradford’s BBC talk on the “Lost Continent of Atlantis”. Notification that Mr Menzies’ health has meant he cannot return to work at the Museum. 2pp. 2. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 July 1955. Summary: Thanks for the “Lost Continent of Atlantis” information. The two Museums have similar indexing problems. Excavations have been resumed at the Great Fraser Midden at Marpole under Dr Borden, who has dated the site to 50 AD using Carbon-14 samples. 2pp. 3. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 12 June 1957. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Mr Menzies and his health. The Vancouver Museum is expanding into enlarged premises. “Until now, the City Museum has truly been a cultural orphan.” 1pp. 4. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 16 June 1959. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Vancouver Museum developments. -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

The State of Uganda Population Report 2008

The Republic of Uganda THE STATE OF UGANDA POPULATION REPORT 2008 Theme: “The Role of Culture, Gender and Human Rights in Social Transformation and Sustainable Development” Funded by UNFPA Uganda i UGANDA:T KEY DEMOGRAPHIC, SOCIAL AND DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS 2007 SUMMARY OF INDICATORS 1. Total Population (million) 29.6 2. Total Male Population (million) 14.2 3. Total Female Population (million) 15.2 4. Total Urban Population (million) 3.9 5. Population Growth Rate (%) 3.2 6. Urban Population Growth Rate (%) 5.7 7. Maternal Mortality Ratio per 100,000 live births 435 8. Infant Mortality Rate per 1,000 live births 76 9. Under five Mortality Rate per 1,000 live births 137 10. Total Fertility Rate 6.7 11. Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (%) 24 12. Supervised Deliveries (%) 42 13. Full Immunization (%) 46 14. Unmet Need for Family Planning (%) 41 15. Stunted Children (%) 38 16. HIV Prevalence Rate (%) 6.4 17. Literacy Rate (%) 69 18. Life Expectancy (years) 50.4 19. Population in Poverty (%)) 31 20. Human Development Index 0.581 21. GDP per capita in 2007 (US $) 370 22. Real GDP Growth Rate 2007/08 (%) 8.9 23. Private investment Growth in 2007/08 (%) 15 24. Public investment Growth in 2007/08 (%) 23 ii TABLE OF CONTENT KeyTU Demographic, Social and Development Indicators 2007 UT ................................................... iiiT ListU of TablesU ........................................................................................................... iv ListU of FiguresU ......................................................................................................... -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

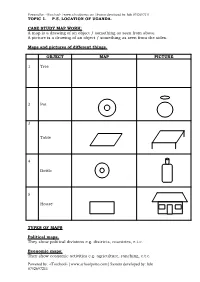

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Detailed Curriculum Vitae Prof. Moses Muhumuza

Curriculum Vitae Assoc. Prof. Moses Muhumuza (PhD)* Bachelor of Science with Education (Biology & Chemistry), Master of Science (Biology)- Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda, and Doctor of Philosophy (Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences)- University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *For correspondence: Email: [email protected], Tel: +256772565565/+256756723711 August 2020 Page 1 of 39 Curriculum vitae- Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza [Bsc. Ed. (Bio.&Chem.)-MUST, Msc. (Bio.)-MUST, PhD (APES)-WITS] SUMMARY OF THE ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza was trained as a graduate teacher by profession specializing in Biology and Chemistry teaching subjects. He eventually advanced his career to focus on Biological Sciences. He has a Masters of Science Degree in Biology specializing in Natural Resource Management, and a PhD in Animal, Plant, and Environmental Sciences focusing on social aspects of rural communities neighboring protected areas in an African context. He also has certificates in project planning and management, project monitoring and evaluation, data analysis and various short course trainings. His expertise stretches across a wider spectrum in both the natural and social sciences. By virtue of teaching at secondary school and university levels, he has engaged in a variety of teaching and research methodologies and accumulated experience in developing self-study materials, writing competitive research proposals and informative research reports. He currently lectures introductory and advanced courses in Biological Sciences, Social science for Conservation, Science education, Climate Change, and Research Methods at Mountains of the Moon University. He has supervised to completion over 30 students’ research projects in sciences and liberal arts both at undergraduate and postgraduate level.