International Conference on Bride Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marriage in the Fiction of Buchi Emecheta Introduction Perhaps

No Woman’s Land: Marriage in the Fiction of Buchi Emecheta Harry Olufunwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Abstract As one of the major ways by which interaction between men and women is regulated in society, marriage has offered a useful yardstick for the assessment of gender relations in many works of African fiction authored by women. The paper examines the way in which the prominent female Nigerian novelist Buchi Emecheta portrays marriage in several novels, including Second-Class Citizen, The Bride Price, The Joys of Motherhood and Double Yoke. Emecheta believes that many of the cultural assumptions which inform marriage gloss over the inherent contradictions that are inherent in its duality as institution and relationship. As institution, marriage ostensibly provides women with the best context within which to fully realise themselves as women; as relationship, the promise of such self-fulfilment is exposed as arbitrary and hypocritical. Many of Emecheta’s principal female characters become aware of this disjunction, and it crystallizes the challenges confronting them as women in a patriarchal society. In this way, she shows how marriage, far from achieving its professed role of affirming the stability of culturally-sanctioned gender relations, actually disrupts them. This paper begins by examining the biological and social drives that underpin marriage, and the way in which they combine to make it an ambivalent condition for women, ostensibly celebrating their femaleness while entrenching their subordination to men. It then focuses on the concept, objectives and process of marriage as these are dramatised by characters and situations in Emecheta’s novels. The paper concludes that Emecheta characterises marriage as essentially indefinable, with unfocused aims and conflicting processes. -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of the Constitution. Preliminary matter. Arrangement of objectives. Arrangement of chapters and schedules. Arrangement of articles. Preamble. National objectives and directive principles of State policy. Chapters. Schedules. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. National Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy. Arrangement of Objectives. Objective General. I. Implementation of objectives. Political objectives. II. Democratic principles. III. National unity and stability. IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity. Protection and promotion of fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms. VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups. VII. Protection of the aged. VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of Government. IX. The right to development. X. Role of the people in development. XI. Role of the State in development. XII. Balanced and equitable development. XIII. Protection of natural resources. Social and economic objectives. XIV. General social and economic objectives. XV. Recognition of the role of women in society. XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities. XVII. Recreation and sports. XVIII. Educational objectives. XIX. Protection of the family. XX. Medical services. XXI. Clean and safe water. 1 XXII. Food security and nutrition. XXIII. Natural disasters. Cultural objectives. XXIV. Cultural objectives. XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage. Accountability. XXVI. Accountability. The environment. XXVII. The environment. Foreign policy objectives. XXVIII. Foreign policy objectives. Duties of a citizen. XXIX. Duties of a citizen. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA, 1995. Arrangement of Chapters and Schedules. Chapter 1. The Constitution. 2. The Republic. -

The Formation of Interpersonal Attraction and Intimate Relationships on Internet Relay Chat

The Formation of Interpersonal Attraction and Intimate Relationships on Internet Relay Chat An Exploratory Study CHERRIE JOY F. BILLEDO This research investigated the formation of interpersonal attraction and intimate relationships on Internet Relay Chat (IRC). Two methods were employed: survey and in-depth interview. Purposive and convenience sampling were used for both methods. Results revealed that the formation of in-person and online interpersonal attraction and intimate relationships have similar initial stages of development. For online relationships however, partners have to undergo processes to shift from online to in-person. It was also shown that similar attraction cues were important online and in-person. A closer examination, however, showed that these attraction cues differ in salience and quality. This study contributes to the understanding of the impact of computer-mediated communication, particularly IRC, on the development of intimate relationships. The advent of computer-mediated communication (CMC) via the Internet, is believed to have significant implications on various aspects of human endeavor. People are not only meeting and interacting through the Internet; they are forming meaningful relationships as well. According to an article in Newsweek magazine, the phenomenon of online relationships is growing at a fast rate that it now warrants serious attention (Stone 2001). In the Philippines, online romantic relationships are already slowly entering the cultural mainstream through Internet Cherrie Joy F. Billedo is an assistant professor at the Department of Psychology, University of the Philippines Diliman. Email: [email protected] Billedo.p65 1 5/26/2009, 11:02 AM 2 PHILIPPINE SOCIAL SCIENCES REVIEW relay chat (IRC), one form of CMC. -

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

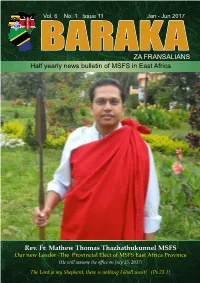

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION

Administrative Report: Uganda Census of 1991 INTRODUCTION The 1991 Population and Housing Census Administrative Report that I now have the pleasure to submit, is the last publication among several reports that mark the completion of the 5th systematic Population Census held in Uganda since 1948 when the first fairly systematic census was carried out. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was the first census in the country to include a fairly detailed survey of the stock and conditions of housing in Uganda. The central concern of this report is to describe in some detail, the trials and tribulations of the administration and management of the 1991 Population and Housing Census. It reveals aspects of successes recorded and problems encountered in the course of managing the three stage activities of the census, namely the pre- enumeration, enumeration and post-enumeration activities. It is our hope that a detailed description of what took place through all these phases will guide future census administrators in this country and help the data users to determine the likely accuracy, of, and strengthen their faith in, the data they are using. The 1991 Population and Housing Census was a result of an agreement between the Government of Uganda and the UNFPA signed in March, 1989 although the idea and negotiations started way back in 1986. For various logistical reasons, the date of enumeration was shifted from August, 1990 to November/December the same year, and finally to January, 1991, which made it close to eleven years from the date of the 1980 census. The census project was funded by the Government of Uganda to the tune of U Shs 2.2 billion and by the UNFPA and UNDP at $5.7 million, DANIDA $ 850,000 and USAID shs. -

The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems

THE HMONG CULTURE: KINSHIP, MARRIAGE & FAMILY SYSTEMS By Teng Moua A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree With a Major in Marriage and Family Therapy Approved: 2 Semester Credits _________________________ Thesis Advisor The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout May 2003 i The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout Menomonie, Wisconsin 54751 ABSTRACT Moua__________________________Teng_____________________(NONE)________ (Writer) (Last Name) (First) (Initial) The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems_____________________ (Title) Marriage & Family Therapy Dr. Charles Barnard May, 2003___51____ (Graduate Major) (Research Advisor) (Month/Year) (No. of Pages) American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual_________________ (Name of Style Manual Used In This Study) The purpose of this study is to describe the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems in the format of narrative from the writer’s experiences, a thorough review of the existing literature written about the Hmong culture in these three (3) categories, and two structural interviews of two Hmong families in the United States. This study only gives a general overview of the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems as they exist for the Hmong people in the United States currently. Therefore, it will not cover all the details and variations regarding the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family which still guide Hmong people around the world. Also, it will not cover the ii whole life course transitions such as childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late adulthood or the aging process or life core issues. This study is divided into two major parts: a review of literature and two interviews of the two selected Hmong families (one traditional & one contemporary) in the Minneapolis-St. -

JAPAN's BATTLE AGAINST HUMAN TRAFFICKING: a VICTIM-ORIENTED SOLUTION When Marcela Loaiza Was Twenty-One, a Stranger Approached

\\jciprod01\productn\J\JLE\50-1\JLE104.txt unknown Seq: 1 22-SEP-17 13:46 NOTE JAPAN’S BATTLE AGAINST HUMAN TRAFFICKING: A VICTIM-ORIENTED SOLUTION JUSTIN STAFFORD* INTRODUCTION When Marcela Loaiza was twenty-one, a stranger approached her in her hometown in Colombia and offered her the opportunity to work as a professional dancer in Japan.1 After Loaiza lost her two jobs due to her daughter’s illness, she accepted the “talent scout’s” offer to provide for her daughter and mother.2 Upon arriving in Japan, three members of the Yakuza mafia received her, promptly took her passport, and informed her that the costs of bringing her to Japan amounted to the equivalent of $50,000.3 For the follow- ing eighteen months, members of the trafficking industry forced her to sell sex on the streets of Tokyo.4 She serviced anywhere from fourteen to twenty clients a day, with a Yakuza pimp always checking how much she earned and keeping her on a strict diet.5 She shared a three-bedroom flat with six other women from vari- ous countries across the world, including Russia, Venezuela, Korea, China, Peru, and Mexico.6 Fortunately, Marcela Loaiza escaped to tell her story, but the same does not hold true for thousands of women who remain under the power of their captors in Japan.7 Compared to their counterparts in similarly situated countries, Japanese authorities * J.D. expected 2018, The George Washington University Law School; B.A. 2008 Chapman University. 1. Anastasia Moloney, “I Had No Idea I’d Been Sex Trafficked”: A Terrifying True Story, SALON (Aug. -

Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1

European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES March 2017 edition Vol.4, No.1 ISSN 1857- 6036 Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1 Charles Quist-Adade, PhD Kwantlen Polytechnic University doi: 10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 Abstract This study sought to investigate the key factors that influence teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in-school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. While the data from the study provided a useful snapshot and a clear picture of sexual and reproductive behaviours of the teenagers surveyed, it did not point to any strong association between parental styles and teens’ sexual reproductive behaviours. Keywords: Parenting styles; parents; youth sexuality; premarital sex; teenage pregnancy; adolescent sexual and reproductive behavior. Introduction This research sought to present a more comprehensive look at teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in- school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. It was hypothesized that a balance of parenting styles is more likely to 1 Acknowledgements: I owe debts of gratitude to Ms. -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala.